Some Rights Reserved

With the increased use of the Internet, the music industry has experienced across-the-board changes. The dawn of the digital age has given rise to myriad copyright challenges in the music world. At first, it was peer-to-peer sharing programs that allowed people to freely trade Christina Aguilera and Limp Bizkit tracks over plodding dial-up connections. Soon, the Recording Industry Association of America began to strike back with infringement suits against a select number of violators. Many cases were settled for a few thousand dollars. One unfortunate Boston University graduate student, Joel Tenenbaum, was hit with a six-figure fine for sharing 31 files from Kazaa.

Every few years, it seems that a new chapter is written in the ongoing story of copyright law in the music world. With the establishment of the nonprofit Creative Commons organization, which strives to expand the range of works available for the public to share and build on, the copyright field has seen further evolution. At its core, Creative Commons licensing aims to provide a "some rights reserved" approach to traditional copyright, affording copyright protection to artists while allowing certain uses of their work. Such licenses are available for a number of art forms, from photography to video and, of course, music.

It's a novel development in the area of intellectual property law. "The benefits of Creative Commons are that it gives control back to the copyright owner to loosen copyright restrictions and make it more adjustable," says Jessica Silbey, a professor at Suffolk University Law School in Boston and a specialist in intellectual property. "A copyright owner could allow for copying but require attribution," Silbey continues. "Attaching a Creative Commons license to your copyrighted work also serves to provide notice to the world of your intentions for your work."

From (c) to CC

Unlike other areas of intellectual property law-such as patents, which can be acquired after a lengthy and sometimes complicated process-attaining copyright protection is actually rather simple. The laws for copyright in America state that one is protected if they create, according to the United States Code, "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression." For musicians, that can mean recording a song or simply writing out a score. Once the creation is transfixed, it receives protection.

Copyright protection for works created after January 1, 1978, lasts for the author's life, plus an additional 70 years. Every musician or producer with material under copyright is afforded certain rights. The owner of the copyright can reproduce the work, distribute it, and perform it publicly. If another party infringes on these exclusive rights, the copyright owner can bring a suit for a number of remedies that range from injunction to monetary relief and, in some cases, criminal charges.

With this long-standing system in place, one might wonder exactly how Creative Commons fits into the picture. Creative Commons was founded in 2001, and by the end of 2002, the organization released its first set of licenses. Within a year, nearly 1 million CC licenses were in use. By the end of the decade, that number was approximately 350 million.

| With the establishment of the nonprofit Creative Commons organization, which strives to expand the range of works available for the public to share and build on, the copyright field has seen further evolution. |

Creative Commons maintains the protection afforded by traditional copyright. But CC licenses, which are free, afford different privileges by permitting others to copy or reuse a work commercially or noncommercially. Since CC licenses are an attachment to typical copyright, the licenses last as long as the copyright of the work.

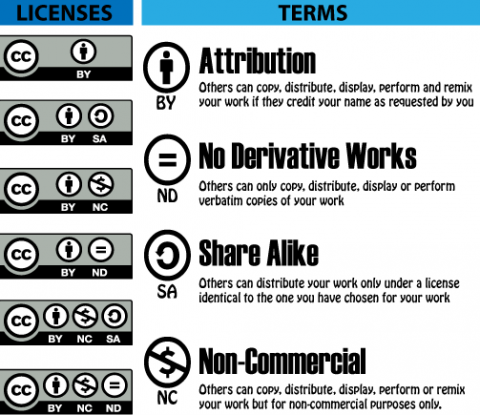

The fact that musicians have six different types of CC licensing to choose from-each with an escalating level of restriction-complicates things a bit. [See "Six Types of CC Licenses" on page 36.] The simplest level, known as CC BY, allows others to use a work as long as they attribute the original creator, even when the use is for commercial purposes. On the other end of the spectrum, the CC BY-NC-ND license allows noncommercial downloads and sharing with attribution but prohibits derivations.

Most CC licenses are used for nonmusical purposes. The photo-sharing website Flickr has roughly 100 million CC licensed photos. Middle Eastern news giant Al Jazeera uses CC licenses for its videos. However, CC licensing has begun to play an increasingly prominent role in the music world. Established national acts, such as Nine Inch Nails, have even begun releasing albums using this form of alternative protection. And it appears that the role of CC licenses will continue to grow.

Attracting an Audience

A software developer by trade, Josh Woodward always had a keen interest in different forms of public licensing in the computer world. It just so happens that Woodward is also a singer/songwriter. For him, the concept of Creative Commons seemed like a perfect fit, especially because the Ohio-based musician/software developer wanted to get his music out to the public.

"I started out just giving my music away for free because I thought nobody would really be all that interested," Woodward says. "When it started getting attention, I realized I was on to something, so I kept it free. For me, Creative Commons was a way of imposing order on the chaos of just dumping songs out there. It gives me some amount of protection against abuses while clearly defining to my listeners what they're allowed to do."

