Out of Africa

Lionel Loueke

Jimmy Katz

The musical path of guitarist Lionel Loueke as been quite different from that of most jazz musicians. Loueke’s journey began in the tiny country of Benin in West Africa and, after many unforeseen twists and turns, has taken him to some of the world’s most prestigious concert venues. As a member of the sextet led by renowned pianist Herbie Hancock, he recently completed a European tour and touched down in Berlin, London, Warsaw, Milan, Stockholm, Athens, and elsewhere.

I caught their show at Symphony Hall in Birmingham, England. Hancock’s introduction of Loueke to the audience made it clear that Hancock is excited about what Loueke brings to his music. During the set, Loueke swayed as he played unison lines with Hancock and trumpeter Terence Blanchard, produced ambient chordal swells, a range of electronic and naturally produced effects, funky chord jabs, and wordless vocals behind his guitar solos on such Hancock chestnuts as “Speak Like a Child,” “Chameleon,” and “Actual Proof,” as well as Loueke’s “Seven Teens” and Wayne Shorter’s “V.”

As an amalgam of African, European, and American influences, Loueke’s style has prompted critics to proclaim him one of the most original jazz guitarists to emerge in years. Growing up in Cotonou, Benin, Loueke spoke Fon (native to southern Benin), and French (Benin was a French colony until gaining independence in 1960). Loueke was exposed to traditional African music that included strains of samba played in nearby Ouidah (his mother’s home city), an artifact of the Portuguese influence on the area. After picking up the guitar at 17, he sang and played percussion for traditional ceremonial events and began playing Afro-pop. But when he heard George Benson’s Weekend in L.A. album, brought by a family friend from Paris, Loueke’s passion for jazz was ignited. Benson’s fleet-fingered improvisations and scat singing were a revelation, and Loueke learned them note for note. Seeking instruction on improvisation and harmony, he entered the National Institute of Art in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, where he learned classical music theory, but not jazz. In 1994 he left Africa for Paris to study at the American School of Modern Music, an institution founded by Berklee alumni that is part of the Berklee International Network.

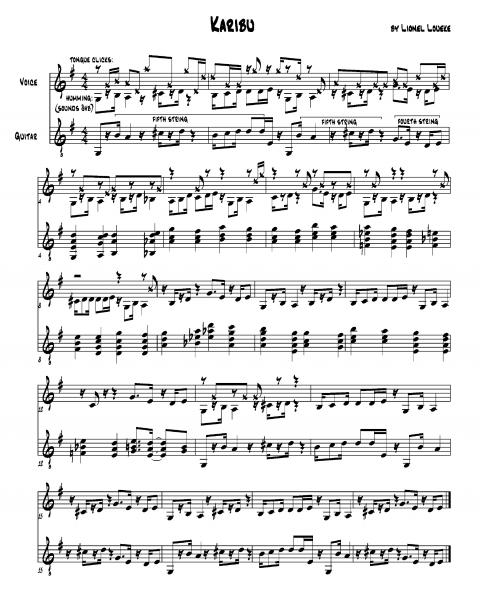

At the American School, Loueke got his first instruction in jazz, and Paris afforded him easy access to instructional books, CDs, and guitar strings, resources that were nearly impossible for him to find in Africa. For Loueke, who once had to use a bicycle cable to replace a broken guitar string, the opportunity was huge. After finishing his studies, Loueke received a scholarship to complete his diploma at Berklee. Arriving in Boston in 1999, he received his first private instruction in jazz guitar and met Italian bassist Massimo Biolcati ’99 and Hungarian drummer Ferenc Nemeth ’00, among others, at Berklee jam sessions. In 2001 he earned his Berklee diploma, and later that year, Biolcati, Nemeth, and Loueke were chosen to attend the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz in Los Angeles. The three continue to tour and record as the Gilfema Trio and can be heard on the group’s eponymous album from 2005 and Loueke’s 2008 Blue Note Records debut recording, Karibu.

