Confessions of a Serial Rusher

Bill Gordon

Life at the front of the beat and beyond can be a problem. I was first found out at a gig as a teenage drummer in Baltimore, when the large and much older bass player strolled over midsong and said gently, firmly, "What's your hurry, son?" Decades later, in New York City, I was trying to put a piano track down for musical cohort Chris Cunningham. No matter how much I held back, I could not put it in his pocket. I never did get a good take. Rushing can cause other players such discomfort that they won't want to work with you. I cringe recalling gigs that evaporated because I'm Mr. Speedball.

My pupils are well drilled on developing solid time, yet rushing seems a natural tendency for many kids and aspiring pros alike. For some, pushing the beat feels not only natural but correct. In jazz, it happens more during soloing than comping. Some rushers work fine with a metronome; but take that click away, and zoom! This article presents the different and sometimes contrasting philosophies of a few seasoned educators and players and recommendations for developing a better time feel.

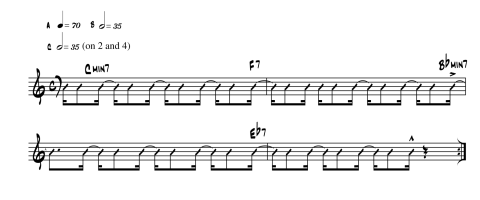

For some, rushing seems to stem from anxiety or tension. Distraction because of current or old performance injuries can also tighten us up so that we push the time. The traditional antidotes: breathing, relaxing, and listening more deeply help considerably. They allow the body and mind to be aware of how to interpret time. It can be important to sit fairly still, not tap the feet too vigorously, and listen for the end of each note. Musical examples 1 and 2 can help you learn to avoid drawing the beat earlier and earlier as you comp. If you have Pro Tools or a similar setup, record a few minutes of a metronome click. Next, mute all but the first two bars. Use those bars for a count-off and then record yourself. Breathe, relax and practice.

Berklee Professor and jazz pianist Jeff Covell calls a musician's concept of time a "craft issue" that most of us have to work on. "There are degrees of time, starting with a general sense of where the beat is to a deeper sense and sensation of where you are within the beat," Covell says. "Even the simplest rhythmic task can be very challenging to execute well when using all four limbs. Working on this coordination issue can help to develop a sense of balance and stability. Many good players have an interest in and a history of playing the drums, which focuses the body's sense of rhythm." Covell also suggests setting your metronome to click on beats two and four to develop your swing feel. "In ensemble playing, time is flexible," he says. "Just listen to the Miles Davis album Four & More. While most would agree that it is bad to rush, it's far worse to drag."

The answer to developing a good time feel comes through understanding subdivision of beats and rhythmic shapes according to bassist and Berklee Professor Danny Morris. "You can think straight eighths, swing eighths, and triplets, but there is more to it than pure metronomic quantization," Morris says. "We are all individuals; certain grooves that can be easily played by some are profoundly difficult for others. We should celebrate the fact that we all have individual voices on our instruments.

Ex. 1

EX. 2

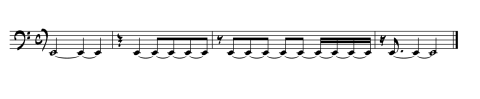

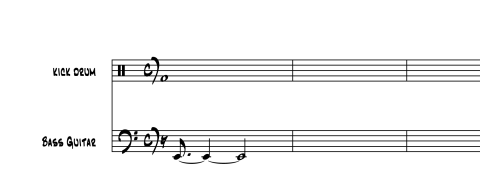

Ex. 3

Ex. 4

Ex. 5

"Musical example 3 can help improve and broaden time concept," Morris continues. "In order to play this effectively, think of the shape of the upcoming rhythmic figure. This visualization of the subdivision appears in example 4. As the rhythmic figure approaches, the player should already be mentally subdividing the pulse. This helps to feel the sixteenth-note syncopation when it occurs in bar four.

