Financials and the Contemporary Artist

Nils Gums ’06

The advent of the Internet, coupled with the proliferation of low-cost, high-quality recording and other technologies during the 1990s, precipitated a much-discussed transformation of the workings of the music industry. Today, indie labels, major labels, and artists have gradually adjusted to the new landscape. And despite the dire forecasts about reduced profitability in the industry, many independent and major-label artists are creating and monetizing their music and brand at a profit.

After my graduation from Berklee in 2006, Matt Maltese ’04, Eric Zimmermann (USC ’06), and I entered the new music business by founding a company called RAWsession. We successfully produced viral videos showcasing new talent performing cover songs and originals in a one-take, live-studio environment as a new method of breaking talent.

Among the many artists we helped launch through YouTube videos is Karmin, comprising Amy Heidemann ’08 and Nick Noonan ’08. The duo was one of the first successful acts born on the Internet. Fueled by their success, our company (now called The Complex Group), handles the careers of a stable of artists, songwriters, and producers in addition to Karmin. After several hit singles and EPs, many domestic and international tours, and highly visible song placements, Karmin released Pulses, its much-anticipated full-length debut album on Epic in March followed by a U.S. headline tour selling out in major cities like Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

While the major labels continue to play a dominant role in the music industry, there is an increasingly larger role for entrepreneurial indie artists and their music business teams. Previously, revenues for artists signed to a major label came from a small number of sources. In today’s music-business climate, many artists have taken greater control over their revenue streams as well as operating expenses.

An artist’s musical style largely defines the demographics of the fans they attract and their marketplace, allowing the artist’s manager and business manager to form a clear business plan. These factors affect the venues and the scale of production of the artist’s live show, whether or not to work music to radio, brand partnership potentials, and much more. It’s impossible, therefore, to make a one-size-fits-all analysis of the revenues and expenses that would apply to every contemporary music artist. I hope this overview of how the financials work in the case of Karmin will be insightful for others in the popular music marketplace.

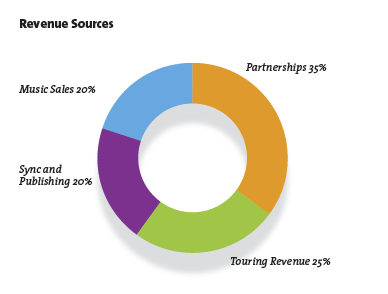

Revenue

Partnerships

The biggest revenue stream for Karmin is brand partnerships. Through the years we have partnered with Sony Electronics, Beats by Dre headphones, Coach, Hershey’s Twizzlers and Jolly Rancher candies, Dasani Drops (a subsidiary of Coca Cola), ROC-a-wear, GAP, ShoeDazzle, Vizio TVs and others. There are still future opportunities for Karmin with the makers of a variety of products in brand categories such as beverages and electronics to large apparel lines and fragrances.

Touring revenues

Since a majority of merch sales happen after shows, I have combined merch sales with touring revenue. It’s important to differentiate between hard- and soft-ticket sales. For hard-ticket dates, the artist receives a small guarantee from the venue paid by the promoter as well as a portion of the price of every ticket sold. That’s how the biggest-name artists filling the largest venues make millions of dollars.

For up-and-coming artists, it’s very important to tap into soft-ticket sales because they are not drawing huge crowds yet. They may not be able to sell out the Blue Hills Bank Pavilion in Boston on their own as easily as they could the Paradise Rock Club. If a college books an artist like Karmin, they usually offer a soft-ticket agreement. So even though the artist can draw an audience, since the concert is at a college, the venue already has a built-in crowd. In this situation, the artist may get a higher guarantee—let’s say $60,000 for a 60 to 75-minute performance from which the college might make $200,000. These dates are important opportunities for an artist to build a fan base and make money selling merchandise on tour. At the moment, merch sales are not a large factor for Karmin, but we are gearing up for a large marketing campaign for our e-commerce merchandise store.

Sync placements and publishing revenues

Sync and publishing income are the third largest source of income for Karmin. We get between four and six sync placements every month. Many are for TV and those fees tend to be smaller—maybe a few thousand dollars per placement. But some sync placements for a national ad campaign can pay well: up to $150,000 for the publishing side plus $150,000 for the use of the recorded master. For Karmin, those fees are applied toward “recoupables”: that is, the money advanced to the group by its record label (Epic Records) and publisher (SonyATV). It’s important to note that synchronization placements are not only a great source of revenue for a developing artist but also have a huge promotional value (e.g., a song being played in the new BMW car commercial during the SuperBowl).

Music sales

In the music sales category, I have combined the percentage of revenue derived from the sale of physical albums, digital downloads, streaming music payments, and YouTube royalties.

Label and publisher advances

Whenever an artist signs with a label or publisher, they get an advance that figures into that fiscal year’s income. These advances are recoupable, meaning they need to be paid back before the artist receives royalties from the label or publisher. We negotiated high advances for Karmin because the group was fortunate enough to be in a bidding-war between all major companies on the record and publishing side. Karmin has just about completely recouped the publishing and record advances they received thus far. These advances are paid out early on in an artist’s career and are there to support the artist’s living expenses and are calculated to last several years or until recoupment.

