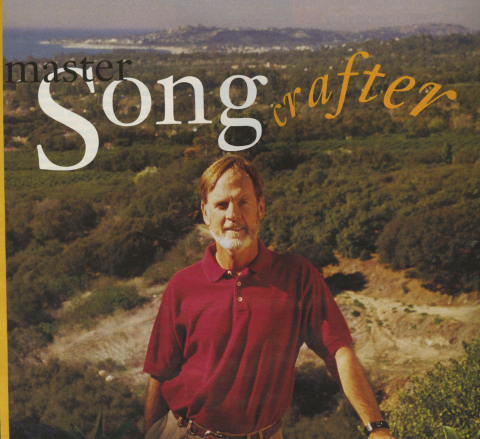

Master Song Crafter

Tom Snow figures he has penned somewhere around 1,000 songs for radio, film, and TV, and now, Broadway. Eight of his songs have earned BMI Million Airs awards, meaning they have been on the airwaves at least one million times. Since the 1970s, his tunes, sung by the likes of Bonnie Raitt, Ray Charles, Barbra Streisand, Selena, Diana Ross, Deniece Williams, Michael Bolton, Dolly Parton, and many others, have topped the pop, r&b, adult contemporary, and country charts. Superstar pairings of Linda Ronstadt and Aaron Neville, Michael MacDonald and Chaka Khan, and Cher and Peter Cetera have also netted gold records and Grammy, Golden Globe, and Oscar nominations singing his music.

As impressive as the list of stars that sing his songs is the roster of writers with whom Snow has collaborated. He keeps company with the best songwriters and lyricists in the business, including Cynthia Weil, Barry Mann, Glen Ballard, Gerry Goffin, Dean Pitchford, and Frannie Golde. Together, they have crafted blockbuster hits like "Don't Know Much," "He's So Shy," "After All," "If Ever You're In My Arms Again," "You Should Hear How She Talks about You," and "Don't Call It Love."

Snow's latest success is with the celebrated Broadway musical Footloose. It is based on the 1983 movie of the same name that contained one of Snow's biggest hits, "Let's Hear It for the Boy." For the stage version, Snow collaborated with Dean Pitchford on nine new songs. The show triumphed in the dog-eat-dog Broadway scene and has had well over 500 performances. Currently, touring companies are taking it to other U.S. cities and to Japan and Australia.

Snow's muse first emerged when he was in third grade in Sarasota, Florida, and he began taking piano lessons. As he matured, he developed a deep love for the music of Cannonball Adderley and other 1960s jazz artists. In prep school, he realized that his romantic notions of becoming a musician were at odds with the path his forebears had followed. He couldn't see himself attending an Ivy League college and then becoming a banker or an academic as they had. Instead, he came to Berklee, earned his degree in composition and arranging in 1969, and went out to seek his fortune in Los Angeles.

Snow is probably the most successful "unknown" ever to graduate from Berklee. To have his name become a household word was not his dream, though. Being a "behind the lines" guy suits him just fine. Yet, the elite in all three nerve centers of the American music scene have duly noted his skill as a master song crafter. Given his demonstrated longevity and the wide musical territory he has covered, it seems safe to predict that even grander vistas lie beyond the next peak for Tom Snow.

Were you interested in songwriting when you were at Berklee in the late 1960s?

"A title gives me a point of view and can suggest a scenario. I'd say that is 75 percent of the battle in lyric writing."

I passed my arranging classes as a senior by writing a song and bringing a chart of it in to be played minus the vocal. I actually put on the first songwriter concert at Berklee. Charlie Mariano [saxophonist and former faculty member] helped out by appearing on the first half. For the second half, my band with [saxophonist] Jay Patton '69 and [bassist] Jeff Steinberg '69, both of whom have done very well in Nashville, sang our songs. It was great fun. That concert is a little bit of Berklee history that people don't know much about. Robert Share and Lee Berk were there and were very encouraging to me after the show.

I was one of the few guys at Berklee back then who was hanging out with the folk crowd in Cambridge. That is where I met Gram Parsons [who later joined the Byrds]. I divided my time between studying composition at Berklee five days a week and then hanging out in Harvard Square on the weekends. It was a little bit of culture clash.

