When Opportunity Knocked

It’s often said that success happens when preparation meets opportunity. Keith Harris has proven the theorem. When opportunity knocked with a shot at becoming the drummer for the Black Eyed Peas, Harris was prepared and remains ready for new challenges that continue to come his way.

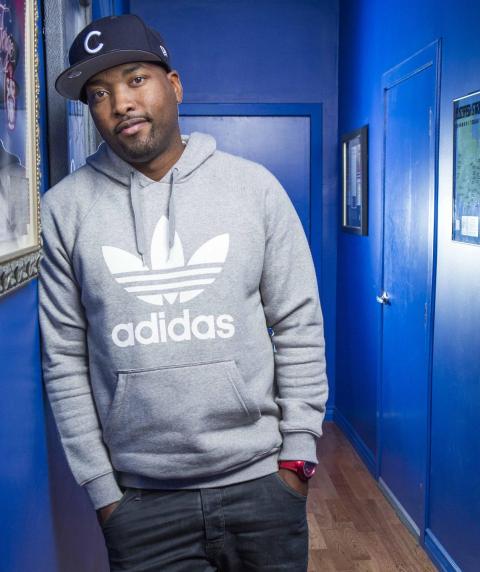

Keith Harris '98

Joey Cobbs

His kaleidoscopic musical career has taken him from humble beginnings drumming with the band at New Friendship Baptist Church on the South Side of Chicago to gigs at the Super Bowl, the World Cup, and stadium concerts across the globe with the Black Eyed Peas. In addition to extensive touring (Harris’s travels have filled three passports so far), he’s also much sought-after as a music director and in various roles in the studio. He was a cowriter or producer on four tracks from the Peas’ 2010 Grammy-winning album The E.N.D. (Energy Never Dies). He’s also written or produced tracks for stars including Madonna, Robin Thicke, Usher, Mary J. Blige, Busta Rhymes, and many more. His cowriting on Estelle’s song “American Boy,” netted him a Grammy in 2009, and his production of the Revival album by Canadian R&B artist Jully Black paved the way for the record to win the Best R&B Album category at the 2008 Juno awards.

Harris has collaborated on various projects with Peas vocalists Fergie and will.i.am (whom he simply calls Will). Will.i.am offered opportunities for the multitalented Harris to assist with writing and production chores and to play drums, keyboards, bass, and other instrumental parts for movie soundtracks and various recording projects—including Michael Jackson’s 2008 release Thriller 25. In 2014, Harris cowrote will.i.am’s single “It’s My Birthday,” which topped the charts in the United Kingdom. More recently, Harris cowrote and produced the single “Life Goes On” for Fergie’s new album, Double Dutchess. He currently drums and serves as Fergie’s musical director for the singer’s one-off live dates and tours.

When we met at Harris’s North Hollywood production studio in mid-December, he had just returned to Los Angeles after appearances in New York with Fergie on the NBC Today show and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Harris was back in town to spend Christmas with his wife and their two-year-old son, and to finish up production of backup tracks for the Backstreet Boys: Larger than Life residency show at the Axis at Planet Hollywood in Las Vegas. A week and a half later, he flew back to New York for an appearance with Fergie on Dick Clark’s Rockin’ New Year’s Eve 2017.

While at home, Harris said that he hoped to find time to get to a movie theater to see La La Land, in which he had a small role. He hadn’t seen the completed film yet. Well before the movie collected seven awards at the January 8, Golden Globe Awards, Harris was hopeful that it could open doors to more film and TV work—acting or scoring.

Harris came to Berklee with dreams of becoming a touring musician, but he majored in music production and engineering as a fall back. His finesse in each area, amiable personality, and capacity for hard work have prepared him to succeed admirably in both. Harris cites Quincy Jones as the archetypal contemporary musician and aspires to a career course following diverse musical tributaries and reaching high-water marks Jones has. But Harris is wise and patient enough to know that such things can only unfold organically.

“I just let the natural progression happen,” he told me. ”I keep my positivity meter up and my prayers going.”

You have said that Henry Jones, a drummer who played in your church in Chicago, was an important figure in your development. Can you elaborate on that?