There will be future marketing expenses with each new album, and these are usually 50 percent recoupable, but as artists become established, recoupment happens faster. Many successful artists don’t recoup and make a profit until their third album. But as much as 96 percent of the artists on a major-label roster never recoup. The major-label business model is set-up such that less than 4 percent of the artists on their roster recoup and bring in enough money to carry the rest of the label’s artists. Venture capitalists in other businesses think the same way. Out of a portfolio of 100, perhaps two to five investments yield a return on investment, but they often pay back all combined investment—and then some.

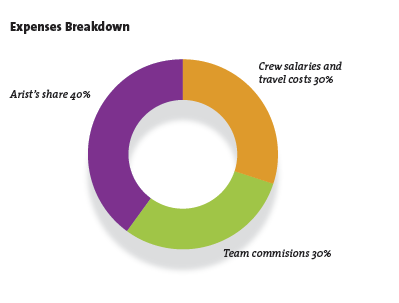

Expenses

Overhead is high for most touring artists on a major-label level including headline shows, support slots as well as TV and radio promotional appearances. Heidemann and Noonan tour with at least three musicians, a monitor engineer, front-of-house engineer, stage manager, tour manager, and a production or lighting person. (The venue generally provides the person who sells merchandise.) Karmin’s tour bus can sleep between eight and 10 people, so the whole crew travels together. If a given tour grosses half a million dollars, associated expenses may take 30 percent of that number, leaving Karmin with about 40 percent after these expenses and team commissions have been deducted.

Team commissions

Of the many items on the expenses side are team commissions. These are the fees paid to lawyers (5 percent), personal manager (15 percent), business manager (5 percent), and booking agency (10 percent). As artists become more established, they can negotiate these fees downward. Of course, there are also expenses for the actual travel costs and the payroll for musicians and crew members. We also hire publicists, wardrobe, hair, and makeup stylists who are not full-time members of the team. They come on for the promotion of an album or career milestone.

Promotion Costs

Radio tours

An artist’s label usually pays the expenses for a radio tour (a non-recoupable promotional expense). Initially, radio tours may just consist of the artist and a guitarist or other accompanist so that the entire operation is cost effective and easily transportable via SUV or Sprinter van. Artists may visit some 50 U.S. markets to do on-air interviews and promote their current single during any given single cycle. As the artist gains in popularity, this operation will naturally grow in scale and cost, but the number of shows and markets visited will decrease.

Radio festivals

When trying to get traction to work a record into the top of the charts, artists have to play the “radio game,” which often means playing big radio festivals at break-even cost. Most new artists will start out playing the preshow tent and then gradually graduate to playing during prime time on the main stage. In Boston, a station like KISS 108-FM will have a tent outside the venue where up-and-coming artists perform, while the more established artists play the main stage. Karmin recently played for a big radio festival on the main stage at Xfinity Center in Mansfield, MA. Ariana Grande, Jennifer Lopez, and Karmin were among the headlining acts. An artist may get paid around $15,000 for such a performance on the main stage, but again, these fees usually just cover production costs and in most cases don’t bring home much profit for the artist.

These festivals are, however, great opportunities to play in front of 10,000 to 20,000 people each night. Karmin has performed at many of them and shared the stage with Lady Gaga, Jay Z, Bruno Mars, and others.

Television

TV appearances also offer very important mass media exposure, and are nonrecoupable expenses underwritten by the record label. If an artist plays on Late Night with Seth Meyers or Good Morning America, the artist’s label absorbs the production costs for the musician’s salaries plus costs for rehearsal, equipment or backline rentals, lighting, per diems, travel, and hotel costs. An artist may also pay for choreography coaching if needed, depending on how elaborate the production will be. For a major TV performance by a priority act on a major label, costs average between $10,000 to $40,000 per TV appearance. For awards shows, it’s in the low six-figure range.

The Bottom Line

So what percentage of the gross revenue goes to Karmin? Typically, just less than 50 percent—and that’s a good number. We are quite frugal and manage expenses well. We invest money to hire top-notch people in key decision-making positions and they help us keep expenses as low as possible. For instance, the right tour manager and booking agent will effectively string tour stops together to keep travel and lodging costs reasonable. If you’re not careful about logistics, you can waste a lot of money. Well-managed expenses enable artists to keep more of the pie.

Ultimately, a manager oversees a huge operation, managing relations with the record label, publisher, brand agents, booking agents, tour manager, business manager, attorney, and people focusing on the digital side of things. My job is to ensure that there is a profit at the end of the day.

As an act grows, it invests more money to further its brand, sound, and stage performance, which helps elevate its profile. Ultimately it can draw larger crowds to live shows, merchandise, recorded music, brand partnerships, philanthropic causes, and much more. As an artist evolves and creates a deeper catalog of material, the hard-ticket model becomes more viable and ultimately much more profitable than soft-ticket dates. Despite what doomsayers say, there is still plenty of money to be made in the new-music economy.

Nils Gums is a graduate of Berklee’s music business/management major. He is an executive at The Complex Group, an artist development and management company with a record label and a TV and film production arm. He has helped to launch the careers of several fellow alumni and signed his flagship artist Karmin to Epic Records. Visit TheComplexGroup.com. Gums is also a Berklee trustee.