The Woodshed: Forrest Gump Turns 20

Top Film composer Alan SIlvestri ’70 shares insights about one of his most memorable scores.

Alan Silvestri ’70 has penned music for more than 90 feature films, including The Croods; Red 2; The Polar Express; Romancing the Stone; The Avengers; Cast Away; Back to the Future I, II; and III, Contact; The Bodyguard; Flight, and more. He is currently scoring Run All Night starring Liam Neeson.

Phil Farnsworth

July 2014 marks the 20th anniversary of the release of the blockbuster movie Forrest Gump. The film swept the nation and the Academy Awards, winning six Oscars, including one for best picture. With an engaging storyline, an all-star cast (Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Sally Field, Gary Sinise, and Mykelti Williamson), plus amazing visual effects, the movie connected with audiences in a big way. Alan Silvestri’s iconic orchestral score was integral to the movie’s emotional appeal. Sometimes sweeping, sometimes introspective, Silvestri’s themes plumbed the emotional depth of both the characters and the storyline, assisting director Robert Zemeckis in telling the fantastic tale of an endearing Alabama native with an IQ of 75.

As the film opens, a feather falls lazily from the sky above Savannah, GA, and wends its way to earth ultimately coming to rest against Forrest Gump’s muddy sneaker. Accompanying that scene is Silvestri’s memorable theme played delicately by pianist Randy Kerber and orchestra. Silvestri’s simple melody, diatonic harmony, and light orchestration set the stage for what will unfold as Tom Hanks (as Forrest Gump) narrates the story of his life to whoever happens to sit next to him on a park bench as he waits for a bus.

In a phone conversation from his home in Carmel, CA, Silvestri shared details about composing the movie’s wistful opening theme. “I wrote it in about 15 minutes,” Silvestri says. “But that’s not always how these things go. Bob [Zemeckis] asked me to come to his cutting room in Santa Barbara to see the opening sequence where a feather floats down from the sky. Then he said, ‘So the music just needs to be something that expresses the essentials of the entire film.’ He’s never shy about wanting it all! Bob is a great human being with a tremendous work ethic, and he makes everyone want to bring him their best game.”

The next morning Silvestri sat at his upright piano searching for the notes that would get to the film’s essentials. “I had to communicate the innocence and childlike character of Forrest,” he says. “That led me to think I needed to write something like a nursery song. I started plunking around and soon came up with the melody. It seemed to be a gift that dropped in my lap.”

Silvestri made a simple electronic mockup of his theme and visited Zemeckis again. “He really liked it and asked his editor to put it in with the footage,” Silvestri recalls. “From then on, whenever they previewed the movie for anyone, that mockup would play.” Silvestri left the meeting confident that he was on the right track. “I thought, ‘I get this movie. Bob loves the theme, this is the material for the whole thing.’ But when I started working on the next cue, that theme didn’t work with it. I kept pulling it out for every other cue after that and it never worked! At this point we were thinking of it as the theme for Forrest Gump, but it was really “The Feather Theme.”

After the film’s opening scene, Silvestri’s “I’m Forrest . . . Forrest Gump” melody isn’t heard again until the final scene when the floating feather motif reappears as Forrest watches his young son board a school bus at the same rural location where his mother launched him on his first day of school. “It was interesting,” Silvestri recalls, “at the end of the film—even after all Forrest had been through—he wasn’t any different. So that theme was still appropriate for him at the end.”

Cinematic Scoring

Silvestri sets his theme in the key of G and opens with a two-note ostinato figure played in the left hand on the piano and doubled by the harp. (See the full score to “I’m Forrest . . . Forrest Gump.”) The ostinato continues for the first 38 bars of the cue, making slight pitch adjustments to fit the changing chords. The violins enter at bar one playing a sustained high D pianissimo through the first 12 bars continuing as the piano melody enters in bar 4. Silvestri set the piano melody in a register above the staff, enhancing its children’s tune quality. The violas, cellos, and basses enter in bar 13, also at a pianissimo dynamic level, adding dimension and motion with slow-moving inner lines. The 16-bar melody is repeated starting in bar 20, but played an octave lower on the piano as human activity on the ground is introduced on the screen.

For Silvestri, the feather set the stage for the film. “The feather comes out of the sky as Zemeckis is showing this beautiful town,” he says. “After it passes over a pedestrian’s shoulder, it’s on the way to Forrest, and I modulate to a new key following what Zemeckis was doing cinematically. Because of the nursery-song nature of the tune, I didn’t want to introduce new material—there is no B section to ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat.’ The modulation allowed the tune to be played again while giving a sense that it had gone somewhere.”

Before the modulation, a fragment of the melody makes cameo appearances in the flute (bars 35 to 36) and clarinet (bar 37) as the ostinato continues. Following a glissando on the harp (bar 38) Silvestri’s unprepared modulation up a minor third for the melody’s third appearance in B-flat gives the cue a big lift. At this point, the ostinato pauses as the strings take the melody, while French horns and tuba add color and drama. The piano recedes to the background playing only light fills (bars 42, 46-48, 50 to 52).

“The intimate aspect of a cue in a main title can set the tone for the film,” Silvestri says. “But this is a big film, and bringing the orchestra in at that point gives the audience a sense of the size and scope of what’s to come. It’s not a film that takes place on a park bench, it has tremendous themes: war, love, life, and death. So this sweet piano tune is taken over by the orchestra. It’s pretty, but it’s rich.”

