Taking on the Challenge of “Free” Music

By Peter Alhadeff ’92 and Caz McChrystal ’03

The music industry is scratching its head in what is surely one of the most confusing junctures it has faced. Bringing music to consumers suddenly has become complicated, and the old way of doing business no longer seems to be working. There also is an air of inevitability about the future because there is no foreseeable format to replace CDs and little control over CD burning and Internet piracy. The uncertain prospects of the U.S. economy and the slowdown in global trade have combined to create a “perfect storm” scenario in the industry.

The odyssey of 2001 is apparent. U.S. album sales declines were compared with the complete collapse of the French market, the fifth largest after the U.S., Japanese, British, and German markets. Worldwide shipments of CDs dropped for the first time in history. Except for music DVDs, a video medium, alternative formats fared even worse. In addition, major labels grabbed the headlines with massive layoffs and top-level personnel changes. Music executives were blamed in part for the stock-price woes of the large conglomerates they represented, and they lost internal leverage. The glamour and allure of the business in the early nineties finally ushered in a new era of retrenchment.

The irony is that the industry’s problems hardly reflect a decline in the popularity of recorded music. Rather, the industry is taking a beating largely because, despite increased usage, the commercial value of music is being heavily devalued by mass copying and piracy. Such is the concern of Jay Berman, chairman and CEO of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). According to IFPI research, 18 percent of 10,000 consumers surveyed in Germany said burning CDs resulted in their buying less music. In the United States, nearly 70 percent of those downloading music burned the songs onto a CD-R disc, and 35 percent of those downloading more than 20 songs per month admitted that they now buy less music.

File sharing and CD burning are definitely making their mark. In the United States, annual statistics are revealing. Percentage growth in CD shipments was practically non-existent in 2000, the year of Napster. In 2001, with the popularity of file sharing and CD burning on the rise, volume fell by an unprecedented 6 percent. In the same year, sales of CD singles dropped by half. In

addition, as the younger generation migrated to the Internet and used computers to burn CDs, purchases of recorded music shifted away from teenagers and toward baby-boomers. Between 1998 and 2001, the market share of the 45-plus age group rose 6 points while that of teenagers dropped 3. Record store purchases also declined proportionately against those of department stores by a considerable margin. Teenagers, once regarded as the traditional backbone of the business, were now giving their back to record companies.

Piracy and Legislation

The law is not the chaperone of the legitimate music market that it once was. Since the advent of Napster, peer-to-peer (P2P) software has become more sophisticated and technological innovation has defeated regulation. There are now 2.5 million simultaneous users of Fast Track and Gnutella, the two P2P networks that dominate illicit file sharing. That figure is nearly double

Napster’s best rating.

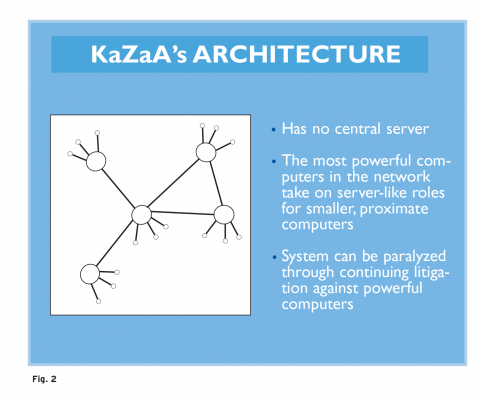

Internet antipiracy legislation was an effective tool in the days of Napster (see figs.1 and 2). Because Napster used a central server to process search requests and connect users to one another, the network could easily be shut down through legal judgment against those controlling the central server. Law enforcement in the current environment is now qualitatively more complicated. Fast Track, the software that powers KaZaA, resembles Napster in that it uses powerful computers to process individuals’ search requests. These powerful computers, or nodes, however, are not operated by the network. They belong to a vast nexus of independent users. Though lawsuits can be initiated against companies like KaZaA and damages sought, little can be done to shutter the system. By shedding their central servers, networks operating on the Fast Track architecture can only be shut down through continued litigation against traders whose computers become nodes on the network.