Loueke’s three years at the Monk Institute yielded important educational opportunities and professional connections that bore fruit immediately. Faculty member Terence Blanchard took Loueke under his wing and featured him in live shows, on his Flow and Bounce CDs, and on his Inside Man soundtrack. In 2005, Hancock hired Loueke for live dates and to record on his star-studded Possibilities CD, his Grammy-winning CD The Joni Letters, and others. Loueke reciprocated by inviting Hancock to play with him on his Virgin Forest and Karibu CDs.

Today, Loueke’s career is in high gear. He has done five CDs as a leader and been a sideman on 24 others with an array of artists, including fellow Benin native Angélique Kidjo. These days Loueke lives with his wife, son, and daughter in New York, but he has deep roots in the soil of African culture and tradition. In an effort to help African musicians and give back to Berklee, Loueke serves on the college’s Africa Scholars Program Advisory Board, giving input on the scholarships awarded to young African musicians. As for the future direction of Loueke’s musical path, anything is possible. He says he may make an album of standards—played, of course, as only he could.

Was it hard for you to become a musician growing up in Benin?

I have to say, it was tough. I knew when I was very young that I wanted to be a musician, but I had to wait until I was 17 before I even tried to play guitar. As for learning about music in Benin, it was hard to find material. Back then there were no music stores and no library. It was difficult to get information; it was hard to just to find guitar strings.

Were there instruments around the house for you to learn on?

My brother had a guitar, but I wasn’t allowed to touch it. I would play it when he wasn’t home. One day he caught me, and I thought he would slap me, but he didn’t. He said, “Oh, you want to learn? I’ll show you.” Once, when I went back home, I gave him a Yamaha electro-acoustic guitar. But he’s not playing it; he’s too busy.

Do radio stations in Benin play your music?

There’s a weekly jazz show on the radio that has played my tunes. Every time I go back, I always go to the station and talk. There’s not a big jazz community, but it’s growing. I go home once each year and play a concert at the French Cultural Center. Eight or 10 years ago, we started with about 75 people. Now we have 500 people coming out.

At these concerts, do you play as a solo artist, or do you bring a band?

Sometimes I play solo, and sometimes I play with local musicians. The way I play back home is always different, because I try to bring the people into the music with something they already know: traditional songs and other stuff. But I play the songs in a way that is different from the way they usually hear them.

In the beginning, you were self-taught. What led you to the National Institute of Art to study classical music?

The reason I went to Abidjan, Ivory Coast, was because it was the only place I could study music. I didn’t really care what music I studied. I ended up at a classical school, but I wasn’t into classical. It was important for me to know how to write, who Beethoven was, and to be able to analyze a piece. I was there for three years. I didn’t take any classical guitar lessons, but I studied composition and theory.

From there you went to the American School in Paris.

I wanted to go the Occident, either Europe or America. America was my first choice, but I didn’t go there because of the language barrier. I didn’t speak any English then, just Fon and French.

The American School in Paris was the first real jazz school I ever went to. I felt like a kid in a candy store, because there were so many CDs and other things available there. I bought a machine called a reformatique for transcribing music. It slowed down the speed of music on CDs without changing the pitch. Back home I used to use a cassette player with dying batteries, but that would slow everything down, including the pitch. I learned a lot by transcribing and memorizing things. I didn’t write anything down. I started with guitar music and then moved slowly into transcribing saxophone and piano, but I mostly did guitar music.

When you came to Berklee, did certain teachers have an impact on you?

Berklee was the first place where I had a private guitar teacher, Mick Goodrick. It’s hard to get him in your first semester. I talked to him, but [initially] he didn’t take me, I guess everybody wants him. Then I played at one of the Guitar Night concerts, and he was there. I went to see him again, and he said he’d take me. I wish I could study with him now, because I feel more ready. I also studied with Jon Damian and Rick Peckham. I had other great teachers there, like George Garzone. I never had a chance to study with Hal Crook at Berklee, but I did when I was at the Monk Institute.

After I finished Berklee, I stayed in Boston for a few months. My friend Massimo Biolcati called me to play a session with Hal Crook. After the session, Hal asked me if I’d heard about the Monk Institute, and I said no. He told me it was a program where you study with the best musicians and get a little money to live on. I said I didn’t want to go back to school anymore after studying in Abidjan, Paris, and Berklee, I just wanted to go out and play. Hal said I should check it out. So I did. The deadline for applications was the next Monday, so I got my materials in.

