The Woodshed: Writing a Canon

Beth Denisch is a professor in the Composition Department. She is an internationally recognized composer whose works have been recorded and performed worldwide.

“Canon” means rule, or law, and in music, the simple canon uses a very strict rule to define itself. Canons are like the children’s game “Follow the Leader” where the leader makes a move and the follower imitates what the leader does. In a canon, the follower voice sings the same music as the leader voice beginning anytime after the leader has started but before the leader stops. When the follower voice sings exactly the same as the leader voice, the result is a strict canon. But when the follower voice makes any minor adjustments, it is called a free canon. Canons can be written for three, four, eight, twelve—any number of voices.

Rounds

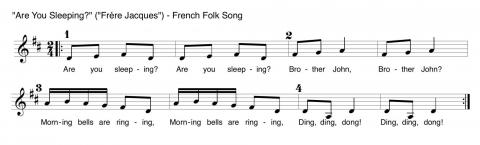

One of the simplest forms of a canon is the round. They are found in many folk traditions and children’s songs. A round is called an “infinite canon” because as soon as you get to the end, you go back to the beginning. For example, in the traditional French favorite, “Frére Jacques” (see example 1), the numbers above the staff indicate that this round is for four voices. Each number tells the corresponding follower voice (voices 2 to 4) when to begin singing the melody in relation to the leader (voice 1).

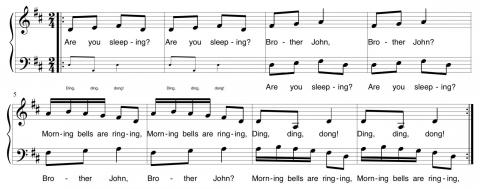

Example 2 shows the round written out for two voices using the second vocal entrance of the round for the follower voice. The follower voice begins at the downbeat of measure 3 (see the first full-sized note in the bass voice), an octave below the leader voice. The distance between the first note of the leader voice and the first note of the follower voice defines the interval of the canon, in this case, the octave. This is an infinite canon at the octave. It should be noted that composers write canons at other intervals as well.

Consider the harmonic implications of this “Frére Jacques” setting. Most of the resultant intervals are consonant, implying the tonic chord, while the notes A and G, appearing with the words “bells are,” may imply the dominant-seventh chord. Traditional European-based rounds like “Frére Jacques” usually stay close to the tonic and sometimes dominant harmonies.

“Ah, Poor Bird,” example 3, has a different sound; it’s more modal than tonal. Notice how the harmonic implications often refer to the relative major (F Major) and the minor dominant (a minor).

Example 4 shows “Ah, Poor Bird” as an infinite canon at the octave using the third vocal entrance for the follower voice.

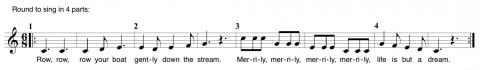

“Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” another well-known round, is more similar harmonically to “Frére Jacques” than it is to “Ah, Poor Bird.” In example 5, it is written as a round for four voices.

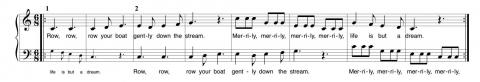

Example 6 shows “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” written as an infinite canon at the octave using the second vocal entrance for the follower voice.

Adding a Cadence

When a canon has a cadential ending, it’s no longer a round or an infinite canon. You could say that it has become a finite canon, as seen in example 7 where “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” comes to a close at the end of the phrase. The canonic treatment in this counterpoint example ends in measure 6 and the phrase closes at measure 8 with a perfect authentic cadence. The perfect authentic cadence (PAC) is a strong and frequently used formula found in many styles of music, but is idiomatic to classical styles. In a PAC, the harmony resolves from V to I with the treble voice ending on the first scale degree (often approached by step) and the bass voice using the roots of both chords, moving from scale degree 5 to 1.

Writing a Simple Canon at the Octave

What follows are nine steps for writing a canon at the octave.

Step 1: Set It Up. Choose the length, meter, and key. For this example, we will create an eight-measure canon in 4/4, in the key of F major.

