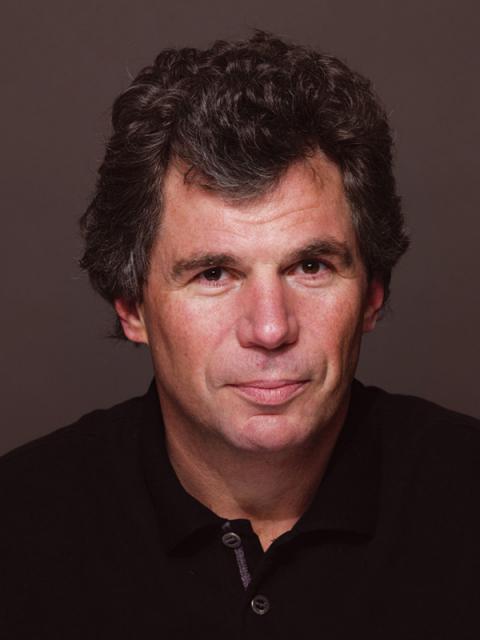

Orchestrating ‘Selma’ with Teese Gohl ‘81

Teese Gohl '81

A shot from the film 'Selma,' a 2015 Academy Award Best Picture nominee

Berklee alumnus Teese Gohl’ 81 has produced a vast body of film scores, including Academy Award winners such as Elliot Goldenthal’s score for Frida and John Corigliano’s score to The Red Violin, and has earned nominations for an Emmy and a Grammy over the course of his 25-year career. His orchestration work is now on display in Selma, the acclaimed historical drama about the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, led by Martin Luther King Jr., which spurred passage of the Voting Rights Act. The film is nominated in the Best Picture category at this year’s Academy Awards, and also drew a nomination for Best Original Song for Common and John Legend’s “Glory.”

Originally from Switzerland, Gohl, a pianist, majored in jazz composition and studied arranging, among other avenues of musical interest, at Berklee from 1977 to 1981. He went on to teach directed study courses in Berklee's Film Scoring department in the early 2000s before his film score work became too demanding to continue teaching. Gohl recently discussed his work with his alma mater, and the following is an edited and abridged version of that conversation.

Hear excerpts from the score to Selma in this trailer for the film:

What did your work on Selma entail?

“For Selma, I was called by a mutual friend to help Jason Moran, who’s not a new composer but who was a first-time film composer, to orchestrate and record the music. He was going to be traveling—he does a lot of touring—and he needed somebody to hold down the fort while he was gone. You don’t really find out what the work is until you get into it, and in this case it became more about realizing his ideas, making cues out of his compositions, and making demos, demos, demos—as well as making fixes and attending to notes from the director, the studio, and others. Once the demos were approved, I did all of the writing, with the exception of a few cues, and all of the orchestrations. The orchestra was piano, about 30 strings, a brass section, a clarinet, a bit of MIDI percussion, and a lot of live percussion. As I often do, I like to be there for the scoring, because I can really get the orchestration to come to life with the orchestra there.”

The film is very moving. Is it gratifying to play a part in bringing this important chapter in history to life on the screen?

“Of course. You know, there are very few projects that are truly gratifying. Aside from the fact that we’re doing what we love to do, this is a good artistic piece, a good cultural piece, and a good political piece that brings something to the masses that hasn’t been brought yet. It’s rare that we actually get to work on films like this. I’ve been lucky. I’ve worked on a few like that, but not many.”

You've worked on so many films. How else does Selma compare or contrast?

“The contrast is that it’s rare that a movie of this magnitude starts out as something so small. Selma started as a low-budget independent film—sort of a labor of love—and then gathered steam. Once I saw it, I cried my eyes out and thought, ‘Oh my god. What are we going to do?’ Nobody really understood the magnitude of the work we had to do, but somehow we pulled it off.”

What kinds of considerations come into play for you in getting the right sound to match the mood that the story requires?

“The first consideration is always what the director wants. What is the tone? Then you work with that in mind. I tend not to go middle of the road too often. Sometimes, if you just paint what you see, it becomes very one-dimensional. Instead, I try to paint the subtext, whether it’s the story that’s behind the scene or what’s going on in the people’s brains as opposed to what they’re saying.”

You’ve also worked for 20 years or so as Carly Simon’s music director. Can you tell me about that?

“In the late ‘80s, I was living in Boston and doing a lot of writing music and sound design at the American Repertory Theater (ART) in Cambridge. I had just met Elliot Goldenthal, who was writing the music for a mainstage production, and he hired me to play it. Carly Simon showed up on the opening night and that’s how I met her. She said she wanted me to record and about a year later I got the gig. It was a lot of studio work initially and then she decided she wanted to tour so I did all of that. It’s similar to what I’m doing now because it’s about facilitating a great artist’s ideas, dreams, and projects.”

Thinking back to your Berklee days, were there courses or professors you’ve since found to be particularly helpful in your work?

“Herb Pomeroy was a very important teacher and I always loved his class. It was top of the line in terms of jazz writing. I was lucky enough to get in there, and that’s still in me. I still hear his voice and his techniques and the whole Duke Ellington world of writing. Also, I didn’t even know I’d be involved with film scoring at the time, but Don Wilkins [former Film Scoring Department chair] was such an interesting person to know and to study with and to work with.”

Can you offer any advice to students at Berklee now studying composing, arranging, or other aspects of scoring?

“Keep doing what you’re doing. It sounds kind of bland, but it’s true. Everything changes all the time. There are still quite a few people who do original scores, but overall, it’s become so formulaic that if you want to make it, you have to fit into the formula. But I always find ways to express myself. Even in the most constrictive process, there’s always a way to break through in some way and introduce an element in music—whether it’s a melody, or an instrument, or a texture—that the person who hired you never thought of.”