Healthy Competitions

Jack Perricone

Dave Petrelli '05

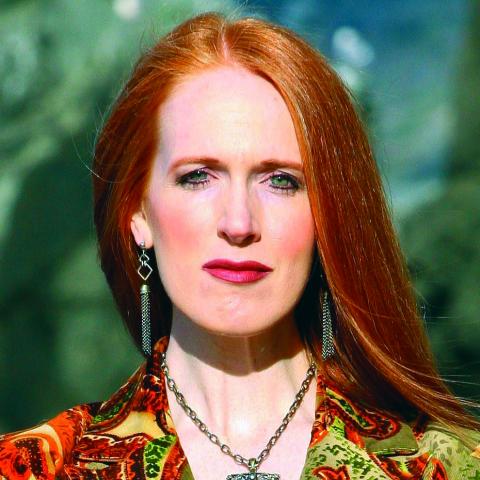

Katie Miner '99

Jon Aldrich

Matthew Cusson '99

Lior Shamir '99

What makes a song great? Most would agree it’s a magical union of poetry and melody that invokes some degree of emotional resonance. Some truly memorable songs come from songwriters that maintain a cult following with their distinctive, idiosyncratic viewpoint. But historically, the most renowned songs tap into mass consciousness. By communicating something with universal appeal, they transcend many of the barriers that isolate us in our daily lives. In this light, a great song inspires unity and a mutual understanding.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, pop music hadn’t yet fallen prey to analytical restraints such as “artistic integrity.” As a result, songwriting got mighty competitive as folks realized that there was money to be made. At New York’s legendary Brill Building, pop tunes were cobbled together with an amusing factory-like mentality. Carole King and then–husband and writing partner Gerry Goffin would sit locked inside a tiny room, perched at the piano, figuring out ways to breathe new life into the chord progressions and stories that fueled their last few hits—not to mention those of their competitors. King’s been known to joke good-naturedly about how ideas were openly swiped and recycled with the hopes of continuing to cash in as she and Goffin strained to hear other writers composing in the surrounding rooms. At the time, it all had a playful trial-and-error feel: win some, lose some, no big deal. Yes, they were hungry for success, but not the way aspiring songwriters are hungry these days.

It used to be that a career in the arts was a serendipitous, unusual happening, not something young adults pursued en masse. You didn’t choose art; rather, it chose you. But fast-forward 50 years: now creative careers are highly sought-after, and the music world has become an extremely complicated industry. We take our pop music much more seriously now, and writers encounter mind-boggling competition, to the point where even just getting noticed seems like an impossible dream. The music market in particular is so crowded that even the most driven talent is forced to make tough choices about how to become a bigger fish in an exponentially widening pond. And this is precisely why increasingly more songwriters have chosen to roll the dice by participating in competitions with the hopes of attracting attention to their work.

Contests that honor achievement in songwriting are nothing new, but throughout the past decade their popularity and scope have increased substantially. Rest assured, whether delineated by geographic region, musical genre, or even subject matter, a contest exists for whatever type of songs you write. And with cash prizes often in the five-digit range plus complimentary gear and other perks, the winnings are nothing to scoff at. Even still, desperate times haven’t robbed songwriters of their dignity, and most approach the contest model with a healthy skepticism. And one thing songwriters need to understand is that competitions do not provide shortcuts.

A Shortcut?

“Aspiring songwriters get in trouble when they start looking for the quickest way to achieve their musical goals in the shortest amount of time by doing the least amount of work,” says singer/songwriter Dave Petrelli ’05, the director of events for the Nashville Songwriters Association International (NSAI). “Less-than-legitimate song contests can take advantage of that by promising really unrealistic things.”

Songwriting Department Chair Jack Perricone paints an even darker picture. “Since most people don’t have a clue as to how difficult it is to write a well-crafted song—one that communicates deeply to a lot of people—they look at their song as a treasure that is just waiting to be discovered. But it might be meaningless to anyone else,” Perricone says. “The folks who run these contests see instead a group of naive people whose heads are full of fantasies and who are willing to send them $25 to $40 per song just to have someone—who may or may not know anything about judging a song—listen to their ‘treasure.’ These two perspectives form the playing field on which songwriting contests occur. Enter at your own risk!”

There’s enough genuinely positive energy around songwriting competitions to temper Perricone’s cautionary tone, however, so the real issue seems to revolve around discerning which ones are on the level. And when it comes to evaluating a contest’s true value, earnest writers emphasize purity of purpose and right-mindedness over cash and prizes.

