Music for Heart and Mind

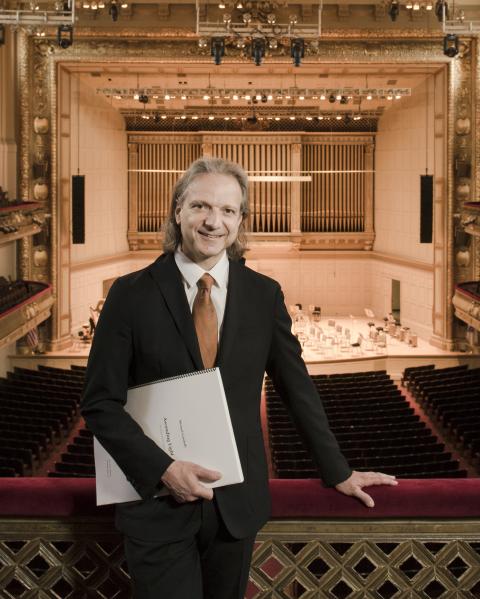

Michael Gandolf ’78

Liza Voll

For composers of contemporary concert music, receiving a prolonged standing ovation and repeated calls to the stage for bows after the world premiere of a new opus is quite rare. But in late March, Michael Gandolfi received both after the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) premiered his piece Ascending Light. The emotionally charged work (which he characterizes as an organ symphony rather than a concerto) received four performances by BSO conductor Andris Nelsons and French organ virtuoso Olivier Latry with the identical audience reaction each time.

Many factors contributed to the overwhelmingly positive reception. First, Gandolfi has a unique gift for writing music that is accessible and affecting yet thoroughly modern in its conception. Ascending Light was commissioned to honor the late BSO organist Berj Zamkochian, an Armenian-American, and to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the Armenian genocide that claimed more than 1 million lives. Consequently, Gandolfi crafted a 29-minute work representing the vitality of Armenian culture and a reflection on its tragic episode by integrating original thematic material with melodies from an Armenian lullaby and hymn tune. Imaginative writing for the organ and orchestration highlighting clanging tubular bells, insistent tympani, poignant double reed themes, ravishing string passages, and rhythmic brass jabs, evoked musical chiaroscuro.

Gandolfi’s music has attracted the attention of top conductors and commissioning patrons. His substantial catalog runs the gamut from works for solo instruments to chamber ensembles to orchestra to wind bands. In his search to find his musical voice, Gandolfi abandoned his original jazz and rock roots for a time to concentrate on the abstract sounds and techniques of 20th-century classical music. When he decided to bring all of his musical influences into the tent, he lost the interest of some who had championed his music, but quickly found new advocates. In addition to the BSO, other groups commissioning and premiering Gandolfi’s works include the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra; Memphis Symphony Orchestra; the Boston Modern Orchestra Project; the Los Angeles, St. Paul, and Orpheus chamber orchestras; the President’s Own United States Marine Band, San Francisco Choral Artists, the National Flute Association, and many more. His works are performed throughout America and Europe.

Growing up north of Boston, Gandolfi played guitar in a garage band unraveling the basics of rock and jazz while his two sisters played Bach and Mozart on the living room piano. Inspired by fusion artists such as John McLaughlin, Allan Holdsworth, Chick Corea and others, he entered Berklee during the mid-1970s, at 17. Pat Metheny, John LaPorta, and John Bavicchi were some of his teachers. After amassing three years of credits in an accelerated track, his burgeoning interest in composing led him to transfer to New England Conservatory of Music (NEC) where his classical works could be performed and he could study with composers Tom McKinley and Donald Martino. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in composition at NEC and now chairs the school’s composition department.

Gandolfi has an unusual talent for interpreting aspects of science, history, literature, and the visual arts and then colorfully conveying his take on them through Western classical instruments. Notwithstanding the heady concepts that frequently underpin his works, Gandolfi is no ivory-tower intellectual. He remains in touch with his original musical impulses. At a recent performance of a work for solo harp, he explained that his choice for stipulating the harp’s low strings be tuned to the key of E-flat was inspired by the low-tuning of guitars in heavy metal. His prelude, “Glasgow Shuffle” for wind quintet, has rhythmic ties to the blues. He accomplishes his musical goals with artistic integrity and stylistic breadth, never by artifice or gimmicks. The result is new music for the heart and the mind that resonates with a widening audience.

How did you develop the skills to become a composer?

My first proper lessons were with a Berklee grad named Eddie Marino [’76], a jazz guitarist and composer. I was playing in rock bands and reading chord changes, but not reading melodies at that point. Eddie got me working on Bill Leavitt’s guitar books, jazz repertoire, music theory, and counterpoint. He also introduced me to the music of Bartók and Stravinsky. These were very solid music lessons. I studied with him for several years and he encouraged me to go to Berklee to study composition and continue with jazz guitar.

