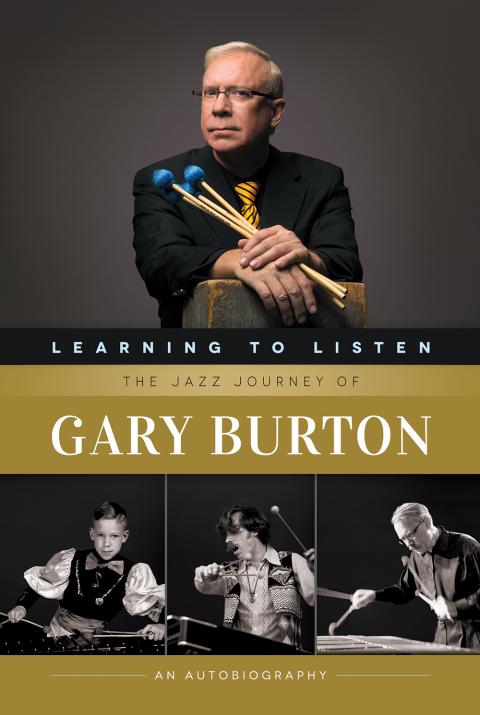

A Storied Life in Jazz

Gary Burton Book Cover

Burton’s peregrination began in rural Indiana where he began playing marimba in 1949 at the age of six. He added vibes to the mix a year later. He got a taste for the road by playing weekends around Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois with the Burton Family Band, comprising with his father (piano), sister (trombone), and brother (bass). Those gigs were primarily events at churches, Rotary and Lions clubs, Christmas parties, and the like. The family band ended around the time Burton heard his first jazz record, Benny Goodman’s “After You’ve Gone.” After he attended the Stan Kenton Stage Band Camp at 16, the die was cast. Then, a straight-A student entertaining thoughts of studying medicine or engineering, Burton describes knowing in his heart that he wanted to be a jazz musician and set his sights on Berklee.

In the summer of 1960 before entering Berklee, Burton spent a few months in Nashville where his talent impressed session guitarist Hank Garland with whom he performed regularly and appeared on Garland’s album Jazz Winds from a New Direction. Other sessions and gigs followed, and legendary country guitarist and RCA executive Chet Atkins convinced his label to offer Burton a record contract.

The following excerpt from the book picks up where Burton arrives at Berklee in the fall of 1960. The best was still to come for him as recording artist and as an educator. He devoted more than three decades to Berklee serving as a teacher and executive vice president.

Burton, now 71, has made 70 albums as a primary artist in collaboration with such names as Stan Getz, Chick Corea, Pat Metheny, Peter Erskine, Roy Haynes, Stephane Grappelli, and scores more. His output has earned him seven Grammys.Since retiring from Berklee in 2004, he has been active as a touring and recording artist.

This chapter, reminiscences from Burton’s student days, confirms that at Berklee in 1960 as today, key insights are gained both in and out of the classroom.

—Editor

This excerpt was provided courtesy of Berklee Press.

I drove into Boston during the Friday evening rush hour. I had no idea how to find Newbury Street, where the Berklee School of Music was located. In addition, this was my first encounter with big-city driving. But with a helping of beginner’s luck, I somehow ended up at the right address.

At first glance, Berklee wasn’t very impressive, and even less so after a prolonged look. It was much smaller than I expected; the entire college occupied a single brownstone. I had only seen two other colleges, each with a large sprawling campus:

The Burton Family Band (from the left): Gary, Ann, and Phil Burton circa 1955.

Indiana University in Bloomington, where I had gone to jazz camp, and North Texas State College in Denton, which my father and I had visited because it had the only other college jazz program in the country (besides Berklee). But Denton, with the occasional tumbleweed rolling down the street, was even more forlorn than Bloomington. So I chose Berklee, sight unseen, mostly out of confidence that a large city held the best opportunities. I met up with my summer jazz-camp friends from Toledo, and we found an apartment down the block from the school. The rent was $9 a week for each of us. Boston was somewhat quaint in 1960. The Back Bay area was still essentially residential, and Newbury Street—which is now the most upscale shopping area in town—consisted mostly of rooming houses. In them lived a hundred or so Berklee students, who practiced and had jam sessions at all hours. I was in heaven: it was like jazz camp, only going on year-round.

