Photographer Henry Diltz Captured the Adventure of Laurel Canyon Music in the '60s

A casual shot of Joni Mitchell in Laurel Canyon in 1970, taken a couple of months before her album "Blue" was released.

Henry Diltz

Mama Cass was "an Earth mother. She was like the Gertrude Stein of Laurel Canyon; she was always introducing people," Diltz says.

Henry Diltz

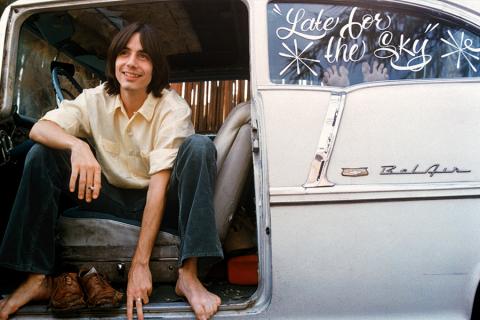

Jackson Browne told Diltz that the '60s music scene was great because it was new. "That was the thing. Singer-songwriters were a new thing," Diltz says.

Henry Diltz

David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash in Big Bear, California, in 1969

Henry Diltz

The Eagles in Joshua Tree National Park

Henry Diltz

In the middle of 1966 while on the road with his four-part harmony group, the Modern Folk Quartet, Henry Diltz popped into a second-hand store to buy a camera. He wanted to take photos of his friends back home in Los Angeles's Laurel Canyon so that they could all get together and have weekend slideshows.

With his newly acquired $20 Kodak Pony, he’d snap informal shots of his friend Joni Mitchell, a singer-songwriter from Canada, and of his pal David Crosby, who was in a young group called the Byrds, and of the Mamas & the Papas’ Cass Elliot, known to all in her circle as Mama Cass—and he wouldn’t think much of it.

“People ask me, ‘Did you realize that you were capturing history in the music industry?’ and I say, ‘Heck, no!’” says Diltz, whose body of work captures a place and time that changed popular music.

The music from this time, the 1960s and early 1970s, as well as Diltz’s photos, will be featured in the upcoming concert Great American Songbook: Tribute to Laurel Canyon at the Berklee Performance Center on February 26. Diltz will host and narrate the performance.

The event, part of the Signature Series at Berklee, will mark his seventh time back on campus.

'One by One'

“When we all lived up there, we were all musicians—I was a musician as well in the beginning—and I just remember in the middle ‘60s when your friend’s record would start getting played. I mean, I remember when ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’ started being played on the radio, and it was like, ‘Wow! There’s our pals, you know, Jim McGuinn and David Crosby, on the radio! Unbelievable!’” Diltz says. “The new sort of singer-songwriter folk rock music started happening, and one by one, people started having their songs played on the radio. One by one, people started getting famous.”

Every day was a neighborhood adventure. “The day would sort of just take off on its own. You just follow it along, and along the way you see all these friends and people, and all this stuff happens,” he says. For example, he might start the day at the Lookout Mountain Management Office, where he’d run into Graham Nash or Glenn Fry. Then, later, he’d head over to the now-legendary Troubadour Club, and all his friends would be there. One day, at a picnic at Mama Cass’s place, Joni Mitchell brought over a young English musician she had just met at a show; his name was Eric Clapton.

Joni Mitchell sings and plays the guitar in Mama Cass's backyard while David Crosby (center) and Eric Clapton (right) look on in 1968. Cass's daughter chews on one of Diltz' film containers.

An Unexpected Archive

Most of the album covers that Diltz shot—images that came to reflect the era—came not as a result of record company commissions but from friends saying, “Hey, Henry, we need some pictures for our cover,” Diltz says.

It wasn’t till the 1990s, he says, that he realized he had something of a catalog, when people started calling his body of work an archive. “I would think, ‘Wow, what does that mean? I’ve got boxes full of negatives, but I never really thought about it that way.’” Once he did start thinking about it that way, he and other rock photographers opened a showroom, the Morrison Hotel Gallery, in New York and Los Angeles. In 2016, they opened a branch in Maui, Hawaii.

Millennial Troubadours

In the early '80s, Diltz moved out of Laurel Canyon to the San Fernando Valley, and today he knows maybe one person in the canyon who’s been there since the ‘60s. These days, he says, a new generation of young musicians lives in the tucked-away cabins of Laurel Canyon. It’s an ideal place for musicians because it’s close to the clubs of Hollywood but also quiet and secluded.

“In the millennial generation, there’s a whole burgeoning music scene, and it’s almost a throwback to the ‘60s, ‘70s because there are really no more record companies anymore, so people are writing their own music, making their own albums or CDs, putting their stuff up on YouTube or whatever, and playing in these little clubs, almost like it was in the old folk music coffeehouse days,” he says.

Every now and then, a young, independent singer-songwriter will get Diltz’s name from a friend and call him up. They’ll say, hey, Henry, we need some pictures for our cover, and he’ll grab his camera and head over.