Philip Glass Shares the Stories Behind His Music

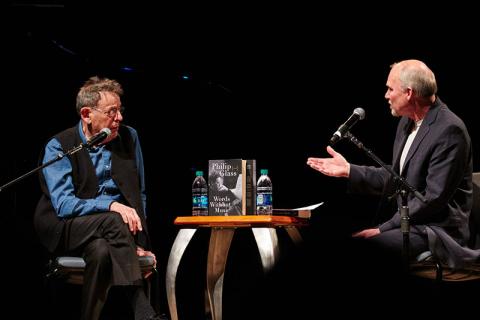

Kari Juusela, dean of Berklee’s Professional Writing and Music Technology Division, interviews Philip Glass.

Photo by Dave Green

Philip Glass talks about his unconventional career path and his musical beginnings.

Photo by Dave Green

George Lopez, artist-in-residence at Bowdoin College, performs Glass's compositions from the film, The Hours.

Photo by Dave Green

Philip Glass’s recently published memoir is titled Words Without Music. Yet in an interview at Berklee Performance Center on April 1, music permeated the famed composer’s reminiscences, his observations, and even the sound of his voice.

Glass, who has had a remarkable career of writing and performing modern music, talked with Kari Juusela, dean of Berklee’s Professional Writing and Music Technology Division, in a freewheeling conversation about the composer’s life and music. Before a packed audience, Glass—wearing a black vest and pants and chambray shirt, his froth of dark hair bobbing as he talked—described his many-faceted working life as a young man; he moved furniture, drove a crane for Bethlehem Steel, taught himself to be a plumber, worked for the artist Richard Serra, and spent long years driving a taxicab. Throughout all these jobs, Glass, as Juusela said, “changed the scope of musical composition over the last 50 years.”

However, whenever Juusela asked about the difficulty of composing such masterpieces as “Einstein on the Beach” while doing manual labor, Glass demurred. Remarkably cheerful, he insisted that in the ’60s and ’70s, it was fairly easy to make a living in New York City, and still have time to make music. He also noted that he had never been given fellowships, only received commissions for his works fairly late in his career, and has never taught, all of which he thought gave him the freedom to make music his way.

A Composer’s Beginnings

Juusela highlighted the humorous aspects of Glass’s childhood in Baltimore, which Glass talks about at the beginning of his memoir. Glass and his brother, Marty, had duties at ages 11 and 12 in the basement of their father’s music store—breaking records. The record companies had a return policy for broken 78s, he said, so the brothers were instructed to jump on the records. “We listened to a lot of them—but not the ones we broke.” To his father, music wasn’t high or low, just “music that he sold and music that he couldn’t sell,” Glass said. But to Glass, who studied the flute and then the piano as a child and went to the University of Chicago at age 15, music was an art so powerful that it eventually took over his life. “I was drawn into the world of the arts very, very young,” Glass commented, recalling hanging in the doorways of Chicago and New York clubs to listen to listen to jazz greats before he was old enough to go in.

Juusela asked him about his years studying in Paris with French composer Nadia Boulanger. “I had been at Julliard for five years,” Glass said of his decision to study with the renowned teacher in his mid 20s, “but I felt I didn’t have the technique I needed.” Her regimen was very difficult, he said. “I had to work more or less all day,” he said, “to prepare” for a class. "Madame Boulanger would ask students to play a Mozart prelude and you had to play the damn piece whether you could play it or not.” He added that she pushed him through a full course of technique in two years and that “It was really a deep immersion in music. At the end, I could visualize music. That’s when I really began to compose.”

At that time, Glass was also working with Ravi Shankar, the composer and sitar player who later influenced the Beatles. Juusela asked whether this led to Glass’s distinctive atonal style in many of his compositions. “No one asked how I did it, and I’ve never told them. This is the most I’ve ever talked about it,” he said.

Anything but Conventional

Throughout the conversation, Glass revealed his deep interest in all kinds of music, saying that he loved rock music, Shankar’s music, classical, Tibetan and African music, and has a continuing interest in a project in Mexican mountains so remote that he and the musicians communicated only through music since there was no common language, not even Spanish. “I became, I would say, addicted to these experiences.”

Juusela marveled at Glass’s performances with his Philip Glass Ensemble through the years, music “so amazingly intricate that it turns on a dime.” How, he asked, did Glass do it? “We practiced. And we performed in public,” Glass said. “You get better when you play before an audience.”

The composer’s view of music is as eclectic as his musical explorations. He values the score he composed for the film The Hours as much as his operas, music for dance, work with Paul Simon, or the tonal concertos and etudes he’s written in recent years.

Most of all, Glass confided to Juusela and the Berklee audience, he has no intention of stopping. Glass, who is 78, performs with his group about 40 times a year, and is still composing. And he’s optimistic about the musical future. There’s a good scene going on now, he said. “There’s idealism that we haven’t seen in 30 or 40 years.” The artistic life is harder now because it’s so much more expensive to live in places like New York City. But there’s hope in the innovations and explorations of young musicians and artists, Glass believes. “As a society becomes more destructive, artists become more creative.”