Wisdom from Sony Music Entertainment’s CEO

As given to Mark Small

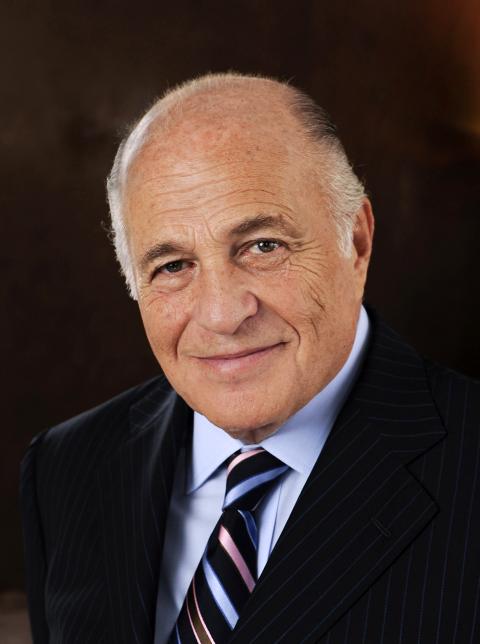

Doug Morris

Larry Busacca

Doug Morris is widely regarded as the most influential music executive in today’s industry. He has served as CEO for three major record labels: Sony Music Entertainment, where he is the current CEO, Universal Music Group (UMG), and Warner Music USA.

Morris started out as a songwriter and producer and ultimately became the president of Laurie Records before founding Big Tree Records. Atlantic Records CEO Ahmet Ertegun tapped him to run ATCO Records and later to serve as cochair and coCEO for Atlantic Records.

Throughout his spectacular career, Morris has worked with some of the most influential artists of the past five decades, including the Rolling Stones, Phil Collins, Led Zeppelin, Bette Midler, Tori Amos, INXS, Mariah Carey, Jay-Z, Stevie Wonder, and U2. Among the many notable artist deals he oversaw were the signings of Stevie Nicks and Pete Townshend to solo contracts with ATCO.

While leading UMG, Morris guided the company’s evolution from a record company to a full-fledged music entertainment company. He built UMG into an industry leader by leveraging core assets to create new revenue streams through deals with YouTube, Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Nokia, MySpace, and Last.fm, among others. He became the first media executive to monetize online music videos, essentially helping to create the music video-on-demand market online by founding VEVO. Morris’s visionary leadership and principled approach to management rank him among the greatest executives of music business.

You began your musical career as a songwriter. How did the doors start opening for you?

When I was young, I always went to the piano and played a C, F, G, chord progression and sang melodies and lyrics over it. I loved creating little songs. When I was in college—around 1958—I started interviewing with publishing companies and got a job with Lou Levy [Leeds Music Corp.] that paid $25 a week. After I got out of the Army in about 1961, I went to Robert Mellin’s publishing company and then I went to work at Laurie Records. My first semi-hit was “Are You a Boy or Are You a Girl?” which I cowrote with my brother. It was one of a string of hits for Laurie. I also cowrote and produced “Smokin’ in the Boys Room.” About two years later I started my own record company, Big Tree Records.

There were no music business programs when you attended Columbia University. How did you learn the ropes?

Having my own label taught me about the record business. That’s where I learned about how to pay salaries, the rent, and keep the door open. You learn that when you don’t have hits, you go out of business.

Was Ahmet Ertegun a mentor for you?

I met Ahmet after I’d owned my label Big Tree Records for about eight years. I’d had a lot of hit singles during that time—songs like “You Sexy Thing” [by Hot Chocolate] and “I’d Really Love to See You Tonight” [England Dan and John Ford Coley]. At some point, Ahmet asked to meet with me. He bought my label and asked me to work for him. I watched him. He was a brilliant person aesthetically and creatively. He knew how to talk to people and how to get what he wanted.

Did you have the instincts that led you to sign so many great artists throughout your career from the beginning or did your ears sharpen as you gained experience in the industry?

All of that is intuitive. A lot of people want to be a great A&R person who signs artists and puts them together with the music. Everyone thinks they know a hit record, but very few people have the instinct to understand what will work and what won’t. I didn’t know I had it when I started, but I had a lot of hits. It’s not so much ears as it is intellect and thinking about things people will like. I feel it is a given talent and if you keep up with the music and stay current, things don’t change that much.

You went out on a limb when you brought Death Row Records into the fold at Warner Music and had to stand by your conviction that rap music was going to be big.

Yes, but that wasn’t about loving rap music. It was seeing these little labels putting out rap music and how young kids were buying them. It was a different cultural moment. Seeing small labels selling them made me feel that we could sell those records at a big label. It was a business decision to see what was appealing to the young people. It’s not much different than today with Emo and dance music. You have to watch what’s going on. Young people are the trendsetters, not the music people.

You’ve been at the fore with new trends and ideas, such as monetizing online videos by establishing Vevo.

That was a logical idea. Rather than having people search through the mishmosh of user-generated videos, my idea was to take the premier videos and put them in one place. It became a big thing. As regards digital strategies and streaming services, they don’t stream music that people don’t want to hear. The key to everything is to find what people love. The whole music business is based on this one thing. People make it so much more complicated. The major labels got criticized for not being out in front with technology. But we didn’t know anything about technology back then, we understood how to make great music. Without great music, none of those surfaces work.

Is piracy still a major problem for record labels or is it abating given the alternative methods consumers have to access music?

It’s continues to be a terrible problem. It’s easy for people to steal music and have no conscience about it. Everyone steals off of YouTube. Piracy has put tens of thousands of people out of work. There used to be six major labels, now there are three in the United States. A lot of jobs were lost. [Consequently], there’s not enough money to put into developing more artists, and many have been deprived of the opportunity to be successful. It’s not a victimless crime.

I’m hoping that when streaming services become sexy enough, they will put a dent in piracy. There will be a transition and people will find streaming services easy and interesting enough to want to pay them $10 a month. It will not be a matter of character where people wake up one morning and decide that they shouldn’t steal.

What gives you the most hope for the future of the music industry?

I feel the industry is going to do better than it ever has. Over the past few years the profits in the industry have started to increase. It has to do with streaming and the record companies starting to know how to deal with the tech companies. The digital business itself is a much better business model. There’s no manufacturing and there are no returns, so the margins are much better. I think that will continue and there will be more money to invest in artists and marketing them. I think we are in for a really nice change in the atmosphere.

It’s a fascinating business and it’s important that people understand that it’s not one-dimensional. One door leads to another. That happened for me and I’ve enjoyed the whole trip. You will never get bored in this business. When you work at something you like, it’s fun. And when it’s fun, you get good at it.

What would you tell people aspiring to a career in the music industry?

I think of the kids coming out of Berklee and they have to figure out what part of the industry they love and where they’ll have a chance if they work hard. Go and do that because it will be fun. The worst that can happen is that you don’t do well, but you will have a good time. There are a lot of things to do in the music industry. You can be a producer, which requires a lot of talent, or an engineer, which is technical. You could be a songwriter or a publisher finding the people who write great songs. You could become a music publicist. There are so many different jobs that are intimately involved with the industry. When students graduate, they have to make the rounds and not become discouraged. I wish everyone good luck.