California Dream Studios

After clocking thousands of hours in recording studios as an in-demand film composer and session musician, Richard Gibbs '77 had a vision for his own studio. "I'd been in so many studios around the world that I had a pretty strong opinion about how my dream studio would operate," he says. "I wanted everything that makes it look like a studio hidden. This place can pass for a beautiful living room but has full functionality as a studio."

Gibbs's overriding objective for the residential studio built on his 1.5-acre lot next to his home was to construct an aesthetically appealing studio that would inspire musical creation and equip it with bleeding-edge technology to capture the results of that creative process.

In 2005, after spending two years obtaining the necessary permits from the city of Malibu, California, and resolving design-, technology-, and construction-related considerations, Gibbs opened the doors of Woodshed Recording. Together with architect Akai Yang, studio design consultant Jack Viera, and builder Kevin Beck, Gibbs created an American Craftsman-style building whose dozen French doors offer inspiring vistas of wooded valleys and the Pacific Ocean, along the Malibu, Palos Verdes, and Santa Monica coastlines in the distance.

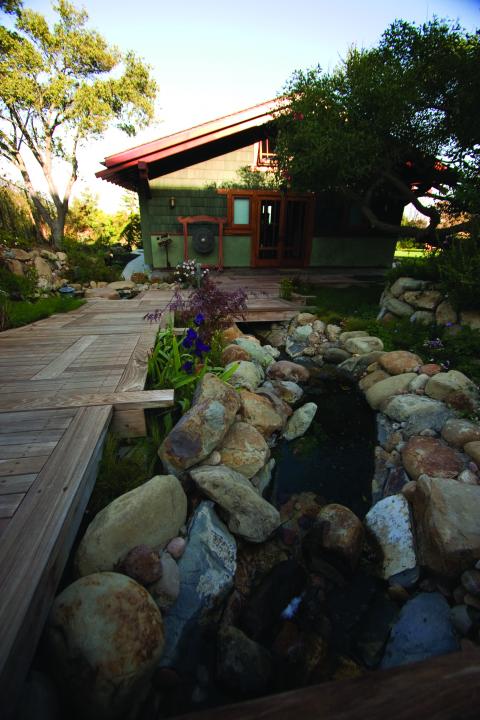

The main room at Woodshed Recording features a comfortable living room environment. The pastoral setting of the studio includes a bubbling brook and koi fish pond. A machine room in the basement houses the recording gear.

To create a homey environment, Gibbs chose mahogany floors, doors, and windows, and exposed Douglas fir beams and rafters overhead. A keyboardist and guitarist, Gibbs keeps an array of instruments (including a Yamaha grand piano, a Hammond B3 organ, and a vintage Fender Rhodes suitcase model electric piano) and sundry percussion instruments in plain sight.

Among the studio's hidden features are a floated slab floor in the main room and an arsenal of outboard gear and computers running the latest version of Pro Tools in a machine room on the basement level. All gear can be accessed remotely. The layout offers several options for soundproof isolation booths. Two in the basement house a Leslie organ speaker and a Bogner guitar cabinet. The main floor features mic jacks in the tiled bathroom, wood-paneled office, and upstairs sleeping loft, offering other isolated spaces for recording.

Moveable wall panels seated in floor tracks allow Gibbs to arrange larger soundproof spaces in several configurations. Musicians recording there can create a drum shack or vary the size of the control room and main stage depending on the needs of the session. (Gibbs has comfortably seated a 30-piece orchestra in the room for a recent scoring session.) The board is mounted on casters and is easily moved. All wiring is in pits under the floorboards allowing the board to be cabled up in a choice of three locations around the room.

"I've realized in retrospect that musicians going into most studios are in actuality the guests of the engineer," Gibbs says. "It's their realm, not the musician's. When engineers come here, it's my realm. That gives the sessions here a different feel. The musicians are immediately comfortable and it's the engineers that have to adapt — and they do."

The pastoral setting of the studio includes a bubbling brook and koi fish pond.

Having a quiet environment was paramount for Gibbs. "I can't stand background noise," he says. "I've been astonished at how much ambient noise I find in many professional studios — especially in the control room. I hear hard drives spinning, computers humming, and fans whirring, never mind technical problems that add noise."

Gibbs built the studio as a place to create his own music for film and TV projects and to produce artists. About 80 percent of the time Gibbs is the studio's main occupant, but when his calendar is clear, he rents the studio to established artists seeking a unique work environment.

"Sting and his engineer were here for a month when Sting was writing his musical," Gibbs told me as we sat on the studio's porch in a gentle sea breeze. "Pink wanted to record two additional songs for her greatest-hits album and chose to do them here. Like Sting, she has a house in this neighborhood and didn't need a place to stay. But she'd brought in a production crew from Sweden and they needed accommodations. Since our kids are out of college living on their own, I just rented out the whole property. My wife and I left for two weeks and went surfing in Indonesia."