I grew up in a single-parent home; my mom raised me, and I learned a lot at my church about discipline. Henry taught me to play the drums with discipline. He took me under his wing, but he never gave me a lesson; he just told me to watch him. He gave me pointers on posture and how to hold my hands, and to be aware of what was going on with the musicians around me. In gospel music, you might start a song as a waltz then go into a rock groove and then to a Latin feel. Henry helped me learn to dissect all those things and always be aware of what was going on around me. I still talk to him to this day. I’m someone who made it out of the South Side of Chicago. There was an amazing amount of love and encouragement in my church.

When did you learn the vocabulary of music?

I went to the Curie Metro High School for the Performing & Technical Arts and learned to read music and write charts and arrangements there. At that time, Studio Vision [software] for sequencing was new and the school had that plus keyboards, synthesizers, and V drums. I developed a love for programming and sequencing in my junior and senior years there. It all flourished when I got to Berklee.

Did you know that you wanted to major in MP&E when you came to Berklee?

Yeah. I felt that I knew how to play drums and that I’d get more experience playing, but I wanted to have a plan B in case becoming a touring musician didn’t work out. I met Richard “Younglord” Frierson, who was a producer for Bad Boy, at a clinic at Berklee. Students were playing him their songs and I played some of my beats. He liked them and stayed in contact with me. While I was still a student, he would bring me down to New York to work with him.

Were you engineering or making beats for him?

At first I was engineering. Back then he wasn’t using computers; he was working with the MPC 3000 [sequencer-sampler]. As we worked at his house, I would catalog where the MIDI cables went, the program numbers for each keyboard, and what effects we used so that when we went into the studio we could recreate everything. I learned a lot about producing from him.

You’ve said elsewhere that he impressed upon you the less-is-more concept.

Yeah. At Berklee, you get a wealth of musical knowledge, and if you go into the hip-hop world you can try to put in too much information. So I had to take the sevenths and sometimes even the fifths out of the chords. It wasn’t what you played as much as it was how you played it. Even when playing drums live, it’s more about having people feel it more than you spewing out information that they won’t understand.

How did you initially connect with Printz Board, keyboardist for the Black Eyed Peas?

I met Printz through [guitarist] Adam “Shmeeans” [Adam Smirnoff ’99], a friend from Berklee. He hit me up to cover a gig with a group called Star 69 that Printz was working with in New York. [Printz] started singing my praises when he went back to L.A. About two weeks later, he called me about playing with the Black Eyed Peas for three months during the summer.

Before that, I had been working with Frierson in New York and going back to Boston to work with my cover band that played all over New England and then driving back from wherever I was to Boston on Sundays to play with the band at my church. I did that for three years. All of that driving prepared me for the Black Eyed Peas.

What year did you start with the Peas?

It was 2003, as they were rising. At some of the first gigs we had only 50 people there. To see things go from that to playing the Super Bowl, the World Cup, Ipanema Beach in Brazil to more than 100,000 people has been crazy.

In our first year, we did more than 500 shows—sometimes two or three a day. We’d play on the Good Morning Arizona show, then go and open for Christina Aguilera and Justin Timberlake. We also did our own club shows. We were everywhere all the time. By then, my body was prepared for all of the travel, learning to sleep anywhere or stay awake, and being in confined spaces for long periods of time.

How did you progress from being the Peas’ drummer to cowriting the group’s material?

The four band guys had laptops so we could work on songs on the bus in our bunks or in the bus lounge and in the dressing rooms at the venues. Printz Board was the keyboardist, George Pajon Jr. was the guitarist, and Tim Izo [Orindgreff] was a utility man playing everything. I understood that those relationships existed, so when I came in, I was careful not to infringe on anyone’s work by telling people all the things I could do. In time, will.i.am heard that I made beats and played keyboards and invited me to the studio to play the stuff I’d been working on. He liked what I was doing.

Printz played keyboards one way and I played more in a gospel style. Adding those flavors to the albums Monkey Business and The E.N.D. gave a different energy than previous records had. I think it was really cool that they guys who played the shows were also writing for the records. We were all on the records that won awards.

Let’s talk about the different types of songs you cowrote for the Peas. “Imma Be” has just one chord in the first section, then the tempo picks up and the final section has a string of chords over a bass line. What parts did you come up with?