Just as the feather is arriving at Forrest’s shoe with the theme playing in the new key, the first and second violins transform from playing the melody in unison to playing in sixths (bar 47). The sound of the sixth intervals adds poignancy as the audience forms its first impression of Forrest. As he picks up the feather, the scoring becomes sparse. A single glockenspiel note in bar 53 coincides with the reappearance of the ostinato (played only by the harp this time). The string texture diminishes as the cellos and basses drop out in bar 55 leaving the violas, and violins sustaining a quiet pedal point on the root and fifth of the key. The piano, the theme’s main voice, regains prominence with final fills (bars 65 to 68) played by the right hand alone over sustained whole notes in the strings.

When the theme returns under the movie’s final scene, it’s a slightly shorter version of the section in B-flat. A wind lifts the feather from the ground by Forrest’s shoe and wafts it heavenward until the screen goes dark.

Other Prominent Themes

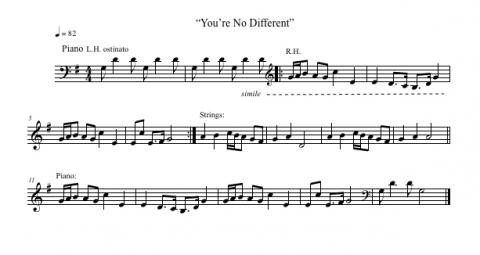

Although Silvestri’s initial theme didn’t provide melodic resources for other cues, the sound of the piano heard at the outset remains central to his score. “The piano itself became thematic,” he says. “We used it as a sort of connective tissue throughout the score.” Silvestri wrote different themes to flesh out the characters and their relationships. The second theme heard, “You’re No Different,” also features the piano (see page 27, example 1). While it differs from the opening theme, it also has a childlike quality and is played over an ostinato.

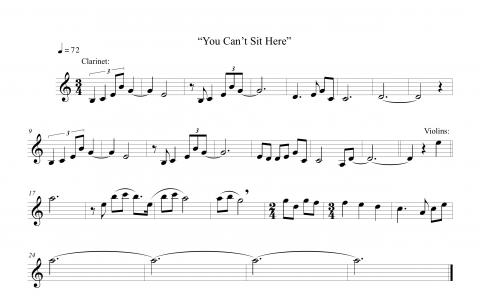

The cue titled “You Can’t Sit Here” (example 2) is an important theme that reappears in various instrumental settings. It’s the third theme heard in the movie when Forrest, as a child, boards the school bus for the first time. Most of the kids refuse him a seat next to them, but Jenny Curran (played by Robin Wright) says that he can sit next to her. She becomes Forrest’s first friend and, eventually, his love interest and wife.

Example 1

Silvestri chose the clarinet for the voice of the first half of this cue (bars 1 to 16) in its first few appearances in the film. Silvestri refers to it as “The Forrest Lonely Man Theme.” “The clarinet doesn’t generate the same number of harmonics as a flute or an oboe,” Silvestri says. “Acoustically, that’s a real thing. So to me, the sound of the clarinet is capable of suggesting loneliness. I used it to help communicate Forrest’s isolation and his inability to makes sense of what he sees happening around him. He didn’t understand so much of the world. Stating the theme with a solo instrument already has you on the path, but then the choice of the clarinet took that intimacy beyond to a sense of loneliness.”

Example 2 Bars 1-16 “The Forrest Lonely Man Theme” Bars 17-27 “Forrest and Jenny Theme”

Note the poignancy added by the wider interval leaps Silvestri employs in these themes as compared to the more scalar movement found in the previous themes. With the second half of that cue (example 2, beginning with the pickup to bar 17), Silvestri underscores the emotional spectrum of the relationship between Forrest and Jenny in scenes where their paths cross in future years. “I wanted to convey the feeling of someone looking back thinking of when life was the best it ever was,” Silvestri says. “When Forrest

and Jenny were kids sitting in the tree, life felt good and uncomplicated, this was before life’s problems came crashing down. That girl was going to become a drug addict and die of AIDS. Forrest would fall in love with her and ultimately see her—his best friend—die. The future was filled with pain for these two, but at this point, things were just rolling along, everything was fresh and wonderful. I was just following what I saw in the film.”

Example 3

The “Run Forrest Run” theme supports the action during several scenes when Forrest is running. It’s epic and gallant and played by the full orchestra. “The spotting of this scene was very interesting,” Silvestri says. “There were a number of earlier places where a composer could have dug into it. When the rock hits little Forrest in the head, there could have been music. But the whole scene is about the moment when Forrest discovers that he’s not crippled.”

Early in the movie, young Forrest is fitted with leg braces to help straighten his spine. As grade-school kids, Jenny and Forrest encounter bullying classmates who throw rocks and chase him as Jenny screams, “Run Forrest, run!”

“At this point we’re really doing movie music,” Silvestri says. “Bob had the camera on Forrest’s face as he runs and the braces break and fall from his legs. He over-cranked the camera to make it seem like time was slowing down. When Forrest looks down and sees that he is running like the wind without the braces, that’s when the theme finally kicks in. The music is about him celebrating that something he felt was an infirmity not only doesn’t exist, but he is actually a brilliant runner.” Silvestri’s theme is heroic and inspirational. A key change comes at the voiceover line spoken by Forrest: “From that day on, if I was going anywhere, I was running!” The theme reappears at key points in the film, always elevating the energy and drama of the onscreen action.

Telling the Story

Silvestri is well known among top movie directors as a composer who can write memorable themes and additional music that supports a storyline. “For a film composer, understanding the story and helping to tell it with music is very important,” he says. “There are a lot who write brilliantly but can’t write a movie cue because they don’t have a sense of story. Writing a movie theme is like songwriting. Helping a story with a theme is what I love and feel I understand. I see myself as a filmmaker who writes music.”