"Within this framework lie shapes that are susceptible to molding or movement. Charles Mingus had a rhythmic concept that he called rotary perception. He described drawing a circle around the beat. Anyone in the ensemble was free to play within this circle. At any point, a new circle could be drawn redefining the center point of the beat. This creates a migration of the downbeat to a different part of the bar, producing a distinctive groove and feeling. The laid-back phrasing in the style of Count Basie's tune 'Lil' Darlin' or the style of a Ray Charles vocal has recently been passed down to Ahmir 'Questlove' Thompson (drummer with The Roots) and Pino Palladino [bassist with D'Angelo]. These artists currently use the rhythmic figure from bar one of example 3 and superimpose on it the time concept found in bar 4 of example 4 [see example 5]. The end result is a flam between the bass and the bass drum. While some might hear this as a mistake, this alignment is the desired result. This effect can be heard on D'Angelo's Voodoo CD or any number of neo-soul or hip-hop CDs.

According to Morris, "When studying music styles, it's interesting to note the evolution of time. Yin and yang, the mystical alchemy found in all things including natural time, seems to be producing some bold and lovely shapes in the modern rhythm section. These shapes celebrate the spirit of the times by fusing jazz, soul, hip-hop, rock, Latin, and other styles."

Paul Schmeling, who chaired Berklee's piano department for 30 years, advises on the basics. "Avoid feeling frantic mentally or physically," he says. "When you're soloing, leave some space, play fewer notes. If muscular tension causes you to push the time, work on the area of your technique that creates the tension until it no longer happens. Tapping your feet gently - especially alternately - is okay; but just toe movement is even better. Violent foot tapping or leg pumping builds tension that almost always gets into your playing-often as rushing."

To help fine-tune your time, Schmeling suggests learning to feel only beats one and three, and, at faster speeds, just beat one. A metronome that goes really slow (down to 10 bpm for whole-note work) will help. Playing scales and arpeggios with the metronome clicking on beats one and three or better yet, just one reinforces the longer pulse. "Really land on one and three," says Schmeling. He is not a fan of setting the metronome to click on two and four, despite how good it feels when you're working on swing feel. It's an understandable notion, growing up with jazz and rock 'n' roll's accented backbeat, to think of that as the deal. The James Brown band, the tightest and groovingest r&b band of the 1960s, was drilled relentlessly in rehearsal not to the backbeat, but to what they called "the big one."

Jazz vibraphonist and longtime Berklee educator Gary Burton suggests practicing with a metronome in order to develop a steady sense of pulse. "I don't think it matters when the clicks happen," Burton says, "although in a straight-eighth-note feel, clicks on every beat or on beats one and three would be best.

"I also recommend listening back to your own solos via recording. I had a tape machine when I was a kid learning to improvise. I noticed all kinds of deviations. Some were small and unnoticeable to me while I was in the heat of playing, but some were big-time goofs. It was very helpful to my subconscious mind, which is where our sense of time and pulse is located, to hear the results back on tape. Can you imagine judging your physical appearance without a mirror? You'll learn about things other than time from this kind of reflection and analysis, but time and consistency in rhythmic execution is probably the most major skill to be mastered through practice and observation."

The tendency to rush seems to diminish with age. My version of time travel is not as apparent these days, although I still ask the bass player at sessions or gigs to keep an ear on my time, for I know the beat creep lurketh still.

Schmeling's most sage observation may be that a little rushing is okay. "If the music is cookin', let it be." He reminds us that on cuts from Miles' Four & More album (featuring Tony Williams, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, and George Coleman), a seminal jazz record studied by many serious players, even these great musicians are rushing like bandits! Schmeling also makes it clear that whatever works to improve our time or anything else is what each of us must go with. Schmeling also advises going easy on yourself and your shortcomings. Enjoy what you've got, put it to good use. Master cellist Pablo Casals told an interviewer why, at age 90, he still practiced every day, "Because I think I'm getting better."