In high school, I was interested in writing, especially as I learned more about the composers of the 20th century. There seemed to be a connection between the advanced harmonic language of jazz and that of 20th-century composers. In my playing, I was always drawn to things that were edgy and complex. For me, there was a progression from the Beatles and Rolling Stones to Miles Davis and John Coltrane to Bartók and Stravinsky. I always liked playing jazz and played through my college days. To this day, I love improvising.

Were there composers from the past that were especially influential for you?

It’s hard to say because things change over time. But since my childhood, J.S. Bach has been a favorite. His music never ceases to amaze me—the variety of music, the detail, and how compelling it is. Schoenberg, Stravinsky, Ives, and Bartók were enormous influences. I pull out scores and discover things in the music of Debussy, Ravel, Rimsky-Korsakov, Shostakovich, Sibelius, and Strauss. I have studied the symphonies of Sibelius, Shostakovich, Bruckner, and Haydn over and over.

When I was younger, I’d make a 90-minute cassette of music and listen to it continuously. I’d fall asleep listening so the music got into my head. I did that with Allan Holdsworth’s [guitar] solos, I could sing them. I also loaded recordings of Bruckner’s symphonies onto my listening device and looped them. Wherever I went I had the headphones on. I got to where I could sing through all of them.

Can you talk about your composition studies with the late Tom McKinley?

He was a great teacher. He wanted students to just do the work and write a lot. He had great facility at the piano and could play anything you came in with. After he played your piece, he would give his gut feeling about it. He suggested a lot of repertoire to listen to and books to read—from philosophy to music history. It was a broad education and he talked a lot about little details of the pieces I brought in. It was interesting that after I’d finish a piece and have it performed, he would rip it apart in terms of its long-range aspects. I wondered why he hadn’t mentioned these things as I was working on it, then realized that this was how he worked. He didn’t revise he just went on to the next piece. He advocated writing yourself into shape and not worrying about whether your grand statement was working. He took particular interest in my work and showed me a lot about composition. In my other classes I studied species counterpoint, harmony, and orchestration.

What prompted you to re-examine your approach and let your jazz and rock roots have a place in your concert pieces?

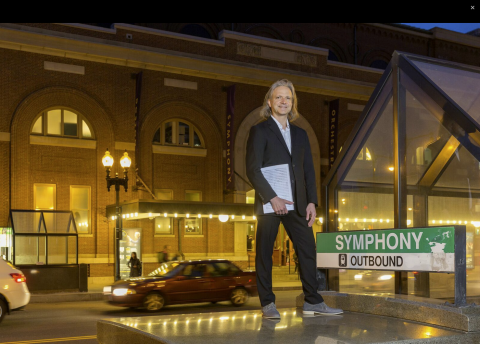

Michael Gandolfi '78

Michael J. Lutch

I had to suppress some things to learn others. I wouldn’t trade the pitch manipulation ideas I learned from being a 12-tone composer for anything. It was kind of severe at the time, but looking back, I see that it has informed me about all kinds of music that deals with 12 notes, whether it is diatonic, pentatonic, or something else, it’s all part of the same big family. Now I can move between the worlds easily. So if I had not shut out some things to learn about that I wouldn’t be able to do what I do now. I’m not regretful about it. I was able to move beyond the myopic view that a singular kind of thinking brings on.

When you started, did you look at the economic realities of a career as a composer?

I think I was crazy enough when I was younger to not worry about things like how I would pay my rent. I’ve been fortunate. I tell my students about how naive I was, and maybe that is important. Being too careful could be detrimental. You can’t play it safe. You have to go for it but you don’t want to become destitute. I tell my students that they are good musicians, they play an instrument, and can do things that others in society can’t do. Maybe you take this for granted because you hang around with musicians. But, you have unique talents: use them. I used to play with a classmate who was a flutist for bar mitzvahs, weddings, and G.B. gigs all over the place. I taught guitar lessons at my house and traveled to students’ houses for a while before I got a job teaching at Phillips Academy. I also copied music by hand. I did anything I could that was music related for a long time to support myself as a composer.

So I think you have to be a little naive, but you also need to be resourceful. You can’t write 24 hours a day, so practice and do the other things musicians do. We can all survive and be successful in our time. Some will get commissioned quickly, for others it will take 15 or 20 years. Though it sounds like a cliché, perseverance and belief in yourself are also part of the game. When the bell rings, you need to be ready. What’s most important is that you write pieces. It’s not about knocking on doors and passing out your résumé. Spending too much time doing that means you write fewer pieces each year. Be ready so that if someone asks for a string quartet, you have a couple ready to go. A composer needs to be prepared.

