So You Want a BIG Publishing Deal?

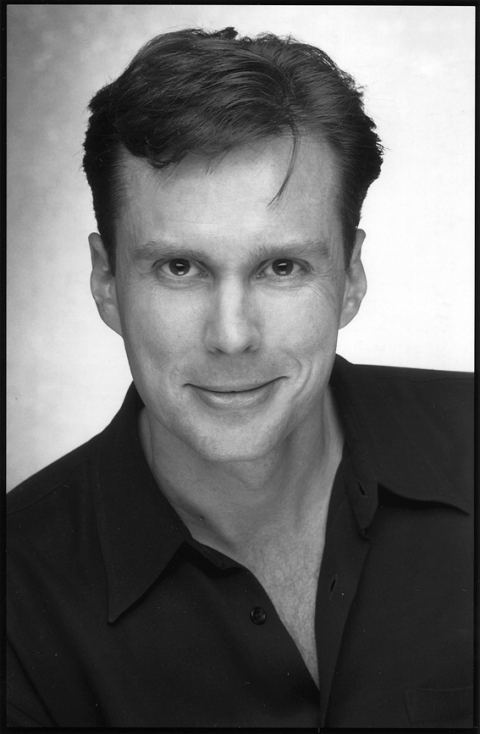

By Eric Beall '84

Eric Beall '84 is vice president of A&R at Sony Music.

So you've written a song or two, maybe even several dozen, or even hundreds, for that matter. They're all recorded on dusty work tapes stacked in your closet or on Pro Tools files eating up space on your hard drive. All these songs, carefully and lovingly created, are silently waiting on the answer to the inevitable question: What next?

The answer is a publisher. You need an effective, diligent music publisher who will share your enthusiasm for your creations; use his or her music business acumen to organize those piles of tapes into a coherent catalog; dip into a bulging Rolodex of industry contacts to put those songs into the hands of the right recording artists, music supervisors, and A&R staffers; and then, with the tenacity of a Brooklyn loan shark, will collect the inevitable flow of money that results. Simple, right?

If it's a hardworking, well-organized, well-connected music publisher that you're looking for, look no further. You already have one. In fact, he or she has been around for some time now, having been with you since you penned your first potential hit. Your publisher is your greatest untapped resource, ready to take your assets (your songs) and put them someplace where they can earn income. Whatever your publisher may lack in experience will undoubtedly be compensated for through an uncanny understanding of your work and an unquestionable devotion to your career. So, songwriter, meet your first-and quite possibly finest-publisher: you.

When an aspiring writer asks me how to find a good publisher, I usually reply, "Become one." Most successful songwriters in any large publishing company are inevitably those who have become successful music publishers on their own. They have learned by necessity how to pitch their own material, develop and administer their catalog, protect their copyrights, construct a solid business team, and establish a presence for themselves and their company in the industry. Once their publishing company has become a solid independent business entity, it presents a larger, more established music publisher with an opportunity for a real partnership, a coventure with an already productive company.

Not only are you most likely to forge an alliance with a major music publisher by becoming your own publisher, you will usually be most successful in working with big publishers once you reach the point of not really needing one. Starting your own publishing company should not be viewed as a choice to avoid affiliation with a full-service music publisher; rather, it is a proactive approach to structuring your career.

The value of taking control of your own publishing is inestimable. Once you are established, affiliating with a larger publisher amounts to one business owner seeking a coventure with another. It is understood that with an established company capable of functioning on its own, the larger company is expected to act as a business partner bringing its own expertise and adding some corporate muscle. For a large company, a coventure with such a company may be less risky than a less expensive deal with a beginning writer who hasn't learned to operate as an independent publisher. In the case of the latter, the entire burden of success lies with the bigger company.

For better or worse, the old-fashioned publishing deal in which the songwriter received the "writer's share" of all income generated from his or her song, and the publisher received the entire "publisher's share" of all income for that song, has largely disappeared. Most publishing deals today are copublishing deals, which means that the writer receives 100 percent of the writer's share of income, but also a portion (usually 50 percent) of the publisher's monies. If that seems like a better deal for the writer, it is. But it also leads back to the original paradox: to interest a big publisher, you have to become a publisher.

Most publishers would prefer to split the income and enter into a coventure with the writer's publishing company rather than keep all the publishing income but have to undertake creating a viable publishing business with a new songwriter. Why? Because they hope that the songwriter's company will bring two important qualities to the business that a larger corporate entity cannot: an intimate knowledge of the catalog (no one knows your songs better than you do) and a single-minded focus on pitching your songs (no one wants your songs placed more than you do). In that sense, the effective, independent songwriter/publisher is suited to the economic realities of most large music publishers.

