Anatomy of a Classic Song

It’s a rare phenomenon when any song—even a huge hit—has such emotional power that it affects people worldwide for generations. Paul Simon’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water” accomplished that feat, sending ripples around the globe that are still present today. Within a month of its release in January 1970, it sailed to the top of the Billboard charts and stayed there for six weeks. The album of the same name topped the charts for 10 weeks in the United States, and 33 weeks in the United Kingdom. To date the album has sold 25 million copies around the world, with 5 million purchases in America alone. In February 1971, it also won four Grammy Awards.

In the intervening four-plus decades, more than 200 artists of various styles and ages have recorded or given high-profile performances of “Bridge.” Singers covering it early on included Aretha Franklin, the Jackson 5, Elvis Presley, Willie Nelson, Elton John, Whitney Houston, and dozens more. More recent renditions by younger artists include those by David Archuleta, Josh Groban, Clay Aiken, BeBe and CeCe Winans, Leona Lewis, and Charlotte Church, to name a few. Artists from the United States to Sweden to China have performed it. The December 9, 2004, issue of Rolling Stone which profiled the 500 greatest songs of all time, ranked “Bridge” at number 48.

When “Bridge” hit the airwaves, American society was in turmoil over the Vietnam War in Southeast Asia, which was spilling out in protests onto America’s streets. The quiet assurance of Simon’s lyrics delivered in Garfunkel’s sometimes gentle, sometimes soaring, tenor to the accompaniment of Larry Knechtel’s gospel-infused piano also subtly connected to the period’s racial struggles and to the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968. The turbulent decade of the sixties that had witnessed the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy had just come to a close. For millions, “Bridge” served as a musical emollient for life’s public and personal struggles.

More Than Music

Simon has told interviewers that he knew immediately that he had written something special, something exceeding even his high standards. He has cited the rendition of the spiritual “Oh, Mary Don’t You Weep” sung by Reverend Claude Jeter and the Swan Silvertones as providing musical and lyrical inspiration. The line in the spiritual, “I’ll be a bridge over deep water if you trust in my name,” reveals the connection.

In the video the The Harmony Game, Simon speaks briefly about the simplicity of his lyrics mentioning these:

When you’re weary, feeling small/ . . .

When evening falls so hard, I will

comfort you.