Weren’t your Berklee friends Massimo Biolcati and Ferenc Nemeth accepted that year too?

Yeah. It’s funny because Massimo played on my audition tape, and I played on his.

Did trumpeter Terence Blanchard listen to the tapes to pick the students?

Herbie Hancock listened to my tape, but I don’t know why. A teacher from USC [the University of Southern California] was to listen to the guitar players. He picked four or five, but he did not pick me. Herbie saw the list, and asked, “What about the guitar player I heard?” The teacher said, “Yeah, he’s good, but he’s not that strong rhythmically.” Herbie said, “No, you gotta be kidding me.” Herbie was the one who saved me.

At the Monk Institute, what did you focus on?

There wasn’t any instruction on chord scales or things like that. It was more about how to develop your own voice and personality, the music business, and what to do after you left the school. It was more about what you don’t learn in music school that most have to learn on the road. Having people like Herbie, Wayne Shorter, Terence Blanchard, and Kenny Barron teaching us was perfect. They told us how to get out there and not to be afraid to try different things.

Since Terence hired you play with him early on, you got out there right away.

I was playing with him before the program was over. I spent three years at the Monk Institute, and during the second year, I started playing with Terence. I couldn’t do every gig because of school, so I was playing mostly weekends with him.

You played percussion before you picked up the guitar and became aware of harmony later. That must have represented a whole new world for you.

It took me a while to see that I could use all the rhythms I grew up with in a harmonic context. I keep practicing and learning, trying to get everything to work the way I hear it.

In terms of harmony, you jumped into the deep end of the pool when you started playing with Herbie Hancock and Wayne Shorter.

Oh man, I know. Playing with Herbie every night and hearing his voicings has changed my approach to my instrument. I don’t think of the guitar the same way, especially when I play in trios where there’s a lot of harmony to work with. My concept is getting closer to piano. I comp for myself as I play lines.

Some of the music you played last night was a mixture of tunes with complex chord progressions and open vamps.

Some of the tunes, like “Actual Proof” and “Speak Like a Child,” have difficult chord progressions. Others sometimes sound like there are no chords. We played my tune “Seven Teens,” and it’s just a vamp. It can be whatever you want it to be. One of my favorite parts of the show is Herbie’s piano solo. It’s completely different every time. Hearing him build his solo from scratch each night is a great learning experience for me.

You played some things that were atmospheric and textural, some lines with the bass, others with the piano, as well as singing and comping. Your approach to his music is quite varied.

I try to hear what I can do and where I can fit in. It’s always a decision I make in the moment, not before or after. Once I feel it, I have to play it. When I don’t feel it, I just leave space. It’s a challenge. Herbie knows how hard it is for both piano and guitar to play harmony at the same time. I love doing that with him because he gives me room, some space to grab. He’s always suggesting stuff. My comping is getting better just by listening to him and seeing what I can do to help the music and the musicians sound better. If I feel like I’m getting in somebody’s way or there’s no need for me to play, I’ll stop.

You get many different sounds and textures from your guitar from electronic effects and natural effects produced by tapping, or putting paper in between the guitar strings. Did you start doing the natural effects in Benin?

No, actually, I started doing that when I was in Paris. I remember being in my studio trying to find something to keep me excited about the instrument. I started using paper, combs, and plastic bags to make different sounds. Paper works best. Every time I use the paper, it affects the way I play, and I start hearing other stuff.

With the electric instrument and guitar synthesizer there are so many ways to go now. I like the natural acoustic sound of the guitar, but I also like the technology. I take months to learn to use the technology in the right way because it can be too much—a gimmick—if you aren’t careful.

I’d heard that you don’t use a pick and play with your fingers almost exclusively. But last night you played with a pick quite a bit. Do you like to mix it up?

