Playing in the Moment

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes [and ears].-Marcel Proust

Professor Jon Damian is a guitarist, composer, and educator. He has performed with artists ranging from Brill Frisell to Luciano Pavarotti and Johnny Cash. His book the Guitarists's Guide to Composing and Improvising is available through Berklee Press.

Pardon me for adding to Marcel Proust's words, but his quotation seemed perfect for the ideas I would like to share in this article. Revisiting some basic concepts can be more challenging and illuminating than seasoned musicians might suspect. During my years as a performer and teacher of improvisation, I have noticed that the more advanced we become as improvisers, the less we tend to respond to the basic musical events that happen around us. To make my students aware of this, I started an advanced performance lab class 15 years ago called the Creative Workshop or Cre.W. to help players learn to really listen as they improvise. Although Cre.W. is a guitar lab, the techniques we use work well with any instrumental combination.

Participants don't need advanced sight-reading skills or the ability to shred through a line of chord symbols. The goal is to heighten listening skills and truly play in the moment to compose and improvise original works spontaneously. Inspirational sources for Cre.W. compositions have ranged from the alphabet to the Zodiac, Bach to bop, and jelly beans to doughnuts. For one piece, we even had a goldfish serve as conductor. Guest artists from various media including dance and the visual arts have joined the workshop on particular pieces.

Ensemble members develop their musical communication skills by exploring the basic sound dimensions (dynamics, rhythm, melodic direction, and note articulation). In every playing situation, a greater awareness of these elements strengthens creative potential. The Cre.W. player quickly learns that true improvisation is the ability to be aware of a musical moment and react to it efficiently. Communication is simply taking advantage of your ensemble neighbor's ideas. For this article, I have selected three studies for improving musical communication.

Mime Study

The great French mime Marcel Marceau inspired this study which works with silence. Let's start the mime study by playing an incredibly versatile instrument: the body. By making our bodies instruments, we actually touch and become the music. The body can sing, clap, shout, snap, whine, sniff, stomp, and lots more. It works for an ensemble of two or more players. So your body is your instrument for this first take of the mime study. In example two, we can try using our "regular" instruments.

When I was a youngster, I developed the ability to say the words someone was saying to me as he or she said them! Well, almost (doing this drove folks nuts). Mime study is something like that. First, choose a starting soloist from your ensemble. Soloist one begins to improvise by singing, clapping, whining, etc. Any form of expression is valid. The rest of the ensemble mimes soloist one silently. If the soloist is singing a bluesy lick, the rest of the ensemble mimes it silently with only body motions. Once soloist one finishes, soloist two begins as the rest of the members of the ensemble (including soloist one) mime with their bodies. After cycling through all ensemble members, the group's ESP should be warming up nicely.

Continue with another solo cycle that gradually moves the ensemble from silent reflections of the soloist to actual sound until the entire ensemble is improvising together with sound. For a closing section, gradually move back into silence to complete the first mime study. Once communication levels have increased, try another mime study using your instruments exclusively.

For soloists in the mime study, dynamics, rhythm, direction, and articulation naturally become a part of the music because we are in immediate contact with our bodies. As we clap our hands, we really feel softness or loudness or when singing a bluesy scat, we feel it in our throats. As "silent" ensemble partners in the mime study, we automatically reflect those sound dimensions with our bodies. The mime study is a prelude to improvising a composition as a group. It is also a visually powerful performance piece.

The Coronation

The basic sound dimensions listed above are an integral source of compositional ideas as well as improvisational focal points. In one of the workshop "comprovisations" entitled "The Coronation," we explore melodic direction as a key element in the introduction and the development sections of the improvised piece. The inspiration and overall form are derived from an imaginary coronation scenario. The piece works best with a director and six players: a king and a queen (the featured soloists) and a quartet representing the people of the village who have come to participate in the coronation of their king and queen.

The players are told that the setting is a Seventeenth century castle, so I suggest opening with an improvised Bach-like four-part chorale in E minor. For the first cue, two of the "villagers" listen to each other carefully, improvising slow quarter-note lines in contrary motion. The other two villagers improvise what I call "direction canons" echoing each other. At the second cue, the first pair begins to introduce occasional eighth notes, maintaining movement in contrary motion. Soon the second pair introduces eighth notes in their canon.

Cue three signals the entrance of the king and a modulation to E major. Under the themes of the king and queen, the villagers play with muted strings. The king performs an aria and is joined by the queen in a duet. At a point of climax, the villagers stop muting their strings and everyone imitates a tympani roll by playing a tremolo.

A cut off by the director cues the development section. The first pair of villagers begins to play a double-time duet, keeping a sixteenth-note feel throughout and maintaining their direction roles. When they finish, the second pair does the same thing. At the conclusion of their duet, both duos improvise together.

For the recapitulation, the villagers once again mute their strings as the king recaps his theme and duet with the queen. At the climax, the villagers stop muting their strings and play the tremolo tympani roll until the director cuts everyone off. For the recessional, the villagers once again play quarter-note lines in E minor and the piece fades out. To hear how one Cre.W.

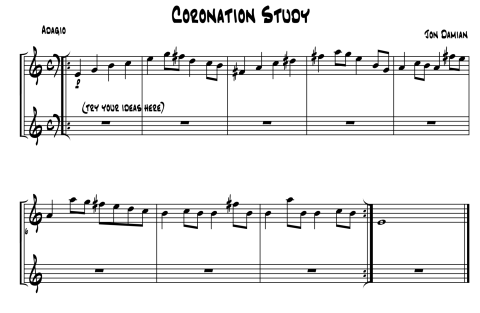

In order to practice these approaches on your own before trying them with other instrumentalists, I have included two direction studies (they are also posted online). The first is a simple E-minor line. Listen and improvise along with it moving in contrary motion to the line either above or below it with any rhythms you choose. If you want, sketch in a line moving in contrary motion, then play your idea against the track. Also try improvising or sketching some direction canons against the track.

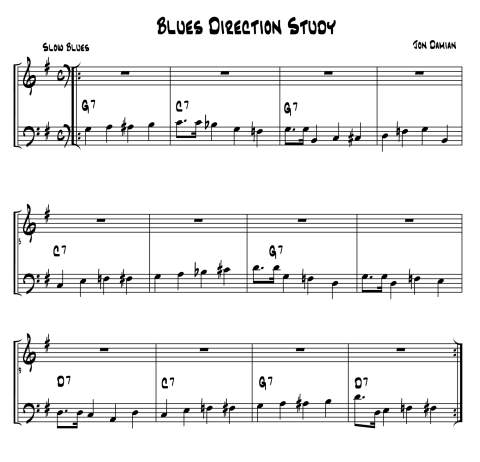

The same can be done in the Blues Direction Study in G. Try direction ideas inspired from the bass line and with rhythmic freedom. Notice how in each of these direction studies, contrary motion creates a powerful depth and independence between the voices.

EX.1

EX.2

In Conclusion

Focusing our improvisations on the basic sound dimensions rather than only on complex harmonic structures and rhythmic phrasing enhances our creative potential in any performance situation. Training yourself to listen and react will bring you into the moment in your solos, heighten your awareness of what the other players are doing, and make the music more cohesive.

As mentioned earlier, one Cre.W. composition called for a goldfish to serve as the conductor. Incidentally, that goldfish died a week before the concert. I am happy to report, though, that his understudy did a great job.