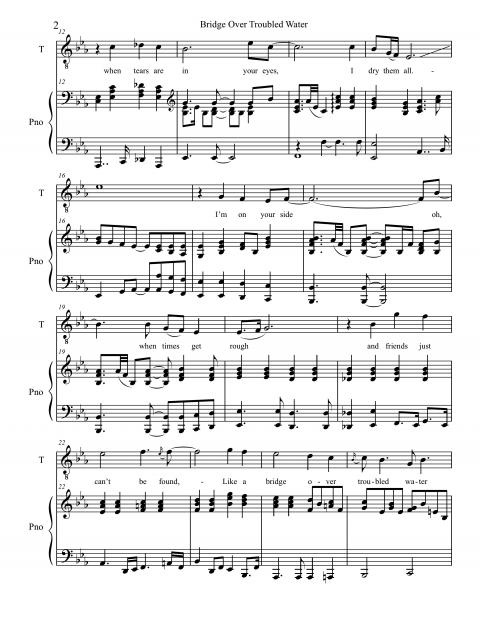

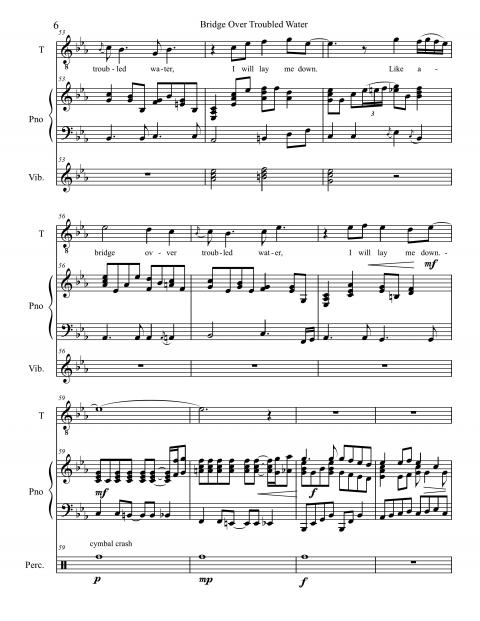

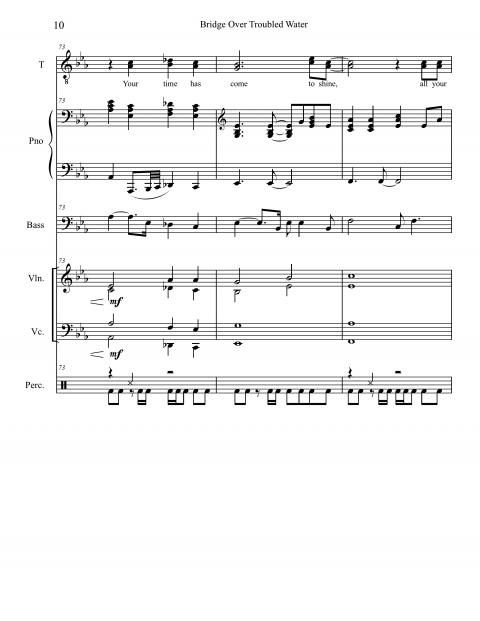

The melody is one of Simon’s best, extremely sing-able and catchy. The first half of the verse hovers around a G above middle C. In an interview, Garfunkel stated that in an early take, he was not singing the octave glissandi in bars 15 and 43. Simon rightly asked him to put them back in, restoring one of the song’s first melodic hooks. The melody is long for a pop tune, with the last line of each verse, “Like a bridge over troubled water, I will lay me down,” always sung twice. The intensity increases each time the melodic action goes up an octave.