How does one embark on a career a composer?

There are as many ways to do this as there are people doing it. For me, summer camps were important. I was fortunate to get into the Composers Conference, the Yale [University] Summer School of Music and Art, and the Tanglewood camp. The summer camps put you in with the cream of the crop. There is an accelerated learning process and you meet people there who become lifelong friends, mentors, and colleagues. Those summer programs, plus my education at Berklee and NEC, were very important for my development as a composer.

There is no real fame or fortune in this field. If you are seeking that, you’re looking in the wrong place. But there is a small and devoted group of people who will step up to the plate for composers and commission works, get them performed, and champion them. I think they will always be there.

You are often referred to as a “tonal composer.” Do you agree with that description?

People have been classifying me as a tonal composer, but I don’t see myself that way. I don’t sit down thinking I will write something in B minor, I still think like a 12-tone composer. I think about the large movement of pitch, the fundamental notes that might move around, and local harmony—the field of notes and their progression. I do like triads and I work with big triadic structures.

I started writing late in the 20th century when there was so much emphasis placed on originality—finding your own voice and not connecting to anything else. But really, the emphasis was on being original—as long as your music sounded like Schoenberg! There is something funny about that.

In my field there’s a battle between those who write abstract music and those who write “tonal” or comprehensible music. I welcome the variety of it all. It would be a very boring place if we all wrote in one style. I’m thrilled that there is probably more diversity than there has probably ever been in the history of music making. We all choose what we want to do.

Do you start a piece by mapping out and imagining how you will portray the concept you have in mind?

In the creative process I cast a wide net, but my response to whatever I am bringing in is always a musical one. What I do best is to speak notes. Somehow if I read about the latest trend in physics I can get inspired and start imagining notes. It’s almost like synesthesia. I don’t have that, but some people can smell something and see a color. I think I have an artificial version of it where a stimulus comes up and I conjure up a musical response. It’s not always direct, but as I think about a topic, I can get myself into a frame of mind where I come up with notes that relate to it.

Some of your works are inspired by mathematic or scientific concepts, historical events, or emotions drawn from the visual or literary arts. How do you come up with musical ideas for those things?

I don’t often come up with the concept for a piece myself. The commissioning agent will suggest something as happened with Ascending Light. But the idea for The Garden of Cosmic Speculation came through reading a book about that [sculpture garden created by Charles Jencks in Dumfries, Scotland]. I thought it would be fun to explore that in a piece of music. ForQ.E.D. Engaging Richard Feynman, I read Surely You’re Joking Mr. Feynman and other of [the physicist’s] books when I was in junior high school. I found him to be an engaging character. When I needed to write a piece for chorus and orchestra, I wanted to use texts that related to his writings.

But I never think of these pieces as being purely programmatic. When I write, the bottom line is the music, not the story behind it. This is true for Ascending Light too. Yes, there is an extra musical element in it, but you don’t need to know anything about that to experience it as a cogent piece of music. It’s a nuts-and-bolts piece about pitches and harmony.

You’ve said that improvisation is part of your compositional process. Do you improvise themes or a groove and then develop them?

All of the above. With Ascending Light, when I needed a new idea, I’d turn to the keyboard and find something to work with. When I was writing music for a production of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, I took my guitar and came up with a little thing that fit nicely under the hands. Then I moved it over to the piano, violin, and the ensemble. Sometimes I improvise to find chords, but it might be something [improvised] from singing or tapping a rhythm too. I believe that we as musicians have stored a lot from all the music we’ve listened to—from studying, going to concerts, listening to the radio. It’s all there in us; we just have to tap into it. When I write, I believe I am digging into those resources and finding something, I’m not creating anything original. I can’t tell you where it comes from, but if it wasn’t for all the listening I’ve done, there’d be nothing there.

Is creating an emotional response in contemporary concert music secondary to other esthetic concerns?

I learned a long time ago that I can’t predict what someone’s response will be and I’m not trying to manipulate their response. I always write for myself because I think that’s what we’re supposed to do as artists. I am the one who has been walking around for months with Bruckner and Haydn symphonies in my head, so I should be self-indulgent in a sense, draw on all that experience and bring it out. I don’t have any control over what happens after that.

The premiere performances of Ascending Light got a tremendous response from the audiences in Boston.

As I wrote the chorale section of the piece, I got goose bumps and had to step away from the table a few times because I was losing it. That part is so emotional. After the piece was played, there were some people sobbing in the hall. I felt emotional hearing it in rehearsal. While it might not always be true, if I as the composer have a strong emotional reaction, I guess we can assume that a certain number of people will also react to it.

