Entrepreneurial Spirit

From the left: RAWSession founders Nils Gums '06 and Matt Maltese '04

Mark Small

Brian Brodeur '91

Andrew Lepley

Brian Preston '93

Dana Sheridan '93

Thalia Sheridan

Video Pandemic

Just a year ago, Nils Gums ’06 and Matt Maltese ’04 launched their company RAWSession Inc. Their objective was to produce viral videos for new and established artists to enable their clients to tap into the inchoate but powerful link economy. Their RAWSession videos offer musical content that has credibility with fans and has boosted artists’ careers. Their work has gotten the attention of Rykodisc, Island Def Jam, and Pulse Recordings who have hired Gums and Maltese to produce viral videos for the RAWSession YouTube channel to help create and keep a buzz going for their artists.

The concept of RAWSession is to showcase artists in a live studio performance setting with bare-bones instrumentation and no studio tricks such as Auto-Tune. The final product offers the viewer a quality portrayal of the artist’s true capabilities. And viewer reaction has been overwhelming. To date, collective views of RAWSession videos tally more than 7 million.

Gums and Maltese started out producing cover versions of hit songs done by unknowns. As he worked in the logistics department at Universal Music Group, Gums pored over thousands of YouTube videos searching for content owned by Universal. He noted that the label claimed and then placed ads on illegally uploaded music videos and sound recordings when Universal owns 100 percent of the content, but didn’t claim indie covers of hit songs. “I discovered videos of unknown artists covering a top-charting song and getting millions of views by people searching for the original,” Gums says. “That sparked the idea to produce videos of talented unknown artists covering hit songs and helping the videos go viral to give the artist exposure.” It also revives interest in the radio version of the song.

“People aren’t going to search on YouTube for an unknown,” Maltese says. “We will record a cover and an original song with an artist. Then with some search engine optimization, the right keywords, and a description of the video, people will discover the cover song. If they like it, they’ll listen to that artist’s originals too.”

RAWSession videos have given a lift to the careers of 15-year-old vocal phenom Nikki Yanofsky as well as songwriters like Jesse Harris and established artists such as Sugar Ray, Jeremih, and others. “Natasha Bedingfield’s management found out about a band called the Katinas that we recorded doing Natasha’s song ‘Pocketful of Sunshine,’” says Gums. “Natasha watched the video and loved it. Her management reached out to us to inquire about the Katinas and possibly doing some work with them in the future. Opportunities arise that you wouldn’t think of.”

The medium also gives fans a better window into these artists’ talent. The idea of a simple musical setting makes the sessions easier to record, but more important, it lets a gifted artist really shine. “I love heavily produced pop music,” Maltese says, “but I love purely acoustic music too. I think the fans have a right to know what an artist really sounds like in a sparser setting.”

The production values of both the audio and video in RAWSession clips are far above the often fuzzy and distorted YouTube videos that were shot using a laptop or a Handycam. Gums and Maltese shoot their videos in high-definition in a professional recording studio, so the sound is also top notch.

For Gums and Maltese, the mission is to foster authentic talent by harnessing the power of the Internet, social networks, and Twitter. They believe that if an artist is great, word will spread and careers will develop. All indicators show that their instincts are correct. As for the future, they aren’t looking to go corporate. “I want it to stay viral,” Gums says. “We’re not opposed to expanding, in fact we are thinking of going into other countries to work with local artists there. But we want to remain part of what is being talked about and tweeted. We want to invest in the careers of emerging artists, but we aren’t looking to become a traditional record label. We’re interested in developing artists and having our relationship with the artists continue after the session ends.”

“People get what we are doing and appreciate it,” Maltese says. “There is a real need in the business for this kind of content.”

Negotiating Peaks and Valleys

As the founder of NewYorkDVD, Brian Brodeur ’91 has developed projects featuring artists such as Frank Zappa, Phish, Rod Stewart, Mike Keneally, Victor Wooten, Steve Gadd, Vinnie Colaiuta and many more. Brodeur and his NewYorkDVD team have been recognized with several awards including the DVD Association’s Excellence in Music DVD Award in 2006 for their work on Neil Peart’s Anatomy of a Drum Solo.

Shortly after graduating from Berklee’s Music Synthesis program, Brodeur accepted an engineering position at a Boston-area studio. The operation was struggling, so in addition to engineering, Brodeur worked long hours to build up the business by landing new clients and integrating new recording technology. Over the next two years, the studio expanded its revenue and capacity, and Brodeur discovered that he had an aptitude for business as well as for recording.

A subsequent job as an audio engineer and producer for a gaming company resulted in a chance meeting with recording industry pioneer Harry Hirsch, who dropped by while Brodeur was mastering an album. Hirsch later invited Brodeur to join his duplication and production team in Times Square. Brodeur accepted and packed his bags for New York.

“Working with Harry Hirsch was an incredibly educational experience,” Brodeur says. “He taught me about how much opportunity is out there. When I got to New York, [Hirsch] took me to the window overlooking Times Square and said, ‘Look out there, Brian. If you can get all the business within a square block of where we’re standing, we’ll be millionaires.’”