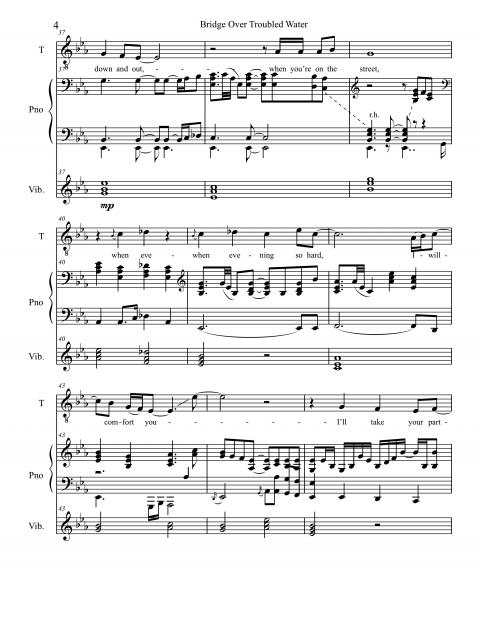

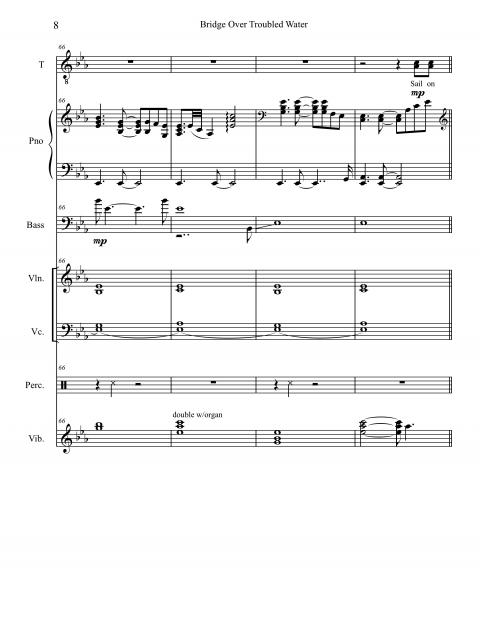

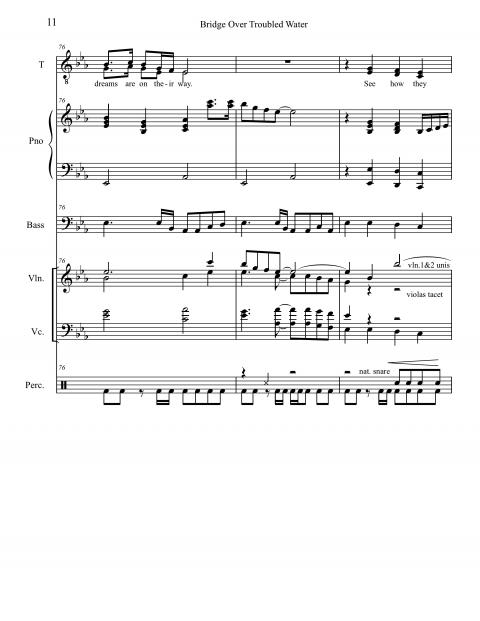

The third verse introduces the trademark two-part harmony that Simon and Garfunkel (S&G) were known for. Simon has said that he always felt that the lyrics to this verse didn’t fit with those of the first two. Its first line, “Sail on silver girl,” probably sounds more oblique or exotic to listeners than what Simon told one interviewer he was writing about. He said once that it referred to his first wife (Peggy Harper) discovering her first gray hairs.

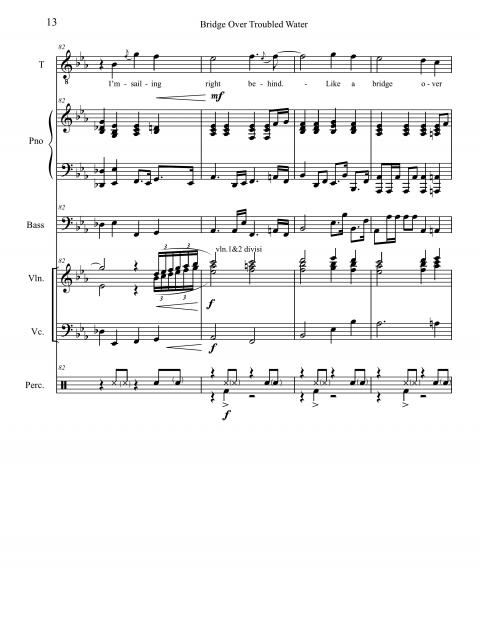

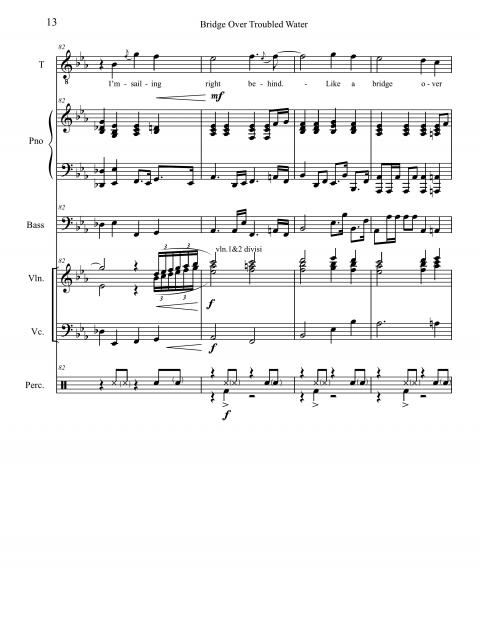

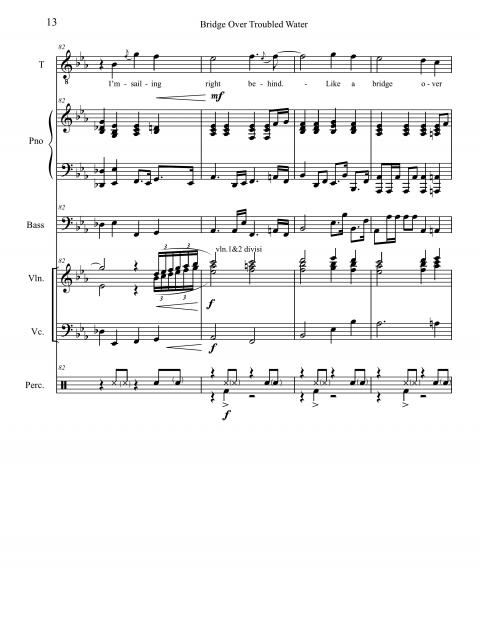

In bar 80, as the production builds toward the climax, Garfunkel sings forcefully. He hits the song’s tessitura (an Ab above the staff) in bars 89 to 91, and both the instrumental and vocal parts arrive at the song’s emotional peak.

