It's All About the Song

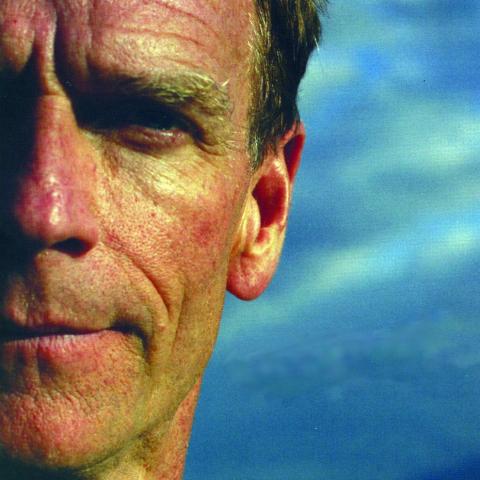

Livingston Taylor

Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.” But such a lack of inspiration isn’t an issue for Livingston Taylor, a professor in the Voice Department. On his new CD, There You Are Again, he presents a collection of masterfully crafted songs that are rich, meaningful, and stylistically quite diverse. As a vocalist, Taylor gives the performance of a lifetime, holding his own alongside a superstar cast that includes his brother James Taylor, Take 6, Vince Gill, Carly Simon, and Andrae Crouch. The disc’s 12 songs feature brilliant arrangements performed by a stable of instrumentalists, such as Steve Gadd, Leland Sklar, Matt Rollings, Jimmy Vivino, Dan Dugmore, David Sanborn, Gary Burton, and Jeffrey Mironov, as well as a lengthy list of string and horn players and backup singers. For more on the new CD, visit Taylor’s website at www.livtaylor.com.

Having a talent pool like the one that Taylor enlisted will get you pretty far along the path to making great music. But to go the rest of the way, it’s all about the songs. They’re the heart of any great pop album, and this is where Taylor’s latest effort really shines. He tackles an array of emotions that run the gamut, from the exhilaration of spiritual redemption to the sweetness of enduring love to candid self-assessment. The songs offer the observations of a man who has thought a lot about life, and they nudge listeners to reflect on their own lives. Recently I sat down with Taylor to discuss his songwriting process.

Do you believe that the best songs come from an initial spark of inspiration?

Sometimes there is a creative spark that leads to a great song, but many can write very well on assignment. You don’t necessarily have to wait for the manna from heaven to make it work. Sometimes those sparks turn out to be junk, and sometimes the methodical approach turns out really well. When a songwriting team like Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein needs to write music for a play, great music comes out.

I’ve always found it suspect when somebody says they wrote a great song in a half-hour. Sometimes great things are written that way—I’ve even written good songs that way. But generally my songs take months to write. In some instances, it’s taken me years to solve lyric or plotline problems I might be having with a song. So as a rule, it generally takes a long time to write a good song. You need a melody that’s compelling and interesting enough so that you’ll be willing to continue working on it despite the fact that it’s taking so long. Sometimes a writer will do a lot of work conceptually beforehand, and then the song itself seems to just come out of nowhere. The fact remains, though, that a lot of work was done before the song came about.

What comes first when you write, the lyrics or the melody?

I like writing a lyric to a melody. Sometimes I’ll write a melody to a lyric, but generally those melodies tend not to be very interesting. I love to start with a melody and then fill in the lyrics. Sometimes a melody may come very quickly. I was working on a song titled “Call Me Carolina,” and I rewrote the thing three times. I had the melody but wasn’t able to get the lyric to fit in. It’s done now, but it was a lot of work. To get to the point where a song is finished, you may make some compromises. You listen hard as you sing it; and if it doesn’t grate on you, it’s finished.

What kinds of compromises are you talking about ?

When you’re singing the song and you get to a section that might be weaker than the others, that’s the place where you really sharpen up and sing it loud and true. What you’re saying is, “Listen, I know the lyrics in the last half of this verse aren’t as strong as those in the chorus, but I don’t care. It’s the compromise I made, and I’m going to stand by it.” The good parts don’t need any defense, but you need to defend your compromises. It’s fine for someone to challenge me on them if they must, but I’m very clear. I know there are compromises, and I made them because I had to. The idea that it’s our compromises that need defending really freed me.

The lyric that allowed me to conceptualize this notion comes from Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” It’s in the verse that says: “From the mountains, to the prairies / To the oceans white with foam.” If Berlin were here, he might disagree with me, but I don’t think that foam is a great word choice. But he needed a word to rhyme with the line “God bless America, my home, sweet home.” That line was bomb-proof; he couldn’t change it, so he needed a word to rhyme with home. What else could he say: “To the gardens filled with loam”? We’ve become used to the song, but I believe that word was a compromise. Irving stood by it and probably would have vigorously defended it. I can imagine some record producer in 1938 saying, “I like the song, but what about that word foam?” I think Berlin would have said, “Have you got a better lyric?”

Throughout the making of my record, when my producer would say he didn’t like a lyric, I’d say, “That’s fine, but you need to give the compelling reason why I should change it.” If you don’t like it and I do, as the songwriter, my feeling trumps yours unless you can give me a well-reasoned argument. When someone makes a good argument to me—and that happened on this record—I’ll make a change.

Are you encountering great young writers coming up through the ranks?

In my classes, I have four students that are wonderful songwriters. I’m impressed with the caliber of their material. I hope writers like that will lift up the music industry. I hear some compelling lyrics from my students. But there is a difference between being a writer who is 21 and a writer who is a fully mature and capable lyricist. We have seen some anomalies like Laura Nyro, who came along writing unbelievable songs at 16 or 17. Generally, the best song and lyric writers are the product of a lifetime of hard work and study.

In your estimation, what are the serious issues facing contemporary songwriters ?

One of the difficulties that songwriters face is that the video images that go along with a song have discouraged the creation of focused lyric content. The more obtuse a lyric is, the more adaptable the video can be. A video can then complete the message of the song. The problem is that when you take away the video, not much is left.

Our real challenge in a world where everything can be transferred instantaneously with no effort is figuring out how to generate a revenue stream that will protect songwriters and reward competence. You need a concentration of finances that will enable people to assemble great forces—musical, lyrical, and production forces—to make great music and get paid for it. If you can’t generate money from it, you won’t be able to assemble great people. The greats will do something else; creative people can go anywhere. If we can’t attract them to music, they’ll go someplace else.