Woodward has released all his music under CC BY protection. The license allows people to do whatever they like with his 170 songs, as long as they attribute the music to him. In fact, all his songs are freely available on his website for download (though they are also available through paid channels, such as iTunes and on physical CDs).

On the surface, it may seem like an ill-fated business model. But according to Woodward, using CC licensing has been an indispensable tool in getting his music heard. "Creative Commons licensing has one enormous advantage: exposure," Woodward says. "A small but significant percentage of your audience will want to give you money to support your music. And the more people who listen, the more people will pay you for it." The exposure has paid off for Woodward, who says that he has received paid placements for his music in films and advertisements.

"These days, a musician just getting started with no established audience really has almost no chance to break through the noise by following the old formulas," he says. "Releasing your music for free under Creative Commons breaks down barriers and opens your music up to the world. Even for more established artists, only the fans that want to pay for your music will pay you, the rest will download your music for free anyway. Why not take advantage of that by building goodwill?"

Unlike Woodward, Kristin Hersh had spent more than two decades immersed in the world of traditional copyright until a few years ago. While in high school in 1983, Hersh formed Throwing Muses, the alt-rock outfit that ultimately signed with the English rock label 4AD. Since then, Hersh has embarked on a remarkably productive music career. Just last year, she released her ninth solo album. For Hersh, deciding to release music under CC licensing greatly simplifies things for her as an artist.

"I like the fact that CC cuts out the middleman for those interested in using or sharing my work in ways that are agreeable to me," Hersh says. "It eliminates the need for intermediaries by allowing me to state clearly and in plain English the kinds of usage that I'm OK with. I also like the fact that if someone comes across a CC-licensed work and wants to use it commercially, it provides an easy way to contact me as the author so that I can grant any other permissions or issue appropriate licenses."

Hersh first heard about CC licensing when she released Free Music, an EP by her band 50 FOOTWAVE. The band wanted to post its music through a forum where CC licensing was a requirement. Before then, Hersh had never heard of this alternative to copyright protection. But for Hersh, experimenting in this novel area of copyright was something she needed to do.

"I wanted to see what would happen when I allowed sharing of my music on my terms on music blogs and in podcasts," says Hersh, who released her 2008 album Speedbath and other projects under CC licensing. "I also wanted to facilitate a more immersive experience with my music for people interested in taking it apart and using the elements as building blocks for their own works. I used CC licenses for 'stems' for the purposes of remixes. It's been amazing and we've received hundreds of remixes based on my a cappella tracks and stems."

An Acceptable Use Policy

Today, it's not just musicians who dabble with CC licenses. John Buckman of Berkeley, California, founded Magnatune, a record label that uses Creative Commons licensing, in 1983. Many of the nearly 300 artists on Buckman's roster are world and classical musicians, and their music is released under CC BY-NC-SA protection, allowing for noncommercial uses that are credited to the artist and licensed under identical terms.

By using a CC license that provides a strong level of protection for his artists, Buckman sees his business model as a way to restrict public uses that may be detrimental to his clients while simultaneously encouraging others to use and propagate their music.

"[The license we use] is a significant limitation, which companies and other product makers, such as websites and games, are not willing to abide by, and so they seek us out, as holder of the copyright, for a traditional music license agreement," Buckman says. "The CC license gets our music heard, and then copyright is used to make money when the customer also wants to make money using our music."

Becoming involved in the forefront of the digital sharing movement is nothing new for Buckman, who is the chair of the board of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit organization that actively fights for digital rights. According to Buckman, creating a business model that centers on expanding and protecting the public's ability to use music is a must.

When asked about the potential downside of CC licensing, Silbey says that on the legal side of things, the issues are nonexistent. "I cannot think of many downfalls to Creative Commons," she says. "But some people have suggested that Creative Commons licenses, [by] relying on copyright restrictions as their foundation, reinforce the notion of copyright as a necessary property right. And yet Creative Commons is, in a sense, trying to provide an alternative to copyright as it currently exists in the Copyright Act. Some people point out the inconsistency of the two positions."

Likewise, from the musician's perspective, shifting from traditional copyright to CC licensing has not yielded negative results. Regarding the potential downside of artists using CC licensing, Hersh says, "I suppose that theoretically, it can be seen as subverting the performance royalty, but in practical terms, I haven't experienced this to a significant degree."

Ultimately, Hersh recognizes CC as a tool and suggests that other musicians consider alternative licensing. "I recommend CC licensing as a tool in the promotion of music," Hersh says. "But I also recommend that other musicians think it through, do their research, and come to their own conclusions. It's been a powerful tool for me, for sure."

Andrew Clark is a third-year law student and writer based in Boston.