The Sessions

In addition to Knechtel, S&G brought in studio drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Joe Osborn to record the instrumental track at Columbia’s Gower Street studio in Los Angeles. At the time, those three musicians were known as the “Hollywood Golden Trio” for the many hits they’d played on, and were a subset of the larger collective of studio aces called “The Wrecking Crew.” Osborn played two electric bass parts. Blaine did not play a full drum kit, only select drums and cymbals.

While recording in Los Angeles, S&G sang together at the top of verse three and got a good take. During those sessions, it was agreed that Garfunkel had nailed the vocal performance for the rest of the third verse—the most dynamic and emotional section of the song. He would record the first two verses later in New York. In many interviews, Garfunkel has said that having finished the climactic verse first enabled him to better shape the arc of the song by understating the first and second verses.

In Michael Hill’s liner notes to the 2011 commemorative Bridge album reissue, Garfunkel recalls that it was easy to sing the second verse, ramping up the intensity leading to the final verse on which he’d already pulled out all the stops. But the first verse had to be a contrast, really delicate, and that challenged Garfunkel. “After about eight sessions of trying to get the first verse right in its extreme delicacy, I had to take a break,” he says. Garfunkel left the studio on Manhattan’s 52nd Street and walked to St. Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue and sat in one of the pews for an hour. “I invoked the larger powers, then went back to the studio and got it.”