I still play a lot with a pick, especially when I play on steel strings. Also, I feel Herbie’s music needs electric guitar more than acoustic, especially on the funk stuff, and I need a pick for that. But when I play a solo, it doesn’t matter if I’m on the electric or acoustic, I always play with my fingers.

After the people at Blue Note records heard your work on Terence Blanchard’s Bounce and Flow albums, did they decide to sign you?

Actually, Bruce Lundvall [the president of EMI Music, Jazz and Classics, U.S.] heard me in Toronto on the second or third gig I played with Terence. He said, “Man, I would love to hear what you would do on your own.” He couldn’t find his business card, so [producer] Michael Cuscuna gave me his card, and I sent them my demo. I didn’t hear back for a few years. I moved to New York in 2003 and I saw them twice, but nothing. I didn’t want to push it; I figured maybe they didn’t like the demo. Then in 2005 or 2006, I received a phone call [from Blue Note]. I heard later on from Terence that Bruce wanted to sign me right away, but somebody told him he should wait until I got more experience with Terence. I guess that’s what happened.

On his Flow CD, Terence gave you lots of room to express yourself.

Oh yeah, plenty of room for my playing and compositions—everything. I’m very lucky. Terence has been great to me as a person, and he’s a great bandleader.

Did Blue Note give you direction for the type of music it wanted on Karibu?

No. That’s what I love about the label. As a young artist, I expected that they would tell me what to do. But they didn’t, which was perfect, because I didn’t want to do something I didn’t feel. We didn’t really talk about it. They asked me what I wanted to do, I said I would love to have Herbie and Wayne play, and they said great.

Was your tune “Light and Dark” written with Herbie’s style in mind?

I wrote three sections with Herbie and Wayne both in mind, but I didn’t want to sound like I took one solo, Herbie another, and then Wayne. I wanted a piece where we soloed from the beginning, and you don’t even hear the head that much. I’m the only one playing the head. It ended up by being the longest take on the album.

Do you have ideas about what you’ll do on your next Blue Note album?

I feel like I’m going naturally in the direction of longer, improvised pieces with my writing. The new ones may not be as extended as “Light and Dark.” The African elements and the voice will always be there, but harmonically I’m going a bit deeper.

Sometimes you sing with lyrics, and other times you use wordless vocals, which has prompted some to categorize you as a world-music artist. How would you prefer to be known?

Personally, I feel like I’m more of a jazz artist with some different talents. There are jazz players from Cuba and elsewhere who bring their own influences to the music. I approach the music with a jazz attitude; everything is based on improvisation. Even the tunes I sing are never the same, because I’d get bored just doing the same thing. I don’t know what people consider world music to be. It’s a big category. I’m just a musician trying to find my way, and I’m definitely in deep on the improvisation side. So call it jazz.

Is improvisation the link between traditional African music and jazz for you?

African musicians improvise all the time, from the percussionists to the singers. That’s what I think of as jazz. It’s not only about the harmony; it’s the way you approach the music. To me, the griots in Africa are jazz musicians because they improvise all the time to announce the king.

It must feel great for you to be touring with an artist as established as Herbie and being introduced to his audience.

Every night he gives me a spot to improvise, to just play something by myself. He trusts what I’m doing, and he is helping me just as he was helped by Miles. Herbie has done so many styles, tangents of jazz, that different generations love him for different CDs. The show we did last night had everything from “Chameleon” that most people want to hear to “Actual Proof and “Speak Like a Child.” He always finds a way to bring everybody in. You may not like every piece, but there will probably be songs you’re going to like no matter what.

In the future, do you see yourself as an artist who, like Herbie, goes through different style periods?

I think so. As I said, I get bored doing the same thing. I need something that keeps me excited and takes me to a zone where I don’t really know what’s going to happen. Herbie and Miles have always been true to the music, no matter what style they were playing. I don’t know what I’ll be doing a few years from now, but I know for sure it’s going to be different. For the music to keep growing, we need to be growing too. I’ve been writing a lot lately. I’m mixing classical music with jazz and African music. Now, my writing is going in that direction, but I can’t say where it will go tomorrow.

To hear Lionel Loueke's "Karibu", visit www.lionelloueke.com