Whatever Berklee lacked in appearances, it made up for in substance. Then as now, the school hired first-rate teachers, and the small student body included wonderful musicians, many of whom went on to successful careers as players and educators. And it was all about the music—every day, as much as I could find time for. I soon realized that, being mostly self-taught, I suffered from a music-information shortage. While I could play plenty of things on my instrument I usually couldn’t explain what I was doing. But Berklee’s faculty got me caught up in short order, teaching me counterpoint, composition, harmony, arranging, the fundamentals of other instruments, and so on. I was in three different rehearsal bands, so I rarely lacked an opportunity to play.

I was disappointed at first to learn that Berklee had no vibes instructor. (The drum teacher, AlanDawson, had only recently gotten a set of vibes himself and had just started to play.) I had to choose either piano or drums as my primary instrument, though I could play vibes in the various ensembles. For one year, I took both piano and drum lessons, but soon realized I had little interest in drums. From then on, I studied piano exclusively, which proved immensely helpful to my vibraphone playing.

I studied jazz piano but also gained a great deal from a classical piano teacher, Alfred Lee. Just as I had earlier opened my ears to country music, I now found classical music to be a new source of inspiration. Alfred also taught me ear training and sight-reading. Because I had perfect pitch, I could easily play back or write down anything I heard, but he gave me exercises that raised my skills to another level. Thanks to him, I became an excellent sight-reader, which has served me well in my career.

Gary Burton in Boston 1967

My favorite teacher was trumpeter Herb Pomeroy, a Boston legend and a hero at Berklee for more than forty years. I studied improvisation with Herb and also played in the ensemble he directed. But just as important, I got to work regularly with him at The Stables, the club he operated in partnership with some other local musicians. (Its actual name was the Jazz Workshop, but since it occupied the basement room of a bar called The Stables, that’s what everyone called it.) Herb played there six nights a week. The audience comprised mostly music students and serious jazz fans, especially on the two nights a week when Herb led his big band. A lot of innovative writing and playing took place at The Stables, and I was fortunate to enjoy it on a regular basis both as a listener and as a performer.

The Stables had a relaxed and almost comical air about it, thanks to the fact that musicians ran the place. There was none of the tension that often exists between club owners and musicians. The occasional intrusion of a drunk from the upstairs bar contributed to the atmosphere. To get to the jazz club down stairs, customers had to walk through the bar and down a steep ramp to the swinging doors marking the club entrance. Unfortunately, the men’s room was halfway down that same ramp. About once a week, some lush would start down the ramp, find himself unable to negotiate the turn into the men’s room, and hurtle to the bottom, crashing through the double doors and landing in the first row of seats. It happened so frequently that after a while, the musicians barely noticed the commotion.

Those first months at Berklee were so exciting that I practically forgot everything else. I had not even bothered to call or write home to let my folks know I was okay. They didn’t want to be interfering parents, so they waited a couple of months before finally telephoning the college—just to ask if I was still there! I was called into the office and told that I ought to phone home occasionally. I felt so guilty that I started calling every week.

One night during that first winter, I got a call to rush down to Storyville, the jazz club in Boston owned by George Wein. Singer Anita O’Day was opening that night, but her band had missed their plane, and she needed a trio to back her up. I met two other students at the club and we rehearsed with her for a couple of hours to learn her music. Anita’s road manager promised us $50 each and told us to get some dinner and be back in time for the first set. We returned to discover that her musicians had managed to arrive and we wouldn’t be needed after all.

The Gary Burton Quintet in 1975. From the left: Burton, Mick Goodrick, Steve Swallow, Bob Moses, and Pat Metheny

The three of us sat through Anita’s first set, waiting for the road manager to pay us. We didn’t know if we would get the full amount or only part of it, but we had spent the afternoon rehearsing and were ready to play, so we assumed we would get something. Finally, the manager came over to offer us complimentary copies of Anita’s latest album—and that was it! No 50 bucks, not even 50 cents. I was furious but too shy to protest. We left the club and tossed the records into the first trash barrel we saw.