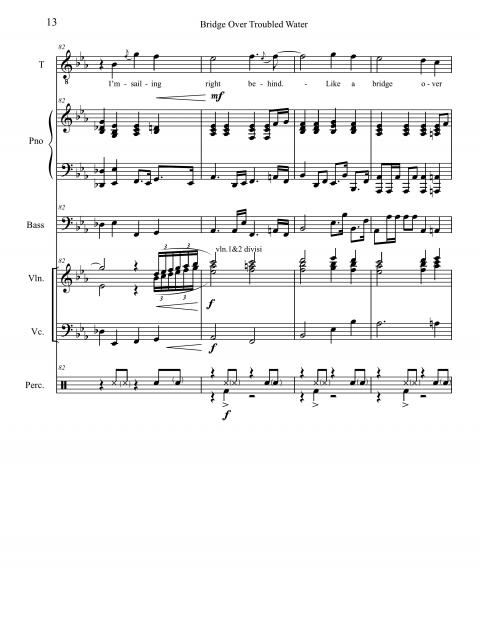

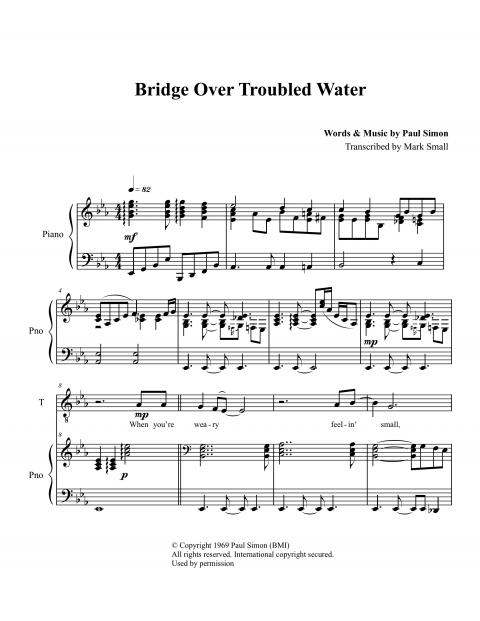

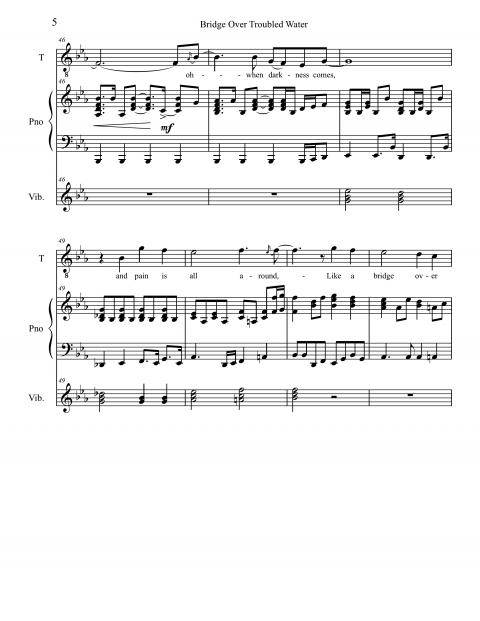

The Score

Knechtel plays a masterful intro—majestic from the first chord—that quickly sets the gospel tone. It’s replete with gospel chord movements. In the second half of bar 2 through bar 4, he plays a bass line rising from the root of the IV chord (A♭), up to a C7 chord by employing a series of unresolved secondary dominant chords. The A diminished chord on beat four of bar 2 moves deceptively to the I chord in second inversion. That I chord becomes a dominant seventh that also moves deceptively away from what the ear anticipates, to what sounds like it will be a V7/ii. But instead of going to the ii chord (F minor), that C7 resolves deceptively to the IV chord.

During the last two beats of bar 4, the A♭ chord changing to A♭ minor, further mines the gospel style. For the last four bars of the intro, Knechtel plays a tonic pedal note on an E♭ and the chords above change from E♭ to E♭ 7 to A♭. The final plagal cadence (from IV to I in bars 8 to 9) provides more of a church feel, and sets the stage for Garfunkel’s vocal entry.

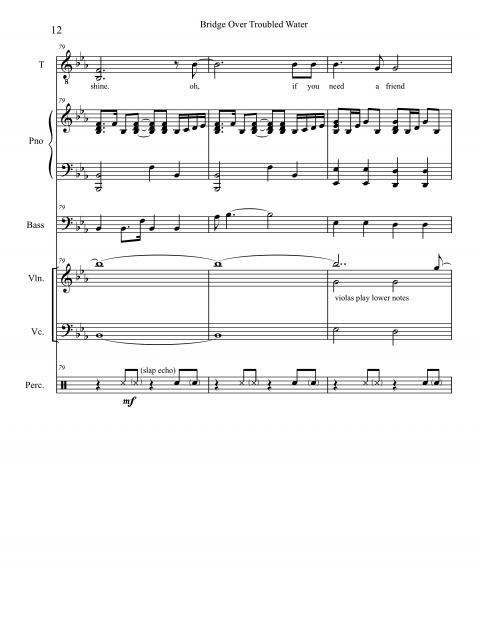

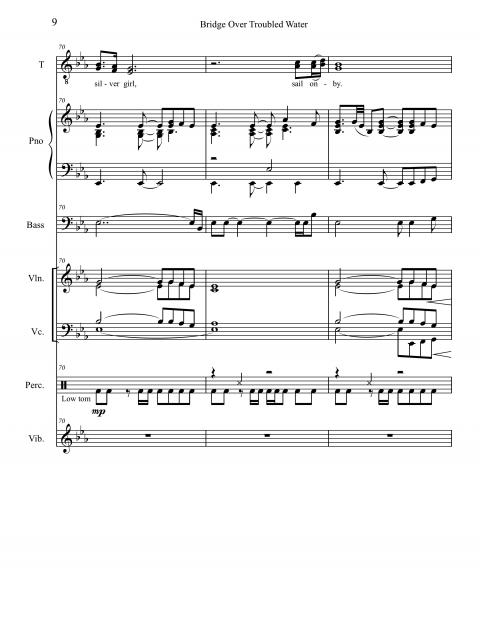

To add spring to the rhythm, Knechtel inserts occasional syncopations in the left hand, playing double-dotted quarter and sixteenth notes (bars 12, 15, 27, 28, 39, 68, and so on), and in other places dotted-eighth- and sixteenth-note rhythms (bars 21 to 23, 40, 48 to 49, and 88). After dominating for nearly the entire song, the piano part thins out considerably, passing the baton to the strings and percussion to carry the coda (bars 94 to 99).