“Every songwriting contest has its own criteria and reason it exists in the first place,” Petrelli elaborates. “Some accentuate the search for the next ‘hit’ song which, as we all know, doesn’t necessarily equate with ‘well crafted.’ Many are open to both professional and amateur writers. Some offer cash prizes; others highlight performance opportunities. I know that, for our part, the NSAI Song Contest really does focus on the craft of the song itself and structures prizes around opportunities for aspiring writers.”

Contemporary Christian songwriter Katie Miner ’99 adds that “the key is selecting the right competitions for one’s goals and that have credibility with the industry. As well, those competitions need to work for you when and if you do well in them. A competition may open some doors, but there’s much work to be done to get through and inside.” Miner should know, she’s been a finalist more than a dozen times in a handful of different contests, including American Idol Underground, Billboard World Songwriting Contest, and Unisong International Songwriting Contest.

Image versus Skill

Given our culture’s current fixation with flashy reality shows like American Idol, artists need to be wary of involving themselves in anything that blurs the line between image and skill. Televised competitions reinforce our unfortunate but all-too-human tendency to let appearances unlock the doors of opportunity. Refreshingly, it seems that the best songwriting contests retain a wholesome facelessness. “Maybe because the practice of songwriting is such a private thing, and most people have no idea or care who actually wrote the song they’re hearing,” says Berklee Associate Professor of Songwriting Jon Aldrich. “It’s just a less image-driven or popularity-based aspect of the industry.”

“The focus in a songwriting competition remains on the song,” says International Song Competition (ISC) founder and Director Candace Avery ’81. “There’s no consideration for image, age, sex, or stage presence.” Former Berklee voice student Kyler England ‘’00 concurs, “Only the song matters in these competitions. None of them look at photos or your website. A pretty face just isn’t part of the judging process.” England also has extensive experience having landed first place in both the Mid-Atlantic Songwriting Contest (2003, 2004) and the Unisong International Contest (2004), among others.

Matthew Cusson ’99, the 2009 winner of the John Lennon Songwriting Contest in the Best Jazz Song category, agrees. “The Lennon Award is great, because the judges choose the winner solely based on the melody, chords, and lyrics,” Cusson notes. “When I submitted my songs, there were no pictures of me or any of the other songwriters. That really maintains a diligent focus.” Cusson, who openly admits that the concept of competition in music usually makes him bristle, was also a Lennon Songwriting finalist in 2008 and, most recently, won the Maxell Song of the Year with his song “One of Those Nights.”

Advertising sponsors are another potential deal breaker. You won’t find serious songwriters tripping over themselves to enter competitions subsidized by companies unrelated to music. Lior Shamir ’00, the managing director of the renowned We Are Listening contest, puts it succinctly. “Bacardi, Vans, Jack Daniels, Rizla have all held song contests. Who wins? Who cares? In contrast, a music company that runs a song contest is or should be recognizing the very ‘best,’ for lack of a better word. Their business depends on it, as does the reputation of their panelists.”

And Miner adds, “The right sponsors make a big difference, as they convey credibility, which translates into increased participation, renown, and revenue for the competition,” noting that quality-name judges put the icing on the cake.

An Earthy Craft

It’s comforting to note that, while technology broke the levees that used to make careers in music less accessible, songwriting remains a comparatively earthy craft. True, writers may not put pen to paper the way they used to. That’s especially true in the urban market, where the lines between writing and production are often hard to discern. But when a song is distilled down to its essence, no amount of digital buff and polish can force it to better convey feeling. It either moves people or it doesn’t. The ingredients haven’t changed.

“The way I look at it, a good song is intended to do one thing: evoke emotion,” Petrelli says. “Make me laugh, make me cry, make me angry, make me sad, make me smile, but make me do something besides turn the radio dial. Whether you do that through a really fantastic lyric or an amazing melody doesn’t matter.”

“I think the songwriting process has not evolved as much as one would imagine,” Shamir opines. “In some genres, creative technology tools play a major role in the copyright. But in my mind, stripped of all the bells and whistles, a great song is a great song, even if it’s more of a ‘track’ than a standard verse-chorus.”