You released four albums early in your career. Did you have hopes of making it as a performer?

Yeah, until I got my head screwed on right. I made my first album for Atlantic with a group called Country. Later, I got hooked up with Peter Asher as my manager and split up the group. I made a second Atlantic album that Peter produced, but it was never released. Next, I made two albums for Capitol, and they didn't go anywhere. I started to realize that my heart wasn't really into putting out my own albums, and I went into writing songs for other people. Right away, that felt a lot easier, and things started clicking.

What was your first song to be cut by a recording artist?

A song I wrote called "You" was cut by Rita Coolidge. That was from my first Capitol album. It brought me to the attention of people like Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil in the songwriting community. Booker T arranged it, Rita cut it in the 1970s, and it turned into a disco thing. It made enough noise on the radio that it got a BMI Performance Award. That got me invited to the BMI party, and then I started writing with other established songwriters.

Do you collaborate with songwriters you've met socially, or are most of your collaborations strictly a business arrangement?

It is more social. I like to have a friendship with a cowriter. It works better if we spend time hanging out and talking. Walking into a room cold is not what I like to do. In Nashville, writers just get in a room and go to town, but they are a collegial group down there. I go to Nashville and do what I call guerrilla writing for certain projects, but that is not the way I usually work.

Your music shows a real stylistic breadth. You have written songs that tap jazz, r&b, dance, and country styles, and now you've written for the stage.

I don't just stay with one style. At one time, I investigated film scoring, got an agent and some jobs. I felt like I owed it to my education and that I wouldn't feel like a grown-up until I did some scoring of orchestral music. I studied orchestration for a year with Albert Harris.

Working in scoring for three or four years taught me that it wasn't what I wanted to do. I like having my time. You spend 10 or more years paying dues to get into the loop for film scoring. When I was working toward that, it seemed like every Fourth of July my friends and family would be off at a picnic, and I'd be in a room staring at the notes. Once you get established in scoring, you can make a lot of money. I just wasn't passionate enough about it to lose the freedom to take off for a few months and go to Europe. The beauty of being a songwriter is that you can work at home at your own pace. My hat is off to film composers like Alan Silvestri. You have to have a tremendous work ethic to do that work.

You have written both lyrics and music for some of your songs. Does one come to you easier than the other?

The music comes easier. I work with lyricists like Dean Pitchford and Cynthia Weil. For "He's So Shy," which I wrote with Cynthia, all I had was the title, and she did the lyric. Nowadays, Dean will just hand me a lyric, and I'll sit down to write the music. I can tell in five minutes whether I'm going to be able to write the music for him. "Ronnie-O" was a lyric that Gerry Goffin gave me, and I sat down and wrote the music just like that. For some songs, I have to really work and rewrite.

Frannie Golde and I have worked together for years. We have a gestalt. She is someone who doesn't know a thing about the technical side of music, but she knows how to come up with a commercial tune. I am always at the keyboard, and she will say things like, "Don't make that chord change, stay here, that was nice." I will want to go some place new, and she will have a different idea.

When you sit down to write, can you feel whether you are going to get something or not right away?

Some days I feel like I might get lucky, but that doesn't necessarily mean that I feel inspired; I just feel like my energy is good. Other days, it can be a struggle. Every day is about going in the room and shutting the door and working. Gershwin said that the first two hours for him involved playing through the dreck to get to the good stuff. For me, it's like getting warm, getting all of the outside noise out of your head, and getting into the space.

I have learned not to take any more credit for the great songs than I take for the really bad ones. Cynthia Weil told me you have to write a really bad song to get at the good one. The idea is to just write and try not to judge it too much.

Do you start by searching out something on the piano, or does a melody pop into your head?

I view writing sort of like chipping away at a block of granite. A lot of times I will start by playing the piano. Sometimes, I will write an accompaniment that is just bass notes; it works better if I don't get too pianistic. I tape everything, so I may listen back to some of it and find an idea that has potential.