Over the next two years, Brodeur helped double the studio’s mastering and duplication business. He began feeling the urge to focus his efforts on a venture in which he would have a financial stake. The terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, prompted him (as it did many) to reexamine his priorities. “That got me thinking about my own choices,” Brodeur says. He again pondered the idea of starting his own business. “I asked myself, ‘If not now, when?’”

Brodeur began in earnest. The DVD format was just becoming popular, and Brodeur combined his experience at Hirsch’s company with his programming abilities to offer mastering and interactive design services for the new format.

Few producers in New York offered the combination of interactive programming and musical skills Brodeur possesses, and demand for his services grew. After landing two major clients, both publishers of music instructional videos, Brodeur incorporated NewYorkDVD before year’s end, and business began to take off.

By 2004, business at New YorkDVD was cranking. A major New York studio seeking to bolster its DVD capabilities offered to buy Brodeur’s operation. With the buyout pending, Brodeur moved his team into the parent company’s space before the deal was signed. Brodeur also sold the company all his gear. But what seemed to be a friendly merger soon more closely resembled a hostile takeover when Brodeur learned that the parent company had secretly hired away all his staff and that he was out of a job.

With a pregnant wife and his business suddenly pulled out from under him, Brodeur found himself once again starting anew. He had no office space, no equipment, no employees, and no clients. Exercising his entrepreneurial spirit, he bought some gear and built a small production studio in his home. Out of nowhere, a major client landed in his lap. Others soon followed, and once again Brodeur was back in the game.

When the recession hit in 2008, one of his direct competitors went bankrupt and handed some big clients off to Brodeur. “Instead of shrinking, we’ve actually been growing through the recession,” he says. Asked how he’s thrived in an environment where so many others have struggled, Broduer says, “I’ve been pretty conservative with my business. I haven’t tried to be all things to all people, and I’ve kept operating debt to a minimum. We’ve excelled in producing successful titles within niche markets by providing expert-level services in an industry that has become more and more commoditized.”

Reflecting on the peaks and valleys of his career, Brodeur says “Serendipity is a big part of it, businessgoes up and down. There are difficulties and windfalls that come around every corner, and you can’t always see them until they’re here. You have to learn to breathe with the changes. Don’t panic; you’ll get through it.”

Rolling with the Changes

In the mid-1990s when music technology became widely accessible and affordable, Brian Preston ’93 seized the opportunity to start his production company the Music Factory. It was a year after his graduation from Berklee, and “1994 was the beginning of the one-man show,” Preston recalls. “You didn’t need a separate engineer, a separate producer. Nowadays, that’s not so unusual. But then, it was an edge for me.”

Ever since, Preston’s multimedia production facility in Atlanta, Georgia, has been providing original music, jingles, and creative soundtrack design services for scores of clients ranging from AT&T to the Yellow Pages to the Georgia Lottery. Working as composer, arranger, engineer, and salesman, Preston—with help from his business partner Marc Battaglia, ’90—has logged more than 1,100 gigs.

Preston has learned that in today’s advertising industry, business acumen, adaptability, a thick skin, and the ability to communicate with and relate to all kinds of people are necessary attributes. Oh, and always remember: it’s about the client.

“My sole interest is keeping the client happy,” he says. “Brian Preston has no identity. I have to be quite a chameleon. If they want opera, it better sound like opera. If they want disco, it better sound like a Bee Gees record.” The challenge to keep coming up with “ear worms”—catchy tunes that you can’t get out of your head—keeps the business creative and exciting for Preston.

Over the years, he’s been able to roll with changes that technological advances have brought to the production and interpersonal sides of his business. Formerly Preston made pitches to ad agencies in person. The option to transfer demos via the Internet has afforded him access to clients in major and minor markets everywhere. The downside is that his competitors are everywhere, too.

It’s also more challenging to build relationships with clients on the Internet. Preston makes it a priority to build and maintain relationships through networking sites such as Facebook. Even the recent birth of his son Maxwell offers him an advantage. Being a new father “makes me a human in their eyes,” he says. “They will remember that.”

While technological advances have been a huge boon to his business, they also foster information overload and short attention spans that plague all in the creative industries. “It’s hard to get somebody’s attention,” he says. The typical client is now overwhelmed and distracted and ends up listening to a demo on an iPhone, for a total of say, five seconds. “It’s horribly depressing, actually,” he says.

While the Internet age has somewhat diminished the significance of proximity to the customer, Preston believes geography and the right facility are important factors in entrepreneurial success. He chose to launch his business in Atlanta because of its affordability and its openness, especially in comparison to Nashville, with its more established old-boy network. He also ruled out New York and Los Angeles because the competition there “would have chewed me up and spit me out.”

He started out in a loft studio facility in an old factory building in Atlanta rehabbed to his specs. But five years ago, facing increasing overhead, he decided to set up shop in the one-car garage attached to his house. Working from home helps the creative process, he contends. “I’m very comfortable here. I don’t have to commute, and I can work as many hours as I want.” He fully appreciates that the situation wouldn’t be an option without the Internet.