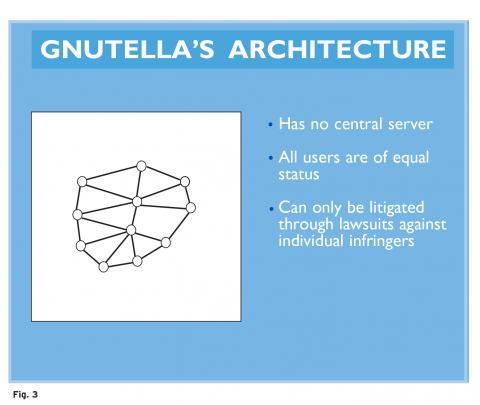

Litigation becomes nearly impossible in the completely decentralized and increasingly popular Gnutella environment. Gnutella (pronounced new-tell-ah) is an “open source” protocol (see fig. 3), that means it can be used and modified in any way that software manufacturers see fit. In practical terms, this implies that many networks powered by Gnutella exist only as chains of computers used by individual file traders without a central company to identify in a lawsuit. This decentralization is akin to a Pandora’s box: Once a network is created, it operates based on its own popularity and without a controlling hub. The only legal remedy for record labels, therefore, is to sue individual users.

The craftiness of music pirates today and the failure of legislation to stop them are best exemplified by the history of the KaZaA network. From its inception to the present, it has been the largest and most transparently profitable P2P network.

KaZaA was founded by the Dutch company KaZaABV which also created the Fast Track operating system. In February, 2002, it was sold to Sharman Networks, a media company based on the island of Vanautu off the Australian coast, after KaZaABV was named in a European lawsuit initiated by a group of record labels last year. Sharman Networks has since sought to make KaZaA profitable through an ingenious scheme. When users agree to download KaZaA, they also download Altnet, another P2P application bundled with KaZaA. Altnet is owned by Brilliant Digital Entertainment, an American company that pays Sharman a licensing fee to add the Altnet software to KaZaA incognito. The Altnet software is primarily an advertising mechanism delivering targeted pop-up ads to computers based on KaZaA search requests. Altnet also has the power to use individual computer’s untapped processing capacity and bandwidth to store and distribute content and as well as to perform complex processing tasks, chopping up complicated problems that were once only processed by extremely expensive supercomputers. Thus, Sharman Networks collects revenue from Brilliant Digital Entertainment, which in turn receives payment from advertisers and users of its data processing capability.

The controversy over the piracy of music and movies that is developing between the computer and the entertainment industries highlights the conflicting interests of two of the richest corporate sectors in America. As the Boston Globe reported on July 16, the CEOs of ten major computer companies, including Microsoft Corporation, IBM, Dell Computer Corporation, and Hewlett-Packard, replied in writing with a warning to the CEOs of the seven major entertainment companies, including Walt Disney, Viacom, News Corp., Vivendi Universal, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc., Sony Pictures Entertainment, and AOL Time Warner Inc. The music and movie industries had demanded that computer and other electronic device manufacturers add chips to block illicit copying and sharing of files; and found Congressional support through legislation proposed by U.S. Senator Ernest Hollings. The computer industry bitterly criticized any such bill on the grounds that it would place an unfair burden on itself and its consumers. Efforts to stamp out piracy of music and movies, they argued, should not be allowed to crush innovations in digital technology and networking.

Digital encryption to prevent CD burning is at present, therefore, nothing more than a piecemeal effort by labels that choose to take matters into their own hands. It is generally regarded as a weak form of protection, catching on slowly if at all.

The long-standing RIAA-sponsored Secure Digital Music Initiative (SDMI), for example, has made little impact, and Sony’s recent embarrassment with copy-protected CDs that can be decrypted by running a permanent marker around the edge of the disc have not helped. The perception persists that encryption is only useful until somebody cracks the code and makes it available via the Internet.