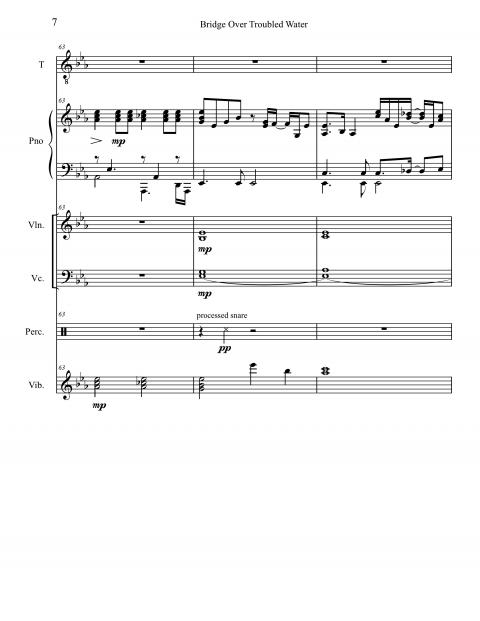

The production begins its slow and subtle build at the top of the second verse. Simple chordal pads played on vibraphone broaden the instrumental texture and add a shimmer to the mix. It should be noted that transcribing music from a song’s full mix (without access to the stems) is not an exact science. What’s notated on the score is what is perceptible in the mix. It’s possible that more notes on some instruments are present but masked by other instruments or by the reverb. The vibes part is a case in point. The vibes enter quite noticeably and then recede in the mix. In bars 37 to 42, I hear triads, but the part is heard intermittently beginning in bar 41, and alternates between triads and two-part chords from bar 43 forward. It sounds like an organ is quietly doubling the vibes in bars 67 to 69. (The very last notes of the song as the strings fade are those of an E♭ triad played pianissimo on the vibes.)

The bass makes its appearance in bar 66. Two basses are clearly heard on the right and left sides of the mix. The first enters with high notes in bar 66, and a lower bass slides up to an E♭ in bar 68. The overdubbed, high bass part may appear again later, but if it’s there, it’s not audible enough to be notated.

Hal Blaine didn’t lay down a typical drum groove but played the components of the kit in a quasi-orchestral style. Both contemporary and more recent interviews with Simon and Halee indicate that they did a lot of experimenting to achieve the desired effects on the drums for the Bridge album. Each drum sounds as though it’s on a separate track; the reverb and delay settings vary for each. The snare drum has three different sounds. For the heavily processed snare tracks, I’ve used an X for the note heads (beginning in bar 64). I’ve used the same for the processed snare that has a slap echo (see beat 2, beginning in bar 79). The echoed note is in parentheses. On beat 4 of bar 79 a more natural-sounding snare is written with a standard note head, and its echo is in parentheses. While the drums play only in the last third of the song, they add tremendously to the drama—especially the cannonlike hit on a low tom or bass drum in bar 94.

“Like a Pitcher of Water”

Freeman, a seasoned pop arranger, understood where the strings should lay back and where they should come forward. The strings enter with chordal pads (bar 64), and break the texture to double and amplify short piano melodies in bars 70, 72, and 77. A long, sustained note on Bb above the staff begins to build the drama in the violins (bars 78 to 81). In imitation of the vocal melody, the violins drop from the B♭ to a G on beat four, bar 81. A sixteenth-note triplet run at the end of bar 82 leads to a sequence of high triads that build further intensity.

Seizing a spot for the strings to break out, Freeman wrote a series of quarter-note triplets in octaves for the violins that foreshadows Garfunkel singing that rhythm in bar 90. I made an educated guess that the violas play the lower notes of the high triads appearing in bars 83 through 99. At first glance, the spacing between the cellos and the violas seems very wide. Given his experience writing string charts, Freeman would have known that anything written in that middle range would likely get lost in the mix. Pop songs typically have lots of other sonic information in that register.

Coda

In his autobiography The Soundtrack of My Life, legendary record executive Clive Davis recalls that, after first hearing “Bridge,” he insisted that it be issued as a single. This surprised S&G because it bucked the trend in radio in 1970, which was moving away from ballads and toward the heavier sounds of Hendrix and Led Zeppelin. “When you’ve truly got a great song, a potential all-timer, that trumps all the rules,” Davis wrote. History proves he was right.

Examining the score, it’s hard to account for the amount of texture, color, and powerful emotion coming from just voice, piano, bass, percussion instruments, and a string section. The musical skeleton of the song is laid bare in this score, but still, it only shows the components of the structure. A score can’t indicate the innumerable musical subtleties, inflections, and other intangibles that make this recording so compelling. It’s the sum of all of the parts that assured “Bridge” a place among the iconic entries of the Great American Songbook.