Looking In, Looking Out

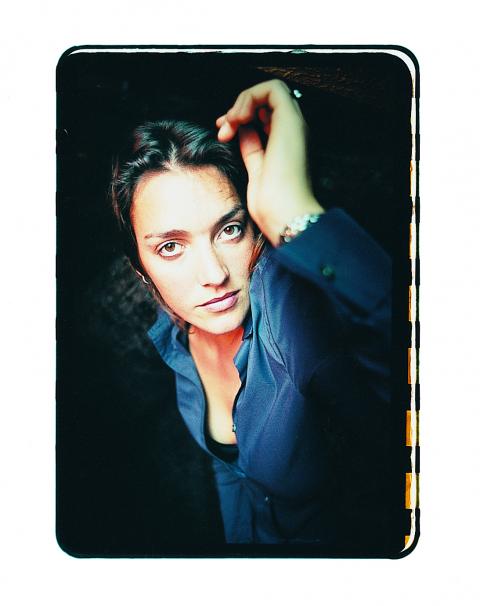

Singer/songwriter Jen Chapin

During my first semester at Berklee, I would lock myself in a practice room and spread my New York Times out over the piano keys. There I would sit, slumped over with guilt as I dug into the news. It would take a while before I would get around to my Ear Training, and my reading would be taunted by fluid scales of other fingers that filtered in from adjacent practice rooms. A friend walking down those long aisles of discipline might spot me through the little window there and laugh before going off to fine-tune what seemed to me to be impossible levels of skill at his or her instrument. I felt like a fraud. I loved music so much, but it all seemed so specific, and my unfocused mind would not permit me to swim in it to the exclusion of other things.

At night, I would go home to my Cambridge apartment and proofread the papers of my Harvard graduate school roommate. She was a socially-minded woman with aspirations of public service in government, and I could see myself in her place. I had just arrived with a degree in international relations from a liberal arts college where I had spent my time writing papers on subjects like government in Zimbabwe and US-Mexican Relations. I was as passionate about studying these topics as I was about deepening my understanding of education, public policy, literature, and different cultures. My interests were not just academic; they were somehow personal.

Then there was music. My spirit and my body depended on it. I had been a listener and a singer for all of my life. I was able to take this for granted until my college band came apart during senior year. School was to end and real life to begin, and it occurred to me that I might not be able to live without being involved in making music, in some way. So I turned down graduate school to become an undergraduate again at Berklee.

It's a little weird to go from weighty class discussions about NAFTA, led by a former-ambassador professor, to the connect-the-dots work of notating a basic bossa drum pattern in arranging 1. But what was stranger for me was to go from forming abstract questions on social, political, and economic issues--thinking about the world--to the immediate little problems of what chord should go next. If I was going to sing, I needed songs, and I wanted to write them myself. This was what I wanted to learn when I came to Berklee. So my focus had to turn inward. Like a shy toddler who can walk confidently but is just learning to put words together, I began to make ragged little gestures that aspired to be songs.

How crucial is self-absorption to the process of making music or any form of art? And when your body is your instrument, and your own psyche is your subject, how do you survive the tedium and narcissism of looking into this ever-present physical-emotional mirror? I'm still the same toddler, but I live in New York City now, writing and performing and trying to "make it" and I struggle with this question every day. I want to find the inward balance of personal discipline and introspection to make good art, but both my life and my art demand that I turn away from the mirror to feel a vital connection to the striving, suffering, dancing outside.

My father Harry Chapin had wrestled with these issues, years before, in a different context at a different time. At the age when I was singing in the James Brown Ensemble and studying jazz harmony, he was a self-taught folkie, writing and performing songs inspired by the message-driven music of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. He went on to find a great degree of commercial success with his own brand of "story songs" about the lives of everyday people. But by the time he hit number one on the pop charts, he had begun to question what, if any, meaning lay in achieving status as a "rock star."

Conversations with my mother and his good friend Bill Ayres deepened his concern over the self-absorption of the 70s, coming so soon after the idealism and social activism of the previous decade. Famines in Bangladesh and Ethiopia were in the headlines, and my dad became especially disturbed over the existence of hunger in a resource-rich world. He would say that hunger was "an obscenity" and that hunger in America was "the ultimate obscenity." In 1975, my father and Bill Ayres founded World Hunger Year (WHY). The name came from the urgency they felt, which told them that every year was world hunger year until hunger was eliminated. A new life began for my dad. The ensuing whirlwind of lobbying, meetings, and appearances combined with an impossibly busy schedule of concerts and recordings only accelerated until he died in 1981.

It's hard to avoid clichés in describing the impact this legacy has had on me, especially the obvious one that my father's short life is "a lot to live up to." And it has been, and remains, a lot. The fact is that I was raised on the idea of fighting social inequities even more than I was raised to make music. But both are in me deeper than any pressure derived from a legacy. And there are contrasts as well as parallels between my dad and myself. So far I have been spared the pressures of commercial success, but not the desire to make some small dent in the injustice of this world and to make things better however I can.

Of course, I am always hoping to make that dent with the music itself, like Pete Seeger with his hammer. Then my sometimes-dueling passions are united in work. Precious are the days when I find a turn of phrase or melody that seems like it might be able to really reach people where they are. And when, in a lyric, I can touch on some of those "outside" things that are so thick in my heart, when I just barely manage to tap on the hurts of the world without being preachy, then, I am happy. But it's an elusive thing. It seems much easier to just get out there and try to help in ways I can see and touch.

For a few years now, I've served on the board of directors of WHY. As time goes on, I find myself getting increasingly excited and more and more involved with WHY's work. I love that WHY looks beyond band-aid remedies for hunger to dig into root causes and empowering solutions. And I am energized to learn how these problems affect us all, and that we all can get involved. Recently, we've been working on launching a program called Artists Against Hunger and Poverty, which aims to establish connections between musicians (and other artists) and WHY's national network of innovative community groups fighting hunger and poverty locally through self-reliance. So far, Bruce Springsteen, Natalie Merchant, and Phish have gotten involved by donating time and concert tickets to groups along their tour routes. They've raised hundreds of thousands of dollars and tons of morale for groups that fight hunger with job training, counseling, after-school programs, community gardens, and so on. Other not-yet-superstars have contributed greatly as well. One of the things I'm trying to do is help get the word out about the program so that we can enlist a diverse array of artists to become members and do what they can.

So I'm still in the practice room with my New York Times, stealing time away from my creativity to try to feel that link to the world. This is part of my essential nourishment, even if it continues to come with a pinch of guilt. It is ironic that I feel bad that I'm worrying about poverty at the expense of rock & roll! It is all wrapped up together in me—the looking in to write songs, the looking out to learn and to work with WHY. Making music and performing can be a combination of both. Now I work to find the balance, and to make these different aspects of my work coherent to myself and to others.

It all makes sense, in a way. Art is the ultimate expression of humanity. When we write a song, or launch into a saxophone solo, or paint a picture, we are sharing with each other our yearnings, our heartbreaks, our spirit. Hunger and the deep poverty that lies at its roots is the denial of humanity. It can rob us of spirit, and take away all aspirations but simple survival. So it is natural to work to vanquish one while exalting in the other—certainly both efforts require much creativity! When I remember this, my work finds symmetry, and my days sing in harmony.

Singer/songwriter Jen Chapin lives in Brooklyn, New York. Her web site is at www.jenchapin.com. For more about WHY and their Artists Against Hunger and Poverty program, visit their website at www.worldhungeryear.org or call (212) 629 8850.