Surfing is Gibbs's second passion after music. He was born in Ohio but grew up in Daytona Beach, Florida, where he started surfing. From there, he left to attend Berklee during the early 1970s and pursued a degree in composition. After graduating in 1977, he returned to Florida, packed up his surfboards and keyboards, and drove to Los Angeles. He was looking to break in as a composer or session player or maybe to join a successful rock band. All three opportunities ultimately came his way.

Sessions, stage, and screen

A serendipitous meeting with Chaka Khan's bass-playing kid brother Mark led to Gibbs's first professional gig in Los Angeles. He penned horn charts and served as a keyboardist and music director for a short tour with the renowned r&b singer. In 1980, Gibbs joined Danny Elfman's new-wave band Oingo Boingo and toured and recorded with the group for four years. "Boingo helped my reputation as a session player," Gibbs says. "I got calls for sessions even while I was on the road. People would fly me in to studios in Canada or L.A. on our days off." To date, Gibbs has played on 150 albums with top acts, from Aretha Franklin to Boy Meets Girl to Tom Waits.

After leaving Oingo Boingo in 1984, Gibbs continued doing sessions for movies, TV, and albums. An engineer friend recommended him as an arranger and composer for his first movie, Sweetheart's Dance, in 1988. That opened doors for a gig as the musical director for the Tracy Ullman Show and work on subsequent Ullman projects. That connection led to Gibbs being hired to compose the music for the first season of The Simpsons. "After that my career as a composer took off," Gibbs says. "The agent representing Danny Elfman for film work took me on. Danny's career was taking off like a rocket, and I was seen as someone who could handle the gigs Danny couldn't take."

Richard Gibbs built the Woodshed first and foremost as a creative environment.

Since the late 1980s, Gibbs has scored numerous TV shows and more than 50 films including Dr. Dolittle, Say Anything, Cleaner, and Judy Moody andThe Not Bummer Summer, to name a few. His collaboration on songs for the movie Queen of the Damned with singer Jonathan Davis of Korn was recorded at Woodshed and yielded a Gold record.

One would be hard-pressed to name another studio with a setting comparable to that of Woodshed Recording. Before construction began, Gibbs consulted conventional studio designers, who told him that the glass in the French doors would create acoustic problems. But there was no way that Gibbs was willing to hide the inspiring panorama with soundproofed walls. Viera rightly informed him that pairs of windowpanes of different thicknesses with no space between them would resonate at different frequencies, avoiding the problem and preserving the view. "So far I've only encountered one problem with this setup," Gibbs says with a wry smile. "When I recorded the orchestra here, the violinists kept getting distracted. They're not used to working with a view like this."

To see photo galleries and videos of the studio, visit www.woodshedrecording.com.

Levels' Playing Field

Brian Riordan '94 founded Levels Audio, one of Hollywood's busiest post-production audio studios.

Mix 1, the flagship mixing room at Levels Audio

After graduating from Berklee, Brian Riordan arrived in Los Angeles hopeful that his songwriting and composing skills would gain him a toehold in the music business. But it turned out that his tech skills opened the door to his career.

And over the past two decades, Riordan has built an impressive résumé doing postproduction audio for TV and movies and a multimillion-dollar, 13,000-square-foot studio complex on Highland Avenue in the heart of Hollywood's Media District. At Levels Audio, Riordan and his staff of 17 full-timers and a few freelancers offer a range of services, including music editing, mixing, sound design, automated dialog replacement (ADR) and Foley recording, visualFX, and more for reality shows, award shows, live-music shows, documentaries, and episodic TV programming. Work by Riordan's team has netted several awards, including three prime-time Emmys.

Brian Riordan ’94

Along the way, Riordan has discovered that, in addition to his formidable tech and music skills, he has a keen business sense. He has expanded his business despite two Screen Actors Guild (SAG) strikes, the general disturbance of commerce following 9/11, the current economic downturn, and the slashing of TV budgets. He's also learned to avoid being consumed by an industry where punishing deadlines are a cost of doing business.

Prior to attending Berklee as a professional music major, Riordan lived in Wisconsin. He'd played piano and guitar as a kid, but focused his studies on songwriting, composition, and arranging courses. Concurrently he developed an aptitude for technology but never took MP&E courses at Berklee.

"My friends called me 'the MIDI guru,'" Riordan says. "I was teaching myself about recording and sequencing using Digidesign and early versions of Pro Tools in my freshman year. I also had a job at Daddy's Junky Music and earned points from equipment manufacturers for selling their equipment. I could cash those in for gear, and by my junior year in college I had a pretty good home studio."

Riordan headed to Los Angeles after graduation and took a job as a production assistant for Roseanne Barr working on a short-lived comedy show calledSaturday Night Special and on other projects. "I was putting in 18-hour days for about 75 bucks a day," he recalls. "I was doing all kinds of things. But after about six weeks, I realized that this wasn't exactly where I wanted to be. I was working too many hours and not making the money, and I didn't really want to end up being a TV producer. It wasn't my passion."