The first half of the song was mine and I sent it to Will. He told me where he wanted the tempo to speed up to 117 bpm. Then he said, “Take the chord progression from the B section of Michael Jackson’s ‘Can You Feel It’ and play it backwards and send it to me.” Will gives me some crazy things to do and I help to make sense of them musically. All of his directives resulted in that song. That was the biggest song I’d written up to that point. I felt from the beginning that it was a hit—in fact I named the Pro Tools session “Hit.” I felt it, and it turned out to be a number one.

“Meet Me Halfway” has melodic sections alternating with rap sections. Can you break down your contributions to that one?

I got the chord progression for that song in a dream. It’s a very emotional chord progression and I love what Jean Baptiste wrote for the top line. It’s a special song and another that went to number one. The ending was my ode to Cold Play and their song “Viva La Vida.” The soundscape at the end of that song inspired me. I wanted “Meet Me Halfway” to sound bigger than a beat, to have an orchestral feel.

“All That I Got” is pretty much a straight-ahead R&B ballad.

Yeah, I sampled the song “Zoom” by Lionel Richie and the Commodores. I did that beat in 1998 when I was working with Richard Younglord Frierson. Fergie recorded it on her first solo album five years later. A good song never dies. I wrote it in 1998 and it wasn’t recorded until 2003. It had to find the right marriage with the top line.

Keith Harris '98

How did your work on other projects begin?

My first opportunity with Will was for the movie Poseidon in 2006. We cowrote “Won’t Let You Fall,” the song that Fergie sang at the end of the movie. I also played piano on it. In the early days, things came my way from me being Will’s utility man playing whatever he needed: keys, bass, vibraphone, or arranging strings. I became a resource to him by being available to do all jobs when called upon. Since I was an engineer, as we worked I learned what sounds he liked. I made his job easier and enjoyed getting to be part of his projects. I was also able to communicate to the other musicians in ways he couldn’t. He couldn’t arrange horn parts, but he’d tell me what he wanted and I could translate it. Our relationship grew over the years. Will and I worked in the studio with Michael Jackson, and James Brown worked with us on the Monkey Business album. I’ve gotten to work with some of the greats.

What was the first project you did on your own?

I got my own management in 2011, and through them I got to cowrite the song “Gang Bang” with William Orbit and others for Madonna. Now people come to me for all of the things I do, including being a musical director.

At first I felt I didn’t need management because my work was coming through the Peas. The train was rolling, but when I wanted to expand and meet new artists, I needed a hand to reach further than I could. Helen Yu [music attorney] and AAM [Advanced Alternative Media Inc.] got me some projects. Now I am working with Melvin Brown, who worked closely with Johnny Wright, who managed the Backstreet Boys. I met Johnny when the Peas were playing a Justin Timberlake tour. He has seen me grow from just a drummer to a producer and has taken me under his wing. You definitely need to have the right people around you who believe in your talent and vision.

When you write, do you always make the beat or do you do top lines, too?

At Berklee I used to write a lot of top lines, but now I work with the top line writer on melodies and guide them with the concept for the lyrics. I let the writer put the concept into a story.

How do you start the writing process? Do you come in with an idea or come in cold?

It depends. Sometimes you hunt and come up with something. Other times a writer may come in with something and I’ll put the music to it. A lot depends on the session, who you’re working with, and how comfortable you are with each other. Sometimes we will write from scratch. I’ll come up with some chords and the other writer will come up with a top line. We’ll build it from there.

What kinds of things are you working on currently?

Right now, my phone is ringing about musical directing. I hadn’t thought about doing that until about four years ago. My first gig as an MD was with Cheryl Cole, an artist from the U.K. She and Will had a big song called “3 Words.” I did prerecords for her Million Lights tour [2012]. She didn’t have a live band, so I made prerecords to sound like she had one. I recorded and mixed everything in L.A. and then went to London to make sure everything ran properly. I get calls [for prerecords] from artists who aren’t going to take a band out on tour. I’ve done that for Estelle, Fifth Harmony, Miguel, Will, and Fergie. I am currently working on prerecorded music for the Backstreet Boys for their residency in Las Vegas. I was the music director for their 20th anniversary tour. So I bounce from being a musician to producing depending on what’s hot at the time. It’s a good way to have variety and a consistent income.

In a given year, what types of projects might you take on?

