Sally Taylor: The Fame Monster

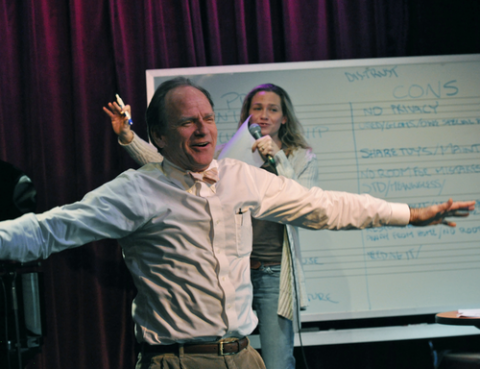

Desire for the spotlight can turn ugly—as Sally Taylor and her uncle, Berklee faculty member Livingston Taylor, demonstrate at a February clinic.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Growing up with famous parents made singer-songwriter Sally Taylor learn fame's not all it's cracked up to be.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Livingston Taylor says he admires his niece's dedication to going the independent route instead of relying on the labels who pursued her based on last name alone.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Imagine growing up famous. Your parents are world-renowned singer-songwriters. John Lennon is your next-door neighbor, and you walk to school with Paul Simon's daughter. Pretty much any aspiring musician would think that sounded pretty sweet. Sure, you fear for your parents after Lennon's death, but what's a little anxiety when record labels chase to put out your debut?

If only. At a February clinic, it didn't take much time for Sally Taylor—daughter of Carly Simon and James Taylor—to stop being polite and start getting real.

"There's sort of this mythology," she said: fame makes you happy. But that's not true. "You're not immediately afforded the luxury of never suffering again."

As she listed the perks of fame with help from the audience and her uncle, faculty member Livingston Taylor, every silver cloud had a dark lining.

Money? Bills. Influence? You're constantly signing autographs. Importance? Way to become a massive jerk. Groupies? "It's a lot more fun in fantasy than it is in reality," Livingston said, grimacing.

When Sally finally admitted she wanted to play music—not easy when your elders have accomplished so much—she tried to stay out of the spotlight. It was too soon for that kind of attention. "I didn't want to suck in public," she said.

Anyway, she hated hated record companies from the day label executive Tommy Mottola called her mom with directions on how to change her music. Ten-year-old Sally grabbed the phone and told him where he could shove it.

So Sally turned down the major labels and hit the road with her Colorado-based band, playing 200 shows a year. "I wanted to see if I could do it on my own," she said. She could, and loved it. But though the strategy protected her from embarrassment and headlines, it didn't guard against the psychological landmines.

Simply, the applause felt too good. She started wanting more approval, more gratification. Adulation is "a really, really addictive drug," Sally said, with a nasty downside: "As soon as you start believing the applause is really for you, you start believing the lack of applause is for you."

Narcissism isn't vanity, she clarified, handing out a psychological inventory: "It's the hating of yourself so much that you need the endorsement of everyone else around you."

A pretty dismal message for the eager musicians in the room. Fortunately, Sally, now married and a mother, found a way out of the dilemma. "What I think is a great idea is fame as a byproduct of success," she said. And when that happens, "I want you to be prepared with appropriate tools to protect your ego."

Her solution, drawn from a talk by hyper-successful author Elizabeth Gilbert, is to separate your art from your self-image—to think of music as something you do, not something you are. Try "thinking of yourself as a small business," Sally advised. Your artistic products are "what you are selling. But they are not you."

Livingston had a slightly different perspective. He thought the key was to achieve "good" fame, not "gratuitous" fame. "Think of someone who is famous [due to] really being of service," he said, citing musician/activist Pete Seeger. "I want people loving you because you improve the quality of their lives."

That's the way to gain respect—which includes people leaving you alone in the supermarket, as he and Sally hilariously mimed on stage.

Many students hung around after the two-hour clinic, awed by the honesty. "It's real," said fourth-semester singer-songwriter Luke Bidigare-Curtis. "All the media, Hollywood—it's all superficial."

"It was refreshing to see people of such status be, 'It's all about the music,'" said Catalina Garcia, a vocal principal.

Songwriter Emily Correia agreed. "She came from a celebrity family but she didn't choose to be a celebrity artist."

Bidigare-Curtis came away wanting to learn more about the paradox of "doing what you love but not having [it] be defined by the people who love it." Both Taylors seemed to have "done an incredible job of finding that balance," he added.

Did these ambitious musicians fully buy the negative view of fame? Sally was unsure but hopeful. "A lot of my life was revolved around keeping that mythology alive—that fame does create happiness," she said. "Somebody's got to give the other perspective."