You may say, "Becoming my own publisher will take time away from my writing" or "I'm not a good salesman; I'm a creative type," or "I don't have any industry contacts," or "I need advance money," or "Why should a writer sign with a larger publishing company if that writer is still expected to do all the work?"

As a music publisher who was also once a songwriter, I have used all of these objections myself. Now, after a 20-year career in this business, I offer the following response: sorry, life isn't fair, and show biz is one of the least fair sectors of life. The days of writers spending their time in solitude, quietly noodling at their pianos while a fast-talking hustler with a heart of gold peddles their songs around town, are gone-if they ever existed, that is. Read the biographies of songwriting legends such as Irving Berlin, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, or Carole King. Successful songwriters have always been aggressive about getting their songs into the right hands, managing their careers, and protecting their work. The sooner you accept these facts, the better. Smart businesspeople see the world not as it once was or as they wish it would be, but as it really is.

Truthfully, being a publisher does take time away from your writing; you'll have to work harder. Some creative people are unsuited to selling their songs, but the number is far fewer than those who believe they are unsuited to it. The publishing business is filled with former writers. Creative genes and business genes are not as mutually exclusive as many of us suppose. You will need industry contacts to be successful, so you will have to make them. You didn't have friends in high school until you went there. Similarly, you will make industry contacts when you become an active part of the industry.

And what about money? Of course you need it, we all need it. Even the big corporate publishers need it. That's why they probably won't give you any until you show that you're already earning some. And why should you do the publishers' work for them? Because you're keeping half of their money-it's a copublishing deal, remember?

If done correctly, establishing your own music publishing business requires a relatively small up-front investment and might become a long-term business from which you could quietly collect income for many years (think "Just the Way You Are" or "Misty").

What Is Music Publishing Anyway?

To many both inside and outside the music industry, music publishing is a mystery. What does a music publisher actually do? Unlike a book publisher, a music publisher doesn't really manufacture anything; the music publisher owns the rights to the song, but not the CD on which the song is sold to the consumer. The publisher's real asset is the song, not the songwriter. A publisher owns the creation, not the creator. Before you embark on the process of becoming your own music publisher, a quick overview of the business and a history lesson are in order.

In the beginning, there was the copyright. The idea of copyright law in the United States dates back to 1790 and applies to any number of media including books, photos, inventions, and songs. Copyright law dictates that if you create it, you own it-and anyone who wants to use it must gain permission from you. When a songwriter pens a song, that song (or copyright) belongs to him or her, and all rights to use the song will require the permission of and presumably financial compensation for the songwriter. This basic principle of copyright has held up pretty well since the eighteenth century, although the dawn of the Internet and the resulting file sharing have put it under fire as never before. We can only hope that it manages to hang on for at least a little while longer.

The book publishing business has a venerable history dating back to the creation of printing technology in the fifteenth century. Music publishing has its roots a bit later, around the nineteenth century, when songs began to appear for sale to consumers in the form of sheet music. Then as now, the transaction was relatively simple. In order to make his or her song commercially available to the consumer, a songwriter would assign the rights to a publisher, which would then print up the sheet music, sell it, and share the money with the songwriter.

The sheet music business continues to this day, and most of the large full-service publishers have such a division within their corporate structure. But the subject I'm addressing-contemporary music publishing-centers not around the sale of printed music, but rather on the sale or use of sound recordings. The process begins the same way: a songwriter creates a song (or copyright) and then grants the rights to a music publisher. But now, the music publisher issues a license to a record company, which allows the company to sell a sound recording of the song in return for the payment of a royalty to the publisher which then shares that income with the songwriter.

Key Questions

The first step toward becoming your own publisher is to come to grips with what will be the primary assets of your company: your songs. Whatever you've got at the moment in a drawer, on your hard drive, or on CDs or DATs is your catalog. Let's assume that you already have a sufficient number of songs to get started in this game. Ask yourself a few key questions:

Do you own the songs? If you write a song, you own its copyright, both the writer's share and the publisher's share. You are both the writer and the publisher unless you cowrote the song. If you wrote the song with someone else, you own only a portion of the song, which leads to other questions:

What percentage of the song did you write? Many songwriters assume that this is a matter of simple arithmetic: divide 100 percent of the song by the number of writers involved. So, if there are two writers, each gets 50 percent of the song; if there are three, each gets one-third. That's nice and egalitarian, but not very realistic.