February is awards [month] out here. You have the Grammys, the Super Bowl, and the Oscars all happening around that time. People need bands for parties, and Fergie may perform somewhere and I’ll go to do that. In March and April people are preparing for summer tours. Then if you go on the road, that will last through the summer into September. In December there are the Jingle Ball shows in L.A., New York, and Boston. When the Peas were on the road a lot, that is how the schedule went.

What are the Peas up to these days?

Everyone is doing their own separate projects, so the band is on hiatus. We’ve been in production mode. I cowrote and coproduced Fergie’s single “Life Goes On” for her new album Double Dutchess. I’ve been doing some one-off gigs with her, and once the album drops we’ll be in full tour mode. I will play drums and be her music director.

Do you expect to be doing long tours at this point?

Fergie will do some long stretches with a pause because she has a family now. If Will had his way, [the Peas] would have stayed on tour since 2003. We did a straight 10 years of touring. If you add up all the dates, we might have had three months off in 10 years. We worked all the time and it paid off. When you’re building something you have to stick it out.

The fans have been waiting on Fergie’s new solo album and a new Black Eyed Peas’ album. They are pretty loyal. In 2015, the Peas had been together 20 years. At that point we should have been on the road, but life circumstances changed that. I’m thinking one day we could have a Vegas show if Will would let that happen. A band can do three months there playing five nights a week, no traveling. I would look forward to that one day. But we will go on tour again and I am super excited about getting the troops back together.

How did you come to have a role in the movie La La Land?

I have a musicians' agency called the Gobo Music Agency or TGMA. A friend, Mike Jackson, works with John Legend, who is also in the movie. Mike called me asking if I could recommend some musicians for the movie. They were looking for a couple of background singers and a drummer. I said, “If you don’t mind, I’d like to nominate myself to be the drummer.” I sent my bio, video, and pictures, and they wanted to use me. I got together with the costumers so they could see my style, and they cast me as myself in the film. I have some lines in a scene with Ryan Gosling. My character is supposed to be Ryan’s friend from years ago and we meet up again. I’m not an actor; I’m just being myself in the role. Ryan made me feel really comfortable on set. It was a really cool experience.

[Editor’s note: Keith’s speaking parts were not included in the final cut of the movie. But he appears in a handful of scenes playing drums in a band that features Ryan Gosling and John Legend.]

Damien Chazelle, the producer, is a drum enthusiast. He got me this huge drum set for these scenes. There were about seven toms, 13 electronic pads, chimes, and cymbals. He wanted me to hit everything and do crazy stuff. It was the first time in my life where I was told to play more! A lot of my friends are in the movie. It was cool that they used real musicians so it would look natural.

This is the second movie I’ve been in. I was in Be Cool with the Black Eyed Peas. I also did some scoring on Freedom Writers with Will. I also did the theme song for Madea’s Big Happy Family. I want to pursue a SAG union card. In my life I’ve had a great variety of opportunities.

You’ve been riding the wave for a while.

I’m glad the wave is still going! A lot of times it ends after 10 years. It’s been 14 years since I joined the Peas. Everything took off with the information I got at Berklee. I feel I had an edge over other musicians out here who do what I do. MP&E, counterpoint, ear training, it all comes out when you need it. I’d tell young Berklee students not to take any classes or instruction for granted. Being able to write a drum chart is what helped me get the gig with the Peas. Because I had to learn so many songs so fast, I just wrote charts. Someone who couldn’t write a chart would have to put themselves under a lot of stress to try to memorize everything so quickly. All the tools of the trade helped my career.

I feel very blessed to have gone from playing drums at church to being a two-time Grammy-winning producer, songwriter, and musician. It’s only when I do an interview and look back at my career that I see what I’ve I worked on, and think, “Wow, I did a lot of stuff!” When you’re going through it you don’t really see it. Everything flew by so fast. I hope the next 20 or 30 years will bring more accomplishments.

Can you give me a parting shot?

Yeah. I formed some of the best relationships of my life at Berklee. The education and the faculty members were really great, and the relationships that you make there last a lifetime. The people you meet at Berklee will be in the workforce. There are about 50 people from Berklee out here that I stay in touch with. You’ll make a connection with one or two people at Berklee who can put you where you need to be. It was my friend Shmeeans who connected me with the Black Eyed Peas. That changed my whole life! That’s something Berklee gives you that you can’t put a price tag on.