For a lot of the songs that I wrote in the 1980s, I would find a drum groove and try to find a signature bass line that was melodic in its own way and had some cool characteristics. Then I would let the groove dictate the rhythm of the melody so I could find the length of the phrases and the rhythm of the phrases. I am learning that in a lot of music, the space that comes after a phrase gives you a chance to comprehend that phrase.

If I have a title in mind, that is a big help. A title gives me a point of view and can suggest a scenario. I'd say that is 75 percent of the battle in lyric writing. I love setting music to written words. It is a challenge to find the rhythm of the lyric.

How do you work through the pacing of the lyric once you have the point of view? Let's say you have two verses before the chorus comes up, and then you need a third verse. How do you continue the scenario and not just say the same things again in a different way?

Ah, yes, the second act. I studied screenwriting once because I was working on films. Everyone can write a first act; it is the second act that's hard. You can write a great first verse and a great chorus, and then the work starts. You don't want to be redundant. In pop music, you can't get too story-oriented like you can in country. In pop, there really aren't stories; it's more vague stuff about love and being young. If you listen to the Backstreet Boys, they are not really telling stories. They are talking about these emotions. You find songs saying things like I want it my way or what is the meaning of being in love. It's inner teen angst.

Is it hard for you to go there in your writing these days?

Sure. I am 52; that's not my life. If this is your chosen career, it's not practical to go into a room and say I'm only going to write what I want to write. Songwriting will become an avocation then because you won't get your songs cut. These are some of the realities of the kind of songwriting I do. I work behind the lines. I'm not trying to be a recording artist. I am writing for the market. It makes no sense for me to write things that are totally idiosyncratic. At the same time, you have to let a little of that into your writing. That is what distinguishes a good pop song from the ordinary schlock. There can be intelligent pop lyrics that take people in.

You still seem to connect in the youth market though; you had a cut on last year's Christina Aguilera CD.

When Frannie Golde and I wrote "So Emotional," I never thought that it would work, but it did. You have to be flexible if you want longevity in this business. I've been doing this for 30 years.

What was involved in creating the Broadway musical Footloose?

The movie Footloose came out 14 years before the show, so we had to take the hit songs, like "Let's Hear It for the Boy," and make them more theatrical and still retain the qualities that made them hits. We also had to add new material that would fit. We rewrote six songs from the film, two of which were mine. Dean Pitchford [coauthor of the show] rewrote the lyrics. We changed things around and expanded the little-known song "Somebody's Eyes," to make it a major piece in the musical. We also wrote nine new songs. We began working on the show in 1994, and it opened October 22, 1998.

It must be a herculean feat to get a show up on Broadway.

It is very hard, the hardest thing I've ever done. Writing for Broadway is a very rarefied field; not many people are doing it. You have to really love the idea of your show and be willing to go down in flames for it because chances are, you will go down in flames. It takes about five years of your life to see the show go from the germ of an idea to the realization onstage. We went from spending 10 hours a day in a little room creating for six weeks to working with choreographers, dancers, and musical directors. I love collaboration, and working in musical theater is the most collaborative form there is. The whole give-and-take was just sensational; you become like a family.

The chances of having a hit on Broadway seem much more remote than those of having a hit record.

Critics from the New York Times and other papers just savaged us when this play opened. They were relentless in their attacks, they hated it so much. But it didn't matter. They really tried to close us down. It was almost like a campaign. They had a real ax to grind. We weren't expecting to get great reviews, but none of us expected that. We got lots of good reviews from the secondary press, but the theater elite really hated us. It made them apoplectic that we continued to succeed in the face of that. The show is a bona fide hit on Broadway, and that is very rare. We must have done something right.

Is this the kind of project you would attempt again?

I loved the level of creativity, talent, and dedication of the people involved. I would be crazy enough to go through it all again because it is so stimulating, so big. It is refreshing to walk in to work with people like the actors, the set designers, and all of the teams who work at such a high degree of professionalism.

I didn't like the viciousness or the pettiness that is part of the Broadway scene. There are people who want you to fail, and you have to learn to deal with it.