Years later, while reading Anita’s autobiography, I learned that during those years she was a hardcore heroin junkie, which explains her stinginess. (For a junkie, it’s mandatory to hang on to every dollar for the next score.) I also learned something else about her that explains why I never warmed to her singing.

There are two “instruments” one can play without any knowledge of music, using just intuition: drums and vocals. Any other instrument requires some knowledge of music fundamentals—such as chords, scales, how harmonies move— and most often—learning to read music. But there are quite a few drummers and singers that have had successful careers in the jazz field (and in pop and rock, certainly) simply performing by ear, without benefit of actually knowing these fundamentals. Anita was one of the ear vocalists, and finding this out helped me understand my lack of interest in her style.

Although renowned for her vocal improvising or scat singing, Anita didn’t know what was happening in the underlying compositions, and to me her choice of notes and phrases sounded like guesswork—as opposed to the great vocal scat singing of, say, Ella Fitzgerald or Sarah Vaughan, who knew the structure of the music inside out.

Also that winter, I organized my first recording session for RCA in New York. At a loss for which musicians to choose, I started by calling the only New York musicians I knew: drummer Joe Morello and bassist Joe Benjamin (both of whom I had met when we played together on Hank Garland’s album). I asked Herb Pomeroy to come down from Boston, and with Herb’s assistance I added two more New Yorkers, pianist Steve Kuhn and guitarist Jim Hall. In retrospect, it was an odd assortment of players, in terms of their different styles, but they were all excellent musicians. We gathered to record about a dozen tunes at RCA’s 23rd Street Studio in January, 1961, just one week before my eighteenth birthday.

Burton teaching at Berklee 1975

Things went wrong from the start. A major blizzard on the first day caused Morello, driving by car from New Jersey, to arrive four hours late. When he finally got there, he didn’t have any drums with him, so we got almost nothing done. The next day, Benjamin was the problem. I was going to record several familiar standards but hadn’t written out individual parts for the musicians. I assumed they would already know the tunes or could use a standard lead sheet. But Benjamin refused to play anything without a written bass part, so I had to waste valuable time scribbling bass lines for each song. When we finally did start recording, we all tried our best, but it just never came together. I was so disappointed that I asked the company to shelve it, and I’ve always been glad this was not the first record released under my name.

In the next few months, as I got more entrenched at Berklee, I began playing with an assortment of student groups that worked at clubs around town. At one of the regular places, Connolly’s—a dingy bar in Boston’s Roxbury section, a mostly black neighborhood. There I heard drummer Roy Haynes’s New York band for the first time. Roy exemplified cool. When he performed at the club, he parked his yellow convertible by the front door. He was terrific, and if you had told me then that I would be playing with him just a few years later, I’d have said you were crazy. Connolly’s often brought in solo acts and hired a local rhythm section to accompany them, and one weekend, I got a call to play with trombonist Matthew Gee. Gee wasn’t that big a name in jazz, but he had worked in the Duke Ellington band for a while, and trading on that, he had gotten a booking at Connolly’s.

Our local group (vibes, bass, and drums) arrived and set up, but when Gee got there, I could see we were in for a rough night. He was already pretty drunk before playing a note. I had worried about what tunes he would call. Would I know enough songs for him? Would he want to play standards or originals? As it turned out, my concerns were misplaced. To start the first set, Gee called for a blues in F—basic and easy. Then he suggested “Poor Butterfly,” a song so simple tha

t, although I barely knew it, we played it without a hitch. Curiously, Gee followed this with another blues in F; after that, he paused a bit and then just launched into “Poor Butterfly” again. I found this a little bizarre, but we were just getting started. For the rest of the night, he went back and forth between those same two songs, the blues in F and “Poor Butterfly,” over and over. Normally, a set would run no longer than maybe 45 or 50 minutes. After an hour and a half, as it became clear that Gee would ntinue playing these two songs indefinitely, the club owner came up and stopped us. I thought Gee might try some thing different when we began the second set, but it was right back to blues in F and “Poor Butterfly.” As the evening wore on, he got more and more wasted until he was having trouble just standing.