Seeking a Studio Tan

He turned to the recording studios and worked first as a mixer, then recording voice-overs for video games at a small studio north of Los Angeles in Reseda. "I worked for them for probably six months and really got my Pro Tools chops up. But I was continually networking and found a job at a company called Hollywood Recording Services. At their facility on Sunset Boulevard, they were doing a lot of big commercials. In a short period of time, both of the studio owners died, and one of the wives became my boss. She was an accountant trying to run the business, but she didn't really know how to run a studio. Even though the environment was unstable, it allowed me to really excel at doing voice-overs, mixing, and sound design. I ended up cultivating a large clientele doing a lot of big commercials."

Riordan stayed there for a handful of years before starting his own business, Levels Audio. "In 1999 I jumped ship and started my own studio with a partner-a film composer who became my financial backer. I brought most of my old ad clients with me and started out working by myself in a one-room facility."

When the Screen Actors Guild strike of 2000 crippled the advertising industry, Riordan's contacts helped him get work on Disney animated shows such asHercules and Toy Story and music remixing for awards shows.

First-floor lounge and reception area at Levels Audio

"That's when I realized I should be doing music for television," Riordan says. "My love is music, but television was where the stability was. My buddies working in the music business were all hopping from label to label and getting canned, and friends that were mixing worked crazy hours in the studios until four in the morning."

But Riordan's schedule wasn't exactly leisurely; he was working seven days a week to build the Levels Audio brand. "I'd never worked so hard in my life," he says, "because I didn't want to turn away business."

Idol Hours

As the first season of American Idol was ending, the producers called Riordan to get help in cleaning up the two-hour concert finale featuring all 32 contestants. The show was becoming a raging success and Riordan knew the stakes were high.

"They brought me in at the very end and told me that if I did the job well, I'd get the series. But that was the hardest gig I'd ever done to date. The music was a total train wreck, and the show was scheduled to air the next week. I worked on it by myself for 59 hours straight without sleep, pitch correcting and tuning vocals for every performance. It was a huge job, but I knew what was riding on it, so I toughed it out. In the end, it sounded pretty good."

The people at Fox concurred and gave Riordan the series. He built a second room in his building and hired Connor Moore, an engineer who had been working for The Bachelor, and brought that show with him to Levels. Having these shows as Levels Audio clients enabled Riordan to add more reality programs to his company's roster.

As Riordan attracted new clients, he needed more employees and more mix rooms and decided to build a large, state-of-the-art audio complex. "I was looking for another space, and found this building," he says. "I was able to raise the capital between banks and private lenders, bought the building and gutted it."

He selected architect Peter Grueneisen to help him create a top-shelf postproduction facility. "We built the rooms the old way with floated floors with compression ceilings," Riordan says. "Everyone was telling me that no one does it that way anymore. But I plan on being here a long time, and I wanted to do it one time and do it right. We charge a premium for our services and if I'm going to do that, I want to give clients what they deserve."

Construction took nearly two years and was completed in 2006. Within a year of opening, Riordan had all his mix rooms booked five days a week. Levels has 5.1 surround sound rooms for mixing, edit bays, a guest loft, conference room, and more. "We have seven mix stages and an ADR/Foley stage here," Riordan says. "We also have the editorial rooms where guys are cutting dialogue, sound effects, and music, plus a machine room staffed with guys doing the technical and IT stuff. We've also got a room at a video editorial company across the street and another mix room over there. So we have eight mix rooms total right now. I believe that makes us the largest independent postproduction facility in Los Angeles."

Riordan's clients were immediately impressed with the new building and the work Levels was turning out. The company website features a handful of testimonials, including one from American Idol's Ryan Seacrest (see www.levelsaudio.com). "In addition to being one of the most comfortable settings in the country to record, the studios are completely state of the art," Seacrest says. "The experience was nothing short of perfect."

As they enter, visitors first encounter the spacious first-floor lounge with brick-and-concrete walls adorned with wood slats and an open ceiling with a variety of lighting sources including skylights. It has an industrial yet inviting ambience. Riordan describes his operation as a boutique, owner-operated business that is service-oriented. In addition to cultivating new accounts and managing the business, he still puts in time behind the board and says he'll never stop mixing.

"We've got a well-oiled machine here," he says. "I no longer have to do everything myself. I've learned to delegate and understand the strength of a team." Riordan has assembled a dedicated staff and cultivated a feeling of family among them. This helps when schedules get intense and Levels is operating day-and-night shifts. The first quarter of the year and the summers are particularly hectic in Riordan's industry. During the summer, major artists are touring, and Levels edits a lot of televised concerts. Between the major networks and the multitude of cable channels, summer is also a busy time for reality shows. Riordan has learned to keep up the pace but not get crushed by the workload. "In the last three years, I've really put all of my focus into life balance," he says. "We've grown the business enough to hire more people to handle volume by spreading things around.

"If you surround yourself with talented people and mentor new young talent, you end up with a really amazing team. This place is all about the team that works here. The facility is great, the equipment's great, and we have nice parking for Hollywood. But you could take all of that away, and we would still be able to work somehow. We could find new equipment, but the team is not replaceable."