Imagine that you wrote a song with the guy who owns the recording studio next door. You wrote all of the lyrics and three-quarters of the music. Your neighbor programmed the drums and contributed a chord progression that eventually became the bridge of the song.

Is he then entitled to half of the song's proceeds? Maybe. When I was a writer, I always felt that it was best to split everything equally. But many writers would disagree, particularly in an instance as one-sided as the one above. There are many factors that could figure into this calculation. Writer splits are a touchy subject, and rarely as straightforward as they might appear. The hard truth is that the percentages on a song are entirely negotiable. Have an open and frank dialogue with your cowriter(s) and reach an agreement on what percentage of the composition is owned by each writer, then get it in writing in a "split letter." This simple document outlines the basic agreement between the writers regarding the ownership of the composition. It should document the date the song was written, the writers involved, and the percentages controlled by each writer and publisher. It must be signed by each writer, and both the writers and publisher should maintain a copy on file.

If you do not have split letters for the songs in your catalog, you need to go back and create them. Yes, I'm aware that you and your cowriters are friends, and you're sure everyone will be cool if the song takes off. However, split discussions never become disputes until something good is about to happen with a song. The best time to have a discussion about percentages is before or during the writing session itself. The second-best time is immediately afterward. Keep in mind that the percentages of the publishing may also need to be negotiated with your cowriter or another publisher who may have arranged the cowriting session.

Does the song use samples? In many instances, clearing one well-known sample from a major artist can require giving up 75 percent, or sometimes 100 percent of the new copyright. Be aware that if you've stuck a big chunk of a James Brown classic into your "new" song, you own a lot less of it than you think.

Does this song sound familiar? This is every songwriter's worst nightmare. In my experience, most copyright infringement cases in the songwriting business are entirely subliminal-a matter of a writer unknowingly reprising a song lodged somewhere in his or her subconscious. In your role as publisher, try to loosen the personal attachment you have to the songs in your catalog and examine any concerns carefully. Don't fool yourself. If something sounds like it might be a problem, it probably is. Many copyright issues can be resolved through negotiation. Deal with them sooner rather than later.

Top and Middle Drawers

As a publisher, you need to gain objectivity about your catalog. Perhaps the greatest benefit to becoming your own publisher is the acquisition of some degree of objectivity about your own work and, for a few moments at least, the ability to stand on the outside of the writing process and make judgments regarding how your songs will actually function in the industry.

The catalog of any successful songwriter or publisher is a mixture of roughly 5 percent genuine, grade-A hits; 45 percent good-but-not-great songs; and 50 percent misses. If you've written 50 songs and you think you have five or 10 hits, you're fooling yourself. The goal here is objectivity.

Success in the publishing business depends largely on learning to maximize the value of not just the top 5 percent, but also the 45 percent of the songs that lie in the middle ground. As for the 50 percent of the songs that just plain miss their mark, you may not be able to do much with them, but you never know. Let's take an objective look at your catalog.

Can you spot the hits? Let's hope so. A hit song is a hard thing to define, but if nothing else, it should be obvious enough to stand out amidst the other songs in the catalog. If you're a performer, which song do you open or close with? Which one can silence a noisy audience? Which one do people request? If you had the opportunity to play one song for someone who could truly make a difference in your career, which song would you choose? These songs are your hits.

Is this a difficult choice? If it is, then chances are, you don't really have any hits in your catalog. Fine. Frankly, if you are a relatively new writer, you probably don't have a hit song in your catalog-yet. Focus instead on the three or four songs that you believe are the strongest and that best represent what you do. Those songs go in your top drawer.

Now think about the next category: the good-but-not-great songs. These songs pose the real challenge to you as a publisher. In order to have significant success, you need to learn to get the B-level songs into situations where they can generate income. They may never become hits (although with a little luck and timing, it can happen), but they can make it onto records and television shows and into advertisements. As you narrow down the songs that fit into this category, there are a few considerations:

Tempo. As a general rule, up-tempo songs are always more viable than ballads. Think about it: every album has 10 to 12 songs, out of which perhaps three or four are ballads. Every radio station plays at least three or four up-tempo songs for every ballad. Consequently, most labels release two or three up-tempo singles off any album and only one ballad. If your catalog is made up of predominantly brooding, down-tempo material, the numbers are stacked against you.

In the world of television, movies, and advertising, the advantage of up-tempo songs becomes even more pronounced. Action sequences, montages, and comedic scenes all require up-tempo material. In many instances, tempo can become the primary concern for directors and music supervisors.