Burton and Roy Haynes after receiving Grammy Awards for Burton’s Like Minds album.

For my part, I was fascinated by the audience reaction to this spectacle. I was especially surprised that no one seemed to notice we were repeating the same two songs all night. I didn’t know what to make of that.

Fortunately, the crowd had thinned out by the end of the second set, when Gee finally fell completely apart. Extending his arm, he lost his grip on the trombone slide, which went sailing into the audience. Gee stared at what was now half a trombone as if he’d he had never seen such a thing, and then began to weave precariously. As he fell, he reached out to grab the vibraphone for support, managing to take my entire instrument with him

into the front row of chairs. I looked down on a tangle of resonator tubes, trombone parts, wooden folding chairs, and two customers buried in the pileup. No one was hurt and the vibes survived without major damage, but the trombone was totaled. This didn’t really matter, however, because the club owner came up to announce that we were finished for the night—and for the remainder of the weekend as well.

Despite a few of these less-than-inspiring experiences, my first year in Boston was incredibly productive. Thanks to Berklee and the Boston music scene, I was learning music as fast as I could take it in. And after I got established around Boston, I started getting occasional calls to work at a couple of local recording studios, for $10 per session. Usually these involved advertising jingles for local businesses, or background music for local singers. One time, a radio station hired me to play sound effects simulating different atmospheric conditions for the weather reports. But one session sticks out as an object lesson in jazz economics. I got a call early one Sunday morning to come right over to the studio for a session.

It was odd for a session to be scheduled early on a Sunday, and even odder to get the call only minutes in advance. In addition, this particular studio was a nuisance: it was situated up two flights of stairs, and I had to make several trips to transport my vibraphone. But $10 was a week’s rent, so I loaded up the vibes and went over. The session had already begun, and I noticed immediately that it was some kind of jazz project instead of the usual jingle session. Through the control-room window I could see my teacher Alan Dawson, the best drummer in town, along with a few other musicians I didn’t recognize. I watched for a while as I caught my breath after climbing the stairs, and I began to notice that it sounded exceptionally good.

They were playing in a less familiar key, one not so common for jazz groups of the day, which the tenor saxophonist negotiated with impressive fluency. When the tune ended, I went in to set up the vibes, and that’s when I recognized the tenor player as Paul Gonsalves, the star sax soloist with Duke Ellington’s band! I was amazed. Here was a jazz legend, recording with local players early on a Sunday morning, in a little jingle studio in Boston.

We played about a half-dozen songs that morning. I never got a copy of it, I don’t even know if it was ever released. This was the first (but hardly the last) time I would witness a major musician taking an unimportant, low-paying gig to make some needed cash. It always saddens me to think of how often it happens, how often it has to happen. In this case, the Ellington band had played a concert in town the previous night, and someone had approached Gonsalves with an offer to stay over and record the next morning, probably for a very modest payment. He had no idea which other musicians would take part or what would happen to the recording after they finished, it was just some extra spending money.

Chick Corea and Gary Burton in 2007

Sometimes, we play because we really want to play, sometimes we play as a favor for another musician, and sometimes, it’s just because we need the money. Despite countless hours of practice and concentration to elevate our art, we all too often have to put that aside because of circumstances.

Jazz has always occupied a curious middle ground between high art—the world of classical music, museums, and theater— and popular culture, which appeals to the masses. Classical music, which tastemakers hold in very high esteem, benefits from considerable financial subsidies. Pop music often fails to achieve artistic respect but makes up for that with greater commercial success. Jazz musicians live somewhere in the middle. We survive with fewer subsidies than classical musicians and less commercial success than pop stars. In the earlier days of jazz in particular, even the best-known jazz stars often lived rather modestly. The situation had improved quite a lot by the 1970s and 80s. But for many jazz musicians, life remains a daily struggle between what they believe in and what they must do to survive.