The Woodshed: Exploring New Harmonic Frontiers with the Thirds Chart

Scott Free ’75 is a professor of jazz composition and a member of ASCAP. You can hear excerpts of his music at www.myspace.com/freemusepublishing

Phil Farnsworth

Many great contemporary jazz tunes have harmonic progressions that elude explanation through functional relationships. Without a guide, it can be difficult to break out of functional harmonic chord progressions. This lesson’s goal is to help composers who have explored the fundamentals of music and need fresh harmonic ideas. (And for a sample of titles featuring non-functional progressions, see “Functionally Elusive Tunes” sidebar below.)

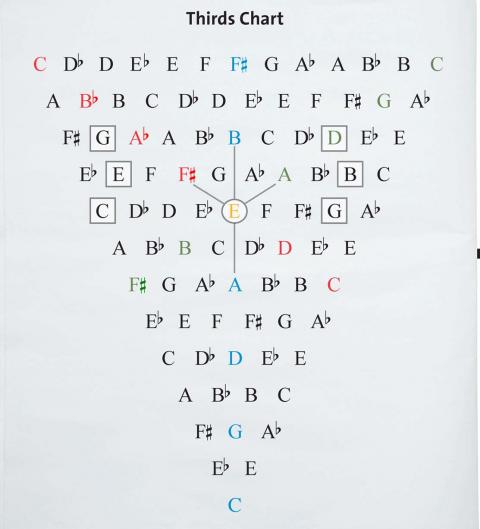

Years ago, Berklee Professor Mick Goodrick showed me a chart he got from a composition student (see “Thirds Chart” on page 29). The letters represent notes arranged in thirds when read vertically and chromatically when read horizontally.

At the time, I didn’t give the chart much thought beyond its geometric configuration as a triangle. But after I began teaching composition, I turned to this tool to find unusual chord progressions in contemporary jazz.

Triangular Vision

If you look at the chart from the bottom with the note C, the outer row of letters on the right moves up in major thirds to create a series of augmented triads. The row on the left moves up in minor thirds creating diminished seventh chords. The top row (from left to right) forms a complete ascending chromatic scale. The seven notes in blue letters (starting from the bottom and moving up through the middle of the chart) leap in fifths, but when reordered, they form a C Lydian scale. Moving from the upper-right-hand corner downward diagonally to the left (see green letters), the movement is in descending fourths, and the notes form the same Lydian scale. The red letters that move downward diagonally to the right form a descending whole-tone scale. All three colored rows intersect with the gold, circled E near the middle of the chart.

Observing that the blue and green rows move in perfect fifth intervals and knowing that fifths invert to fourths, I started working with the elements from the chart. I constructed three-note voicings in fourths derived from notes of either the blue or green lines, moving in fifths or cycle 5. I placed the voicings over the descending chromatic line taken from the top line (from right to left). Example 1a shows the result. Example 1b uses the same material with the chordal structures inverted and voice led for smoothness. Example 2 shows the fourths voicings placed over an ascending chromatic line (taken from the top line read left to right). Once again the same chords are voice led in example 2b.

Useful Patterns

The resulting chords reveal a useful pattern of chord types that repeats as you move through the complete chromatic scale in the bass. Example 1 has a major-seventh chord with a #11 followed by a sus 4 chord. Example 2 features a three-chord pattern: major 7 #11, a major triad with an added 9th with the third in the bass, followed by a sus 2 chord. The fact that a chromatic bass line moving in either direction works testifies to the flexibility and seemingly endless possibilities of combining voicings in fourths with different bass notes.

In one of my pieces, I use the three-note voicings in fourths with their inversions moving in cycle 5 against a descending chromatic bass line (see example 3). Using the entire chromatic scale lengthened the arc of a progression to create momentum. In working with this idea, it served my purposes to make chromatic shifts in the voice leading when it became necessary to make key-related choices.

With the augmented triads derived from the outermost line on the right-hand side of the chart, I made a progression of augmented triads descending chromatically over a bass line moving in contrary motion in ascending minor thirds. These notes are derived from the row of letters moving up the left side of the chart. The result is a series of minor chords with major sevenths (see example 4). Choosing a bass motion descending in fourths is another option. Making the bass move in contrary motion to the voicings strengthens the effect of these combinations.

New Relationships

The chart can help with melodic as well as harmonic material, The first five notes of the green line (moving from right to left) can be rearranged into a pentatonic scale. Example 5 shows a pentatonic melodic motif descending in whole steps against major seventh chords that ascend in minor thirds. Example 6 is a series of major triads moving down in major thirds over a descending chromatic bass line.

These are just a few of the possible ways to use elements of the chart to find fresh ideas. The more you work with it, the more musical relationships and tools you will discover. For instance, the notes in rectangles show how moving to the right and upward, and then upward and over to the left yield major triads. These musical examples show how taking a small concept and turning it in different directions according to your intuition can help bridge the gap between where you are now with your writing and where you would like to arrive next. I hope this lesson helps you to build a bridge or two.

Functionally Elusive Tunes

“Lost” by Wayne Shorter

“Tell Me a Bedtime Story” by Herbie Hancock

“Heyoke Suite” by Kenny Wheeler

“Sno’ Peas” by Phil Markowitz

“Skittish” by Jim McNeeley

“Stray” by Richie Beirach.

“Van Gogh’s Left Ear” by Kenny Garrett

Thirds Chart

Examples 1a-2b

Examples 3-6