Contrapuntal Improvisation

Among the many pianists who have contributed to the art of pure linear improvisation, Lennie Tristano, Dave McKenna, Alan Broadbent, Kenny Barron, and Brad Mehldau stand out for their extraordinary abilities in contrapuntal improvisation. Whether used in a solo piano, duo, or trio setting, this contrapuntal technique involves forsaking chordal accompaniment in the left hand and playing independent, moving lines instead. In the cases of Lennie Tristano and Dave McKenna, the left hand plays pure walking bass lines while the right improvises freely. Brad Mehldau’s left hand is an integral solo voice that often complements complex melodic material played by the right hand. To learn this technique and improvise up to four lines (bass line, melody, and two guide-tone accompaniment lines) between the two hands requires an oraganized approach.

Professor Neil Olmstead, an active pianist, composer, and educator, holds a bachelor’s degree from Berklee and a master’s from New England Conservatory. His book Solo Jazz Piano: The Linear Approach is available through Berklee Press.

The Concept

This approach to improvisation amazed me when, in the 1970s, I first heard Lennie Tristano’s “C Minor Complex” from The New Tristano LP. In that piece and on much of the album, Tristano’s left hand plays unrelenting, driving bass lines, while his right hand plays fascinating, complex improvisations. Later, I heard Dave McKenna’s deep, warm, swinging style on jazz standards as he played hip walking bass lines with his left hand.

I became intrigued with refining my teaching of this method of playing and introduced a Berklee course called Contrapuntal Jazz Improvisation. I have codified its principles in a book just issued by Berklee Press called Solo Jazz Piano: The Linear Approach. It examines contrapuntal improvisation beginning with very simple motives and explores motivic development, metric modulation, and multivoice improvisation.

The best way to begin learning the technique is to play left-hand motives which are worked out and memorized just as one would memorize stock chord voicings. This provides a left-hand line to play against a melody and/or improvisation.

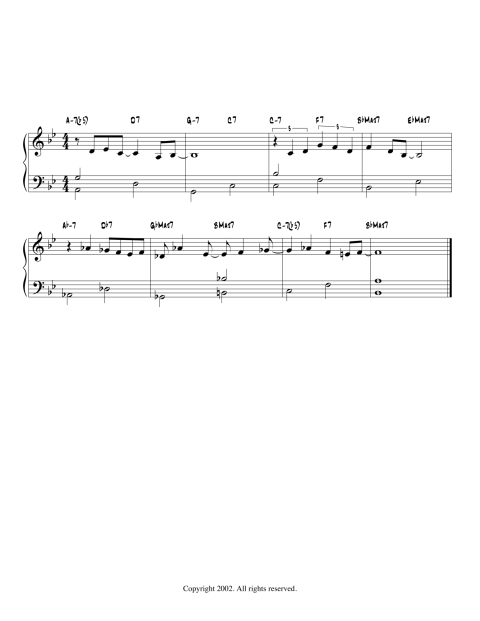

It’s easiest to start with half-note motives involving roots and fifths. In musical examples 1 and 2 (on page 21), these motives are applied to a ballad (in two) and swing (in four). As you learn the notes, you are also learning about time and groove—two integral elements of jazz.

To really get the swing feel, start working on stepwise motives in quarter notes. These, combined with the root, fifth, and chromatic approach motives provide a variety of choices for the left hand, resulting in colorful walking bass lines (see example 3).

Once some basic motives are learned for 4/4 and 3/4, explore tunes that offer possibilities of developing the bass line with pedal point, eighth-note embellishments, compound lines, and inversions. All these techniques increase the left hand’s linear vocabulary. After you gain confidence and flow in creating two-line improvisations, you’re ready to add more voices.

Multivoice improvisation

Players such as Kenny Werner, Keith Jarrett, and Brad Mehldau have a fascinating way of improvising with inner lines based on the harmony, freely improvised left-hand solo lines, and multiple voices simultaneously improvising over a standard.

When the melody is in the soprano voice and the chord roots are in the bass voice, the inner voices are often guide-tone lines drawn from the thirds and sevenths of the chords. They clearly represent the chord functions and harmonic motion, and they lead naturally by step when the chord progression goes around the circle of fifths. Playing these lines in the alto and/or tenor voices while playing bass and melody in the outer voices creates a three- or four-note linear texture. To approach this form of improvisation first requires an analysis of the harmony. It’s often easiest to sketch out your ideas first.

Begin practicing with only three voices. Play the soprano (melody) along with alto (guide-tone) line in the right hand and the bass line in the left. Next, practice melody alone in the right hand and a tenor (guide-tone) line and the bass line in the left hand to gain technical flexibility. Develop your guide-tone line ideas in examples 5 and 6.

After this, add nonchord tones to the mixture (suspensions, passing tones, appoggiaturas) to create an interesting polyphonic texture. These non-chord tones should go beyond the traditional types. In the second bar of example 7, the flat-9 of the G7 continues, being restruck on the C-7, before resolving down. At the same time, the third of the G7 holds over into the C-7. Neither of these suspensions is traditional in nature, yet they work well within a jazz context.

Melody in the Middle

Another approach to gaining control of three voices while improvising involves playing the bass with the left hand while placing the melody in a middle (alto or tenor) voice. The soprano voice then becomes a harmonic line. This upper line, mostly composed of longer note values than those of the melody, moves primarily by step throughout the phrase, sounding like an independent line in counterpoint to the melody (see example 8).

To gain further left hand flexibility, try playing the melody in example 9 down in the tenor voice with a rhythmically flexible bass accompaniment, both with the left hand, while the right hand rests. This will develop your left hand and, at the same time, free up your right to improvise above the melody line.

Next, try trading a melody line freely between voices; first in the alto, then in the tenor, and then in the soprano. Some melodies with wide ranges naturally gravitate toward other voices; however, the best tunes to start with are those with few leaps and a rather narrow melodic range. Tunes such as “I Fall in Love too Easily,” “Old Folks,” “Too Young to Go Steady,” “Everything I Love,” and “The Old Country” are good subjects.

Summary

Just as practicing bass lines strengthens your sense of time and groove, practicing melodic transposition will enhance your ability to improvise inner voices. Then, as you start embellishing melodies, your soloing ideas will grow and the freedom to improvise contrapuntally will seep into your playing. You may even find a wonderful line coming from your left hand that truly surprises you.

The point of studying this approach isn’t to sound like Tristano, McKenna, or Mehldau. It is a technique that can transform and advance your concept of jazz piano playing and lead you to new ideas. It is not an end in itself but an addition to the palettte of textural colors in your technique of solo piano playing. As Bill Evans once said of the importance of technique in music: “It should only be the funnel through which your feelings and ideas are communicated.”

Recommended Resources

Printed music: Keyboard music of J.S. Bach; Lennie Tristano, piano solo from Scene and Variations, transcription published by William H. Bauer, Inc., Albertson, NY.

Videos and books: Barry Harris, The Barry Harris Workshop Video with Workbook, Howard Rees Jazz Workshops, www.jazzworkshops.com; Solo Jazz Piano: The Linear Approach, Neil Olmstead, Berklee Press, www.berkleepress.com.

Recordings: Lennie Tristano, The New Tristano and Concert in Copenhagen; Alan Broadbent/ Gary Foster Live at Maybeck Recital Hall, vol. 14; Dave McKenna, Dancin’ in the Dark, Giant Strides, and Double Play; Brad Mehldau, Art of the Trio Vol. I, Songs, and Introducing Brad Mehldau.

Ex.1

Ex.2

Ex.3

Ex.4

EX. 5

Ex. 6

Ex. 7

Ex.8

Ex. 9