Preston estimates that 60 percent to 70 percent of clients have been adversely affected by the severe recession. “I have to be able to weather the storms,” he says. Another serious economic challenge for his profession has involved convincing the younger generation accustomed to “free” music that music has value and is worth paying for.

He maintains that his success would also not be possible without Marc Battaglia, his “silent” partner, in that Battaglia doesn’t interact with clients. Their partnership works well because they are “polar opposites,” Preston says. Preston first connected with his partner when Battaglia called Preston asking for advice about the industry. Preston is grateful to those who helped him when he started out, and invites alumni to contact him through his website at www.themusicfactory.com or via e-mail at brian@themusicfactory.com.

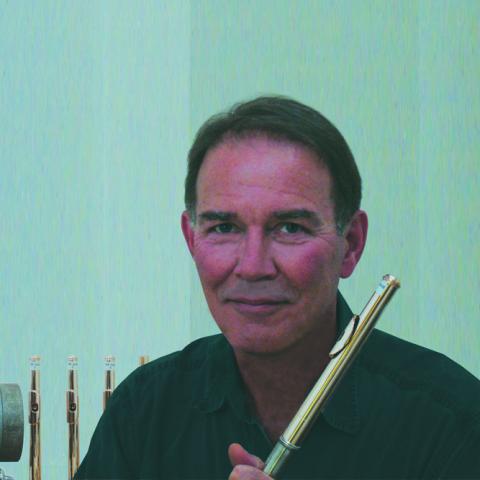

Old-World Mastery

Surrounded by lathes, an arbor press, and milling machines in his shop in Brookline, Massachusetts, Dana Sheridan talks about becoming a flutemaker after leaving Berklee in 1972. He gravitated toward his career gradually, and now, two decades after founding Sheridan Flute Company, he’s a respected maker in the flute world with numerous international classical and jazz musicians playing his instruments. Sheridan originally came to Berklee to study composition. Flute was his principal instrument, but he soon added saxophone to the mix. “I did it so I could get more work,” he says. “Joe Viola was my teacher, and he was great.” The gigs came for Sheridan, but after a few years of touring, he decided to change direction.

“The bands I worked with traveled a lot, and I got sick of being on the road,” he says. “I didn’t see that work leading to anything that I could count on for the long haul.” By coincidence, Boston happens to be the flute-making capital of the world, home to Wm. S. Haynes Flute Company, Verne Q. Powell Flutes Inc., and Brannen Brothers Flutemakers Inc. Sheridan always enjoyed music, working with his hands, and sculpting, so making flutes was a blend of all these disciplines. He worked for all three flute companies but really learned the craft of flute making during the decade he spent at Powell.

“Everything started for me there,” he says. “A Powell employee with the initiative to invest the time and effort could learn the whole process: body making, key making, head joint making, and padding and finishing. I figured I should learn it all even though I had no intention at that point of going off on my own.”

In 1982 he started Sheridan Flute Company—to this day, a one-man operation. Sheridan works out of his shops in Boston and Cologne, Germany, and produces as many as 100 head joints and two to four complete flutes annually. “The head joint is the major contributing factor to tone, dynamics, timbre, and playing in tune, and can transform an instrument,” says Sheridan. “Now people mix and match head joints and bodies; that became common practice just as I was starting out.”

After meeting German flutist Angelika Flacke in Frankfurt at a flute show, Sheridan married her and relocated to Cologne but maintained his shop in Brookline. “Boston is really the best place for me to be,” he says. I buy all my materials in the U.S. and do fabrication, turning and casting here and then import everything to Germany.”

From Germany, Sheridan ships his gold and silver head joints and flutes to Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Australia, Europe, and the U.S. Orchestral players, chamber players, jazz musicians, and amateurs play his instruments, but Sheridan doesn’t solicit professional endorsements. “I’m reluctant to ask someone if I can use their name in an ad. That was considered a no-no when I worked at Powell, and I haven’t changed my policy. Word of mouth is how people learn about my flutes—and word travels quickly.” Emmanuel Pahud, the principal flutist for the Berlin Philharmonic and internationally renowned soloist, uses a Sheridan head joint, and players in numerous European orchestras use Sheridan flutes.

Sheridan is known for his old-world craftsmanship and precise work. His flutes are noted especially for their scale and stable key design. “I make instruments that are precise and durable. Once, a French musician was playing one of my flutes with a tenor. After they took their bows, he gave her a big hug and then threw his arms back gesturing to the audience. When he did that, her flute went flying and bounced about 10 yards. The head joint was dented, but nothing happened to the body; the keys were robust enough to take it.”

Sheridan values flute construction in the old tradition and has crafted thousands of nonmechanized tools to aid his work. “I use some high-tech stuff, but it’s not cost-effective for me to invest in the machinery bigger companies use. They’re able to stamp out lip pieces quickly, whereas I spend many hours shaping each one. But I like the work. I have been able to join my interest in music and sculpting and feel I’m a pretty lucky guy.”

Mary Hurley is a grant writer in Berklee’s Office of Institutional Advancement. Adam Olenn is the website producer in Berklee’s Office of Institutional Advancement.