But I didn’t do anything so that people would take out their handkerchiefs. I didn’t try to make that happen. It’s just what came out, and it was powerful. Everyone comes to a listening experience with a different history. You’re setting yourself up for failure if you try to manipulate people in a certain way. Maybe if you’re writing music to go with a visual image in a film, you can be more assured of what will happen. But when it’s just an abstract piece of music, we all bring too many different associations to the table. A listener doesn’t have to feel moved during the chorale for the piece to be successful. If a piece is put together with integrity from what you had in your heart as you wrote it, all the other stuff will take care of itself. If you make an honest effort and delve into what you feel is tasteful, that’s all you can ask of yourself.

You’ve said that composers are storytellers. Can you elaborate on that?

Everything we do in life is storytelling in a way. Even when we’re teaching, we are telling a story. We need face-to-face storytelling as humans. Music is just an upper-echelon expression, storytelling.

When we compose a piece, we are creating a story. And I don’t mean an extra-musical story, the notes themselves are communicating to us. It’s another reason why I have respect for the craft of composing. You have 2,000 people in the hall listening to your tune, to the story you are telling. It is tremendously gratifying and humbling at the same time. It is extraordinary to hold the attention of that many people for a period of time as well as the musicians who are bringing it all out. It’s an enormous responsibility.

That relates to the hard-work aspect. If you are going to hold the audience and musicians in some kind of rapt attention for a time, you have to take it seriously. I really think music is a form of storytelling that is fundamentally no different from moving about in our daily lives telling stories to one another. They may be news stories, personal experiences, teachings, or preaching. All around us wherever we go, it’s just one huge story with all of these different manifestations of expression. So music may be the most abstract of the ways of telling stories. All brands of music don’t appeal to everyone, but music provides nurture to those who respond to music and feel a need for it. I couldn’t go a day without listening to something. Not everyone is like that, but those in the music community are like that. It’s a form of sustenance.

Composition brings you to this type of revelation. You get philosophical about all kinds of things. A psychologist once told me that storytelling is a big topic in psychology. I didn’t know that. But when you are in a creative state, you tap into other things happening around you that you weren’t privy to in a literal sense. Then you find that you weren’t alone in thinking these thoughts. It’s been happening to me a lot lately where I discover something through my work and then I hear that someone in another field has had the same thought. Even the most complex scientific concepts are a form of storytelling. If we all have storytelling at our core, there will be connections made across all boundaries.

Many composers today get commissions for a one-movement, eight-minute piece. You typically get commissions for more lengthy works.

I’ve gotten both. In the summer of 2013, I was commissioned to write a five-minute concert opener for the BSO. But mostly I get to write substantial pieces like Garden, which fills a whole program. Twenty minutes to a half-hour is about the average for my commissions these days. When I was younger, a 20-minute piece would have seemed daunting, but now it doesn’t feel that long. Forty minutes would feel long. Ascending Light was about 1,200 measures. I used to feel proud if I wrote 200 bars, but now I write that in a week.

Does a composer have to hustle to receive performances of his or her works?

I have sent my music around unsolicited only once and it was a bad experience. I should never have done it. I sent music to a conductor whom I knew, but I should have realized that if he was interested in my music he would have contacted me. It shouldn’t have been at my prompting. Doing that made the relationship awkward for a while. There are some colleagues who are more aggressive than I am. They do it naturally and it’s part of their personality, and they succeed with it. I marvel when I see this, but I could never do it. We have to realize who we are, and I am just not that way. I have been really lucky to have great people come to me. They become advocates and get other people interested. I am content at this point in my life not to make any changes. I take what comes my way and do the best with it.

I think there can be a tendency to always want more no matter how much is being given to us, and that’s not a nice place to be. You should take what you get, be happy with it, and go on to the next thing. I see myself as a functioning member of a segment of society; I provide music. I’m a composer—period. There is a utilitarian element to it. Others come in and fix up your house. But this is what I do best. I show up for the job and get completely invested in it.

It’s all about hard work. When I first approached my dad about providing tuition so that I could go to Berklee, he said he’d support me only if I worked as hard as I possibly could. He didn’t ask me to be successful or tell me that I had to earn a good living. At the time I didn’t realize how significant it was that he didn’t put any extra pressure on me. So if I had failed but tried hard, he wouldn’t have questioned what I was doing. That’s how he was in his life and I inherited that work ethic from him. I’d tell young composers to work as hard as they can, and they will be fulfilled and satisfied. You won’t walk away feeling like you should have given it a little extra.