Technology and Music Consumption

By Peter Alhadeff '92 and Caz McChrystal '03

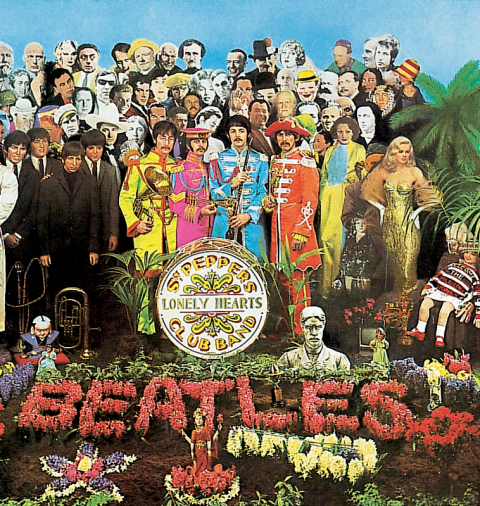

The 1967 release of the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album by the Beatles coincided with the popularity of stereo recordings among music consumers.

It is remarkable that the release of Pepper coincided with the explosion in popularity of stereo recordings. Pepper was optimized for effect in a way that the earlier Revolver could not be. Fifteen years later, when a then-young Music Television network (MTV) opened a slot for the first-ever appearance of a black artist, the medium of video (in tandem with the new CD audio format) similarly brokered Michael Jackson's Thriller as a smash hit worldwide.

Much creative genius was present in both records, but a new environment for listening and playing music helped. This factor was beyond the control of the Beatles or Michael Jackson. Quite apart from these artists not being involved in record-company operations, change was being fueled by such entities as the manufacturers of playback technology and the developers of cable TV and home video.

Technology Leads the Charge

By comparison, the history of music prior to the twentieth century centered almost exclusively on musicians and their instrument makers. Epoch-making events seemed inbred. Well-tempered tuning was perfected, and soon after J.S. Bach rewrote the musical book with his groundbreaking composition, The Well-tempered Clavier. The invention of the pianoforte fed into Beethoven's playing and writing and opened up a new sonorous sensibility. Autonomy and self-determination in music could be taken for granted, for music's fate seemed to depend, above all, on the collective body of musicians practicing and perfecting their craft.

From the left: Associate Professor of Music Business and Management Peter Alhadeff and alumnus Caz McChrystal '03

In many cases, this still applies today. But music is now a mass-traded commodity with management vested in many other ventures, notably the multimedia entertainment conglomerates. Increasingly too, nonmusicians have a stake in the making of music. Fund-amentally, by recording music, a performance can be sold separately from the artist. In addition to the record-company subsidiaries of the entertainment giants, consumer electronic manufacturers, PC manufacturers, and the telecommunications business all appear to hold the future of music in their hands.

As a consequence, the rise of talent, the vital input in the music supply chain, may no longer be the key to long-term vibrancy in the market. Over the past three decades, peaks and troughs in recorded music sales have been observed not to follow changes in artists' creativity and music making as much as the underlying shift in the technology of delivery and usage of music. Arguably, this is the new leading economic indicator of the music trade cycle.

Profits to Burn

For instance, when Netscape introduced its first Internet browser in 1995, it created a new market for traded goods-including music-on PC desktops. Free music file sharing would be born shortly thereafter. Also, the digitization of musical sound (the encoding of music into numbers that could be interpreted by hardware devices as a succession of on-off signals and reconstructed anew) had by then advanced to the point where cheap supplies of CD copiers could be widely marketed. The upshot was that the combined effects of Internet file sharing and copious CD burning-two events over which practicing musicians had hardly any influence-weighed heavily in the slump in music sales that began in 2000.

In fact, the primacy of technological change in the fortunes of the music industry had been most dramatically illustrated earlier with the CD audio revolution. A writer for the Economist described this as a case of "salvation through technology." In 1983, when record companies introduced CDs, vinyl records were dying, and cassettes were not making up the losses. For several years, sales per capita of full-length recordings had been in decline in most big markets, with North America and West Germany peaking in 1978 and Britain in 1975. CDs came just at the right time, eventually ushering in a golden decade in recorded music sales during the 1990s.

By the new millennium, practically every major trade organization for recorded music, including the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), portrayed business as largely driven by changes in end-user technologies. Technology, which in the 1980s had conceivably saved talent by averting a crisis, was now part of the problem.

Since recorded music is listened to through a playback device, the quality, affordability, and convenience of such a device has a critical impact on the volume of music sold. Consumer tastes have therefore become a function of the playback technology and not just the music. This was amply demonstrated during the 1980s when baby boomers rejuvenated the market in the 1980s by replacing their vinyl record collections (i.e., music they already owned) with the new CD recordings of their favorite albums.