The Legitimate Online Market

Given the ease of piracy, through the technologies of file trading and CD burning, a huge segment of the population has come to regard recorded music as a free good. Contributing to this problem is the failure of the Internet to reach legitimate music consumers. Online music sales amounted to under 3 percent of total U.S. sales in 2001. Six out of ten Americans are able to download music with a basic computer and an Internet connection, and slightly fewer are able to burn CDs. Faced with the choice to buy or steal music on a daily basis, consumers have shied away from buying products online and have flocked to infringing file-sharing services.

To stop piracy, record companies and other online businesses must offer consumers better choices. The “bottle of wine” metaphor of intellectual-property expert John Barlow is useful in describing the choice that consumers face when obtaining music legally or otherwise. Here, the “wine” represents the music itself, regardless of its physical form. The “bottle” is the package, whether in the form of a CD, a legitimate subscription service, or a pirating service such as KaZaA. In offering compelling choices to consumers, a label “wine” must not only be a good value, but also must be offered in a quality “bottle” or delivery system that is easy to use and engaging. To date this has been a stumbling block.

Although several legitimate services went online last year, the profit record of these services is not good. The two label-backed services, MusicNet and Pressplay (joint ventures of AOL Time-Warner, BMG, and EMI, and Vivendi Universal and Sony, respectively), have created weak bottles with only a fraction of the wine one would expect. Efforts to crosslicense all of the five major labels’ catalogs to one another have so far proven fruitless and marred consumer experience with their websites. While the labels say this will be different in the near future, the reality is that collectively MusicNet and Pressplay currently make only 10 per cent of the top 100 US singles and albums available. Independent services, such as Listen.Com’s Rhapsody have not fared well either, although Rhapsody’s mid-July cross-licensing deal to stream music recorded by all five majors is perhaps a sign that times are changing.

All these services will ultimately have to match the infinite and interesting selection provided by their pirate cousins. Given that their delivery mechanisms do not operate on the P2P architecture that made infringing services attractive, this is difficult. Rather, they store everything on central servers and lack the power to connect music fans with one another on P2P networks such as Napster, an option that appeals to a new generation of music fans. Monstrous licensing and digital rights management problems need to be sorted out before P2P technology can be employed by legitimate sites. In the meantime, labels are left with outdated technology.

Labels are further hampered by questions over how portable they should make their online music offerings. Should they permit their music to be played on devices other than desktop computers, and, if so, to what extent? Pressplay, the only legitimate subscription service that allows limited CD burning, currently does so only in small numbers and for specific tracks. Yet, the expansion of the digital-music- distribution frontier will largely depend on licit services like MusicNet and Pressplay firmly embracing the unfettered use of the online music purchase.

Free Music and the Record Labels

Today, the challenge for record companies is how to vie for the patronage of music consumers in the digital domain. Free MP3s and CD burns are like manna from heaven for would-be patrons, and there is a danger that recorded music may no longer be regarded as a commodity that should return a pecuniary value. This would directly or indirectly affect a community of some 150,000 music industry professionals in the United States alone, because recorded music is the cash cow of the business. It represents twice the receipts of music-product manufacturers, five times the receipts of music publishers, and six times the receipts of the live or touring music industry. All of these ancillary sectors depend on record sales. The vibrancy and creativity of the music marketplace in this country and others cannot be expected to continue if the livelihood of music makers—not just the labels—is encumbered.

But record companies must also justify their existence in the new order. Their role cannot be in doubt. Artists have continued to sign deals with record labels because they recognize that, in the final analysis, companies have the time and skill required to manage sales of their recordings. These are resources artists themselves don’t always have, especially when there is music to write, perform, or take on the road. The division of labor between an artist and his or her label is mutually beneficial, because it is meant to maximize the distribution of musical output on the complex trading ground of modern society. The alliance may not always be harmonious, but it has endured the test of time, and it is still the preferred option of megastars with deep enough pockets to ponder alternatives.