In assessing your catalog, take note of all the up-tempo material. In most cases, an up-tempo song is defined not by the number of beats per minute so much as by its aggressive, rhythmic feel. Unless the song is weak, anything in this tempo category should probably go in the middle drawer.

Lyrics. Any lyric that breaks a bit from the typical love-song mold should also be a part of your active catalog. Songs with inspirational lyrics (think "From a Distance" or "I Believe I Can Fly"), controversial lyrics ("No Scrubs"), or even just silly party lyrics ("Who Let the Dogs Out"), tend to stand out in a sea of songs about broken hearts. Your catalog need some of these.

Demo quality. The production quality of a song demo is always a factor in assessing a song's value to the catalog. While you should avoid judging a song by its demo, you have to be aware that it's easier to get a cut with a record-quality demo than with a homemade piano/vocal track. When pitching songs for television projects, a great-sounding demo may be placed directly in the show. You then collect the master license fee in addition to the publishing sync fee.

The Bottom Drawer

What about those songs that haven't quite found their way into either the hit category, or the good-but-not-great category? Don't throw them out! Put them in the bottom drawer, they are part of your inactive catalog. Every writer has misses and some of the songs in this category may be the songwriter's personal favorites. To call something a miss as opposed to a hit is not an artistic judgment, it's a commercial one and publishing is a commercial business. To be effective, you need to invest your efforts in those songs most likely to yield a return.

Hope springs eternal, so as the publisher, you never throw a song away. That's a writer's role. Periodically review your bottom-drawer songs. You may find that you've judged some songs too harshly or that the musical fashion has changed and something once hopelessly dated is now back in vogue.

More important, you may find that a song in the bottom drawer is the ideal pitch for a very specialized project. I can recall pitching songs for an advertising project in which the crucial selling point was the presence of the word "smile" in the song's chorus. When you get those sorts of calls, you need all the material you can get your hands on.

Pennies from Heaven

Given the music publisher's role as a middleman in the process of turning a song into a record, music publishing exists somewhat in the shadows of the music industry. And yet, the music publishing divisions of the major music corporations are often much more profitable than their flashier, more media-friendly record label cohorts. In the fiscal year 2001–2002, EMI Music Publishing chipped in 57 percent of the parent company's total operating profit.

Sometimes ridiculed as a "pennies" business, publishing is a testament to the truth that pennies add up. If properly cared for, a classic song can continue to generate income year after year. As the number of media opportunities for music exploitation continues to increase (think about the 100 channels on your cable box and all the songs that can go on those networks), music publishing is a consistently growing business.

For a music publisher, success can be highly rewarding. Ask Berry Gordy, the legendary founder of Motown, who sold 50 percent of his publishing entity, Jobete Music, to EMI Music Publishing in 1997 for more than $132 million. Or Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss, who sold Almo/Irving/Rondor Music to Universal Music for over $250 million. These companies were started by individual entrepreneurs-songwriters who were prescient enough to be their own publisher and build those copyrights into empires. Take control of your own catalog and think big.

| Music Publishing Revenue Streams The royalty the record company pays to a publisher and then to the songwriter is the "mechanical" royalty. That money comes from the sale of discs and tapes: mechanically generated recordings. Mechanicals are the primary source of income for most writers and publishers, but not the only form of income that a publisher derives from the copyright. "Performance" royalties are payments made to the publisher by broadcasters, nightclub owners, department stores-you name it-in compensation for the licensing of public performances of the song. The songwriter receives a payment each time his or her song is played on the radio, television, in a concert hall, or even in a dentist's office. These payments are collected by the licensing organizations ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC, which then distribute the monies directly to writers and publishers based on the amount of use that any particular song has had. Performance royalties are unique in that they are the only income that flows directly to the writer without going through the hands of the publisher first. Writers and publishers receive equal royalties. So a song that generates $10,000 in royalties for the writer generates $10,000 for the publisher, but the money is distributed directly to each party by the performance rights organization. "Synchronization" fees (or sync fees) are a rapidly growing piece of the economic pie for music publishers. The term refers to music that is "synchronized" for use on television, in movies, or advertisements. Unlike mechanical royalty rates (set by the US government) or a performance royalty (an amount determined by the performance society), sync fees are negotiable. They range from nothing to the absurd. In most cases, a publisher negotiates sync fees with the film or television company, collects the money, and distributes a portion to the songwriter. Sync fees can provide a significant source of income for types of music that do not necessarily sell large numbers of records. Electronica artist Moby licensed all 18 tracks on his album Play to various advertising campaigns or movies. This exposure helped drive the album to multi-platinum status in the United States. |