Your songs seem to have a long shelf life. Bill Medley released "Don't Know Much" as a single in 1981, but it wasn't a hit until 1989 when sung by Linda Ronstadt and Aaron Neville. "You Might Need Somebody," another older song, became a European hit for Shola Ama in 1997.

That hit for Shola came out of the blue. I had nothing to do with it. The song was a hit for Randy Crawford around 1982. Shola's

management loved the song and thought it was perfect for her. It never hit here, but it did in the U.K., France, Germany, and Israel. By then, the song was 18 years old. On my demo album, I have both versions. The one by Joe Walsh is how the original went.

Do you think if you were approaching the business now as a younger person, you would find it harder to break in?

I really don't know. In some respects, if you were to factor in a modern Berklee education as opposed to what was available for songwriting when I was there, I think I would be more prepared. Also, music isn't coming so much from the streets anymore; it is a lot slicker. That is sad in some ways, but in other ways it also makes the vocabulary much more available to the young writer.

For me, I came out to Sunset Boulevard in the summer of 1969 from a prep school upbringing and a buttoned-down Boston jazz school education. It was something else. Now, I'm not so sure that there is so much difference between the educated and uneducated approach to writing. Everything is so homogenized. In some respects, I feel that music lacks real personality these days. But back then writers who were the age that I am now said the same thing about the music I was writing.

One thing that impresses me about the young writers coming up is that they are so professional right off the bat. In terms of personal responsibility, having a professional approach, and knowing the kind of effort it takes to write a hit, I feel I didn't understand all that until I was about 29.

What would you tell people who are just starting out in a songwriting career?

Being a behind-the-lines guy as opposed to being an artist who is out front, I would tell them to approach songwriting as a craft, and you learn a craft over a period of time. I actually don't think it can be taught; it has to be learned in the marketplace. You also learn a lot from the people you work with, so get in there with the best, people who challenge you. If you need to collaborate--most songwriters do--there might be relationships where there is a little friction. That can create a spark that produces a flame, and that can be good. You have to challenge yourself and not just sit back in your comfort zone. You have to go places where you need to find your way. Sometimes you fall on your face, but you learn.

I would also say, don't make a career of going to songwriting seminars. I used to speak at those, but I would see the same faces showing up. That's not to say that you can't learn something there or that you can't learn about writing a lyric from books. Actually, I am quoted in some of those books. Whether you go to Berklee and learn about traditional harmony and so forth or not, a lot of it comes down to understanding what choices to make and having the instinct to make them at the right time. That applies to any art form.

What makes the difference between a song that is a smash for six weeks and one that makes some noise and then is never heard of again? A guy can hit a homerun, or, by being three millimeters in another direction, he can hit a pop-up to shortstop. It is the same in writing songs. There is such an economy there. Songs are little microcosms. It is not like writing a long through-composed work; you have to get to the point. Don't bore us, get to the chorus.

There is no room for error in such a short piece. A person's attention span is about 20 seconds long, and you have to be able to reach them right away. These are things that a songwriter like me has to think about. Sting can come out with a song like "Brand New Day," and it will be a single and get enough promotion and airplay until it takes hold. If I wrote a song like that, no one would cut it. I'm not taking anything away from that song; it is a good song, but it wouldn't get a songwriter like me anywhere.

The type of writing I do is not necessarily meant to be a great personal statement. My objective has been to write good songs that will appeal to people and that can be sung by a number of different artists. If you are James Taylor or Sting, it is different. They are the vehicles for their own writing. As the artist, you are speaking about your innermost feelings. I have to consider more than that. Again, it is a craft. Don't confuse the two or get this notion of yourself as an artiste who has to tell the world everything in your heart.

As a songwriter, you are an independent contractor. Essentially, you are responsible for making things happen, so you have to develop real discipline and go after it every day in one way or another. You need to understand that you are writing for a marketplace that is ever-changing, so be real, learn the craft, and be flexible. When you collaborate, you need to check your ego at the front door and be really open. For kids who come out of Berklee with a real education, it is easy to work with someone who doesn't have a music education, but is a good writer. That is the kind of collaboration that can really happen--especially with lyricists.

Coming to the business with a degree in composition like I did gives your writing diversity and your career longevity. It has come in really handy for me.