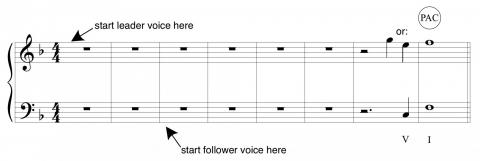

Step 2: Outline the Form. After the leader voice begins, the follower voice enters two measures later. Both voices stop at the downbeat of measure 8 where the bass voice moves from scale degree 5 to 1 and the treble voice steps to the tonic for that traditional PAC sound. (See example 8 on page 26.)

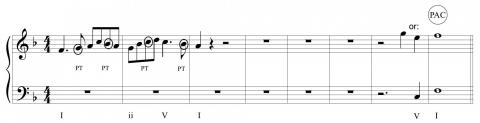

Step 3: Write the beginning of the leader voice. Write a simple diatonic melody for measures 1–2 (phrase a) that clearly outlines tonic-dominant-tonic harmony. Establishing the key is very important in all tonal music. Label all non-chord tones. In example 9, the non-chord tones are all passing tones and are labeled PT or DPT (for double passing tones). It’s important to be aware of the harmonies implied by the melodies you create. Analyze your harmonies and include Roman numerals under the bass clef or chord symbols above the treble clef (even when only the leader voice is playing).

Step 4: Start the Follower. For this exercise, we will keep all notes diatonic to the key. Copy measures 1–2 of the treble voice (phrase a) into measures 3–4 of the bass voice transposing the notes down an octave. (See example 10.)

Step 5: Continue the Leader’s Counterpoint Against the Follower. Write good counterpoint in the treble voice in measures 3–4 (phrase b) to go along with the existing music (phrase a) in the bass voice in measures 3–4. (See example 11.) Use mixed ratios to complement the melody in the bass voice. Mixed ratios happen when different note values occur simultaneously in the two voices. Varying rhythmic ratios and adding syncopation between the voices helps maintain melodic independence for each voice and is an important aspect of well-written counterpoint. Make sure the new melody supports the implied chords and label the non-chord tones.

Step 6: Continue the Follower Voice at the Octave. Copy measures 3–4 of the treble voice (phrase b) into measures 5–6 of the bass voices transposing the notes down an octave. (See example 12.)

Step 7: Continue the Leader Voice. Write counterpoint in the treble voice in measures 5–6 (phrase c). Once again, use mixed ratios to complement the melody in the bass voice. Make sure that this new part of the melody supports the implied chords and label non-chord tones, as shown in example 13.

Step 8: Continue the follower voice and prepare to cadence. The next logical step would be to copy measures 5–6 of the treble voice into measures 7–8 of the bass voice transposed down an octave. We would do this if the canonic part of the composition were longer than eight measures. However, we need measure 8 to be the downbeat for the resolution of the PAC, so we must end the canonic passage before that point.

Start copying phrase c into the follower voice. At some point, you will leave that melody and make the cadential formula to close the phrase. In this example, we will copy the leader voice from measure 5, beats 1–2, into the follower voice in measure 7, beats 1–2 (down an octave). So phrase c begins in the follower voice, then departs from the canonic material to prepare for the cadential formula. (See example 14.)

Step 9: Create the cadence. Fill in the rest of measure 7 to make the PAC. The canonic passage ends with new counterpoint that realizes the cadence (see example 15).

Ex. 1

Ex.2

Ex.3

Ex.4

Ex.5

EX.6

Ex.7

Ex.8

Ex.9

Ex.10

Ex.11

Ex.12

Ex.13

Ex.14

Ex.15

An Afterthought

Hey, Solo gigs are great, and I'm never late for rehearsals!

The canon is one of the most important elements in counterpoint. It is musically powerful when previously heard material reappears later in another voice, as in a canon. Imitative counterpoint is a larger set of compositional techniques that includes the canon. In this type of music, both voices maintain independence by simultaneously employing different rhythms, pitches, or melodic directions. However, they sound like they belong together because they’re doing the same thing, just at different points in time. This simultaneous contrast and delayed repetition is crucial to understanding counterpoint.

My book explores many more techniques for working out musical ideas to transform a creative spark into an effective piece of music in almost any style. Congratulations on expanding your musical horizons to include counterpoint!