Robert Etoll '73

Expert Testimony: Given by movie trailer composer Robert Etoll ’73 to Mark Small

Rumbles, pulses, and orchestral sweeps

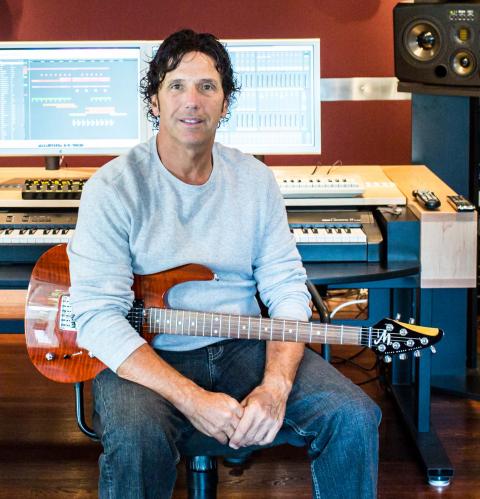

Robert Etoll

Originally from Troy, NY, Etoll burnished his guitar playing, composing and arranging skills at Berklee before heading to Los Angeles. While pure musical imagination is the focal point in many of his cues, it’s his work with sound design elements that has many in the business crediting him with altering the sound of contemporary trailers. His copyrighted swishes, pulses, rises, rumbles, and percussive noise montages add power to the onscreen action. Currently Etoll’s catalog has 33 volumes, and three more are in production (visit www.robertetoll.com).

How did your path lead to writing music for movie trailers?

After finishing at Berklee, I was playing with a band all around the East Coast. When the band broke up, I wanted to take things to another level. I didn’t want to go to New York City. So, in 1976, I moved to L.A. to look for work as a session or touring guitarist.

I got lucky when I started working with Alphonse Mouzon. He was looking for an educated rocker who could play over various rhythms and chord changes. His group was playing at European festivals. That was great for me because I got to meet a lot of my musical heroes from the jazz world.

I was also getting some session work, and I started to notice that the songwriters and producers were making more money than the players. I started to write some songs. I’d been playing tennis with Irving Azoff and got to show him one of my songs. He said it would be a good song for Richard Perry. I got together with Richard and played it for him. He liked it and was producing the Pointer Sisters at the time. They also liked it, and it ended up on their album.

In the late 1980s, I was signed as a staff writer to Warner/Chappell Music and, later, with MCA. The Pointer Sisters, Reba McEntire, and a lot of international artists were cutting my songs. At the same time, I was scoring lower-budget films, and one of the directors was also an editor for movie trailers. He liked my work and asked me to write a 30-second TV spot for The Godfather Part III. Everyone at the studio liked it and I started getting calls for more music. So I got into scoring movie trailers in the early 1990s. Back then it was all work for hire. Later I retained the rights to what I’d written.

When did you realize that your work for trailers could be licensed for other projects?

I didn’t start licensing my music until around 1998 or 1999. By then, I’d written special scores for more than 300 trailers and TV spots. When I was writing these scores, I realized that I should compile everything I owned. I began licensing the old material and writing new stuff for a catalog.

That’s when I realized that licensing was a whole different business. My smartest move was talking to the editors, music supervisors, and producers because they would tell me what they needed. They didn’t have enough sound design elements: hits, swishes, and other sounds. They wanted something to create impact in their trailers. I was willing to spend months creating these sounds and putting them on discs to get them out there. At first, people wanted to treat them like sound effects that they could just buy outright. I stood my ground and told them that they had to license them from me. After about a year and a half, the licensing for my sound design elements really kicked in. There were three components to them: sound design, percussion, and rises. Editors didn’t have enough trailer rises, and I caught that at just the right time.

Some have called you a trailblazer for sound design in contemporary trailer music.

Well, I didn’t invent trailer music like Henry Ford didn’t invent the car. But he was able to figure out a way get them out there. I made these sounds available in a package format. The whole key to this business is accommodating the editors, knowing what they need. I was able to deliver that. When I was finishing Sound Design Vol. 4, one or two editors told me they didn’t have enough “rumbles.” They wanted these short five- or six-second sound elements that would shake the theater. So I got together with another composer and we compiled about 25 different rumbles. Then, boom, we were getting licenses like crazy.

When you began this work, did you have a studio?

Yes, I started out with a studio in Culver City. The composers I work with all have their own project studios. In my studio we have enough space to record four or five strings or three French horns for sweetening. When we create what we call “premium releases” for our catalog that might involve 24 string players as well as horns, we’ll go to a bigger commercial studio. One of my composers went to Prague to record an 80-piece orchestra.

Do you have a stable of composers that help you create your tracks?

I have 15 composers that I can call at any time. I’ll hand pick them for certain projects. Whether I write the music or not, I produce everything. We have three projects going on right now. I have nine composers working on two of the projects that have the working titles “Dark Adventure” and “Emotional and Inspiring Release.” We are also working on Sound Design Volume VI.

Can you give an example of how you approach sound design?

I might bring drummers in and we sample all kinds of drums, and bang on brake drums and coils. Then I compress the samples, distort them, add ambiance, and more. There are sample libraries out there, but I try to get as much live sound as I can. I am planning to record a bunch of different drum rolls. For instance, I might combine a big bass drum and a taiko drum or a timpani and a taiko drum. Editors love drum rolls because they help with transitions.

What range of sounds and emotions do you offer in your library?

We have epic, action, comedy, and a series called “Outrageous Elements.” Those are perfect for horror films. We also have a release of pulses. It is important to market them individually rather than combine them so the editors know right where to go when they want pulses.

Given the number of people who now create music libraries, your timing for getting into the business was fortuitous.

True. It’s gotten very competitive. It’s a lot harder for people to get their library noticed.

Film composers are now looking for another angle and are trying the trailer world. So for anyone who is trying to get into this business, the material better be good and have something unique about it. Everyone knows how to do classic trailer music these days. It’s important to try to figure out what will be going on a year or two from now. We push the envelope and try to anticipate what will sound fresh to the editors.

What is on the horizon for Q-Factory Music?

I want to take things to the next level for the editors. The movie trailer has become an industry in itself—some trailers are actually better than the movies! I love it when I go to the theater and hear trailers with our music and impacts. I feel that I have the best job in town!