There is little indication that the new online digital frontier is making artists hesitant to sign record deals with labels. Tensions have occasionally arisen over Internet policies of the majors, but, by and large, artists have let them get on with the business. The new Recording Artist’s Coalition, which represents emerging and established musicians, was formed in response to the threat of pro-label work-for-hire legislation. The coalition has made few pronouncements on Internet issues, and there is no indication that it objects to the way labels are managing their online operations.

Added Value

In the future, labels could direct music to consumers more adroitly in the online world than in the physical world, adding value to the music by creating a stronger relationship between the consumer and the artist. This should be a key focus of any antipiracy/free-music strategy. The majors in particular are in the best position to take advantage of a market that appears intrinsically suited to a richer listener experience—both because the well-known artists are signed to them and because they own the most sought-after sound recordings.

In turn, labels may offer artists the golden chalice of streamlined marketing and promotion. As a new generation of music consumers adjusts to buying music online, labels will have the ability to track every sale down to the individual, superseding the existing geographical boundaries that now define data-gathering systems such as the retail-oriented SoundScan and the airwaves-based Broadcast Data Systems. The invisible metadata of a web page, which helps maximize searches, can be programmed to attract more user hits and become a valuable tool for music marketers. Amazon.com, for instance, keeps a record of each consumer’s purchases and makes suggestions for future music buys. This reaches segments of the population that don’t often listen to radio or read mainstream music magazines.

This begs a question about the role of retail music sales in the future. For now, the largest component in online sales is the delivery of the physical product. But this could change if the majors embrace active subscription programs both for downloading and streaming music. Although in the short term they will not want to alienate their retail base, in the long run, file-sharing piracy will force labels to compete online and deal directly with music fans. They should thus become less reliant on retail. In the meantime, as music fans interact more with artists’ sites online, the value of an impersonal retail experience is likely to diminish further. To stay in business, retailers will have to offer a livelier buying environment like that found in the Virgin Megastore in Boston where music can be sampled online and customers are drawn in by additional features such as a coffee bar and live performances.

Revolution

A revolution is already under way in record company operations. Presently, the major labels are trying out the online market; they are learning by doing and failing. In part, this is because music has become the litmus test for survival in the digital world, and the media and entertainment conglomerates that run the business have come to rely more on technocrats in management and other alliances. Microsoft oversees the digital-rights shell of Pressplay for label giants Sony and Universal, while Warner, BMG, and EMI all rely on AOL and Real Networks for MusicNet. The new corporate culture is adjusting to a bigger challenge than simply signing the right artist.

A great deal of experimentation is happening already. Each of the majors is participating in subscription joint ventures, but several are looking independently at parallel P2P delivery solutions, and many are offering a la carte downloads directly from their websites. The bridge to the online consumer is being built on shifting ground, and the recording industry is, perforce, less linear and predictable.

The industry, moreover, cannot be expected to remain as autonomous as it was. A closer association with the public sector is inevitable. Harnessing online-delivery technologies requires lobbying the government to legislate in support of the proper infrastructure for high-speed Internet connections. Piracy needs to be neutralized; arbitrage is required to bring all concerned parties to the negotiating table to identify issues; and the rights of copyright creators, users, and content companies have to be balanced. A sign of the times is that the discussion of music issues was the most active in recent memory during the last session of Congress.

As the record companies make the shift to direct targeting of individual consumers and new communities of dedicated fans, talent should be empowered. A greater need for the continued provision of creative output may in any case change the dynamic of the artist/label relationship. Pointed sales might also reduce dependence on hit songs and be a boon to new artists. Albhy Galuten, a Berklee alumnus and vice president of advanced technology at Universal, envisions a future where musicians, even those with off-beat styles (perhaps hip-hop mambo), can secure a place in the market through an efficient, cost-effective, and more intimate distribution strategy over the Internet.

Caption: Peter Alhadeff ’92 (left) is an associate professor at Berklee and an editor for Músico Pro, an international monthly magazine serving the Hispanic music market. He earned his D.Phil. in economics and history at Oxford University. Caz McChrystal ’03 is completing his undergraduate degree studies as a music business/management major at Berklee.