“It’s difficult to ‘put one over on knowledgeable songwriting judges,” Aldrich adds. “They can usually hear beyond the performance of the song and assess the craft of construction itself.” Avery agrees, “I believe 100 percent that the songwriting transcends every creative or not-so-creative aspect of the song. You can’t Pro Tools the songwriting.”

Avery went on to surmise that the best songwriting competitions indeed combine all these factors: quality judges, respectable sponsorship and useful, appropriate prizes, plus less obvious attributes such as follow-up and accessibility. “When our yearly competition ends, ISC continues to nurture its winners, from helping to pack a club with A&R people—as we did last month for Kate Miller-Heidke, last year’s grand prize winner—to offering complimentary showcase slots at various conferences, touring opportunities, and much more,” Avery says. “ISC also maintains a high level of transparency. We say who our judges are, what our prizes are, and what our judging criteria are to foster a degree of trust. This is invaluable.” As for murmurings that competition entry fees are dictated by greed, Avery disagrees. “I think that’s a ridiculous suggestion,” she counters. “A competition that doesn’t charge an entry fee will be very limited in its resources, which ultimately impacts negatively on the entrants and winners.”

Fair enough, but Perricone suggests starting out modestly. “Contests that limit the entries to the amateur or nonprofessional class are better contests than those open to everyone [pros and amateurs alike],” he says. “Other than that, the best contests I know are those sponsored by BMI [which houses the John Lennon Scholarship Contest] and Peer-Southern. Both limit the entrants to a collegiate age group and charge no entrance fee.”

Great Expectations?

In the end, the outcome of a writer’s experience entering a contest—large or small—is going to depend greatly on the writer’s expectations going in. Similar to relying on diet without exercise to lose weight, placing near the top in a well-reputed competition will not single-handedly propel a career into the stratosphere—unless, of course, you’re one of the lucky few.

“We have a proven track record in past years of winners going on to get signed to music publishing contracts, record contracts, and hit the charts,” says Eddie Phoon, the event director for the USA Songwriting Competition. “Kate Voegele got her start by winning first prize at the 2005 USA Songwriting Competition in the Pop category; the record labels took notice. We even placed her at our showcase at South by Southwest, where she was signed after the show by Interscope.” Voegele’s winning song pierced the Billboard top 40, and it was no fluke: her sophomore release scored a slot near the top of the 200 Albums chart, and she’s gotten some serious radio airplay. Another USA Competition success story is that of Ari Gold, who attributes the high-charting success of his single “Where the Music Takes You” to the buzz generated by his win six months prior.

After some prodding from Perricone, Emily Shackelton ’07 entered the John Lennon/BMI Foundation scholarship competition and won, despite doubt that her song would even get listened to. “I was definitely proven wrong,” Shackelton says. And the win has really made a difference. When Shackelton moved to Nashville, BMI set her up with a rep that landed her a publishing deal. Additionally, last year she placed as a runner-up in the American Idol songwriting contest, and subsequently crowned idol David Cooke sang her song on TV, resulting in nearly 200,000 iTunes downloads and a number 15 spot on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

Shamir speaks in less specific terms but still makes a great case for his contest. “Speaking for We Are Listening only, I’m proud to say that we have contributed to the careers of our winners by getting them great licensing deals, management, prominent college radio rotation, and good press,” he says. “In more ways than one, we have financed and introduced the very opportunities that most of our winners lacked the resources for or had access to.”

Yet despite these success stories, Petrelli warns against keeping one’s eye on this kind of prize; competitions offer potential opportunities, not easy solutions. “A lot of people are desperately searching for that one piece of notoriety or acclaim that, in their minds, will catapult them to a place in the music business they think they want to be,” he says. “Song contests can be really great and can open many doors for people. But it is neither practical nor realistic to completely rely on a contest as the potential doorway to success. There is no science to songwriting contests. Good songs get passed on all the time because music is such a subjective medium no matter how objective a particular contest’s rules and judges might be.”

Perhaps the most valuable prize is a much-needed boost in confidence, something that creative people can have a tough time balancing with a sense of humility in this frighteningly competitive marketplace. “I’m sure that winning a songwriting contest is a positive event, even if it’s only to boost the prestige or stroke the ego of the winner,” Perricone says. “Because more than money, songwriters need to have their songs acknowledged and to be given hope that they are not writing in a vacuum.”

Christopher John Treacy is a Boston-based freelance writer and operates Whizzboom Publicity. Contact him at whizzboom@comcast.net.