If consumer preferences for recorded music are now embedded with the technology that delivers the sound, technology must be changing our connection with music. Take, for instance, Sony's Walkman, which opened up a new world of high fidelity and portability for recorded music. The revolution started with eight-track tapes in cars and continued with the adoption of cassette decks, but the Walkman freed music listening from the confines of the home and the car. At present, the portability of all recorded music is a key expectation of a new generation of music fans.

The Walkman in effect gave birth to a more personalized listening environment. This was because its release coincided with the aerobics craze and the quest for higher personal fitness goals that began in the United States in the mid-1970s. Before the Walkman, it had been customary to experience music in a sedentary fashion and in the company of others. After the Walkman, the idea of listening to music alone while walking or jogging took hold everywhere.

Boom boxes and portable CD players helped. But this is only part of the story. In the early 1990s after media and advertising became more pervasive, record companies started to seriously consider the potential of niche markets and individual consumer types. A new direct rather than blanket-target style of marketing emerged. Two music-tracking technologies finally enabled a real-time understanding of current demand. SoundScan (a bar code scanner located at retail outlets) and Broadcast Data Systems (a radio airplay monitor) brought an almost instant capacity for response by major labels to shifting consumer tastes at a local level.

The Internet, of course, has made the efficient micromanagement of recorded music sales a question of label survival. Napster's peer-to-peer software, developed by 1999, pointed the way forward to a new consumer base, and ever since, the business has grappled with the challenge of developing a suitable legal alternative.

At this point, in one form or another, technology is heading down the path of supplying music on demand. The immediate gratification of consumer wants is no doubt also pushed by the entertainment quality of most of the music sold around the world. Indeed, short forms such as pop sell better than classical or jazz in spite of the market being more sophisticated and diversified than ever beforeby music genres.

Three other events are notable for changing the general public's perception about music. In chronological order they are: video and the explosion of cable television, the advent of households with multimedia capabilities, and a new mode of interaction with music via the Internet.

No Static

First, in 1981 the business of music was jolted when a new cable network, MTV, went on the air. MTV showed short music videos that linked image and sound in an original way-a departure from the staid filming by network TV of bands in a static concert setting. Artists such as the Beatles and Elvis had explored the concept through their movies. When the music-video format struck marketing gold, it forever tightened the bond between artist and fan.

The intensity of the experience created a qualitatively different backdrop for music and dramatically changed the public's expectation about musical events. On the one hand, the medium typically demanded more attention than radio, because music listening could not be as incidental on TV and precluded other activities. On the other hand, the sensory awareness of an audio-video mix added information about the artist and gave fans a more intimate portrait.

The sound-and-image paradigm became entrenched in 1984 after Michael Jackson's previously mentioned success with Thriller, which sold 20 million copies. Since then, record companies have come to rely more on video as a promotional tool and less on the merits of stand-alone music. Unlike in the 1960s and 1970s, record business executives today consort with film, TV, and merchandise operatives as a matter of course.

Down from the Pedestal

Second, the recent integration of media on PCs is bound to have profound long-term effects. Any text, graphic, drawing, still or moving image, animation, and audio can be stored, transmitted, and processed digitally. This ease of access to different media in one location, the personal desktop, is changing our perception about music.

For one thing, music is more than ever a means to an end. It has become a player that struts and frets upon a stage occupied by other means of expression. Additionally, the consumer's ability to interact with objects such as the icons, alert boxes, and other software that are the basis of the Windows and Mac platforms generates the expectation of interactivity and control. CD-ROMs first exploited this. In short, the ubiquity of the PC is eroding the idea that music stands on a pedestal and is the venerable object that it once was.

Interaction

Third, music is now part of a revolutionary communications bundle. It coexists on the Internet with e-mail, instant messaging, and chat rooms. It moves, with the help of search engines and dedicated software among websites. For the user's purposes, it is as flexible as other media because it can just as easily be broken down into data bits and transferred at will.

The point of the exchange, moreover, might be only incidentally musical. Networks of like-minded fans are to some extent like empty vessels that require users to constantly and aggressively fill them with content. As a result, they develop into independent communities in their own right. Such is the case, for example, with the website of Pat Metheny (visit www.patmethenygroup.com), where affection for Metheny's music quickly becomes an exercise in collective communication, after which the music becomes the basis, but not necessarily the object, of daily interaction. Nothing in past history suggests how this might affect our listening habits.

In conclusion, it seems that music is not just music anymore. The pace of change in playback and communications technology has altered long-held popular perceptions and attitudes about music. It has superseded the discrete and one-dimensional model of audio-perception, exemplified today by old recorded media. The integrity of that experience, therefore, seems to have been undermined.

The tools for a new artistic fusion of aural, visual, and dramatic means of expression, as foreseen in Richard Wagner's concept of Gesamtkunstwerk (a term used in his essays describing an art form that combined various media within the framework of a drama), are already within the reach of almost every household. In addition, our changing relationship with music, from interactivity to connectivity, leads us to ask questions about our own culture and others. Finally, as music continues to evolve with the technology and with input from other yet unidentified players, it will likely be woven deeper into the fabric of our daily existence and become even more ubiquitous.