Carolyn Wilkins: Music, Mystery, and Memoir

Professor Carolyn Wilkins uncovers family history in her second book.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

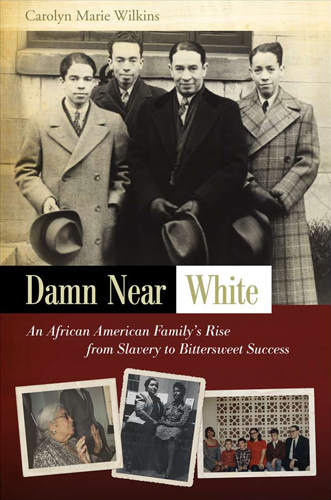

Wilkins's book delves into her family history.

Photo courtesy of University of Missouri Press

When Carolyn Wilkins is at Berklee, she's busy in the Ensemble Department—working with students, specializing in teaching small jazz bands, and often putting singers into the usual mix of piano, bass, drums, and guitar.

She also teaches ear training, basic keyboard, and a seminar called Artistry, Creativity, and Inquiry. When she's not on campus, she's an in-demand pianist and singer—working freelance, playing at churches, performing with her group SpiritJazz.

Somehow, in the middle of all of that, she found time to write her second book. Her first was music-related: Tips for Singers: Performing, Auditioning, and Rehearsing. Her newest, Damn Near White: An African American Family's Rise from Slavery to Bittersweet Success (University of Missouri Press), is about a personal search—covering her own family history, Washington politics, and a mystery.

Her main subject is her grandfather: the late J. Ernest Wilkins, assistant secretary of labor in the Eisenhower administration, the first African American to hold such a high government position. He was a brilliant, proud, and private man who resigned from his position—or was forced to resign. Wilkins wanted to know what happened and why it was never discussed.

Her research, done over three years while she continued to teach, perform, and live her everyday life as a wife and mom, introduced her to an intriguing cast of characters, including her great-grandfather John Bird Wilkins, who made his way from slavery to becoming an itinerant Baptist minister, changing his name and back story as he moved from city to city.

The family's political legacy carries on in the current generation: Wilkins's brother David is a Harvard Law professor who clerked for pioneering Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall.

"I worked on it a long time," said Wilkins, over coffee in her North Cambridge kitchen. "Then I wrote it, first as a very straightforward narrative. But my husband [jazz bassist John Voigt] was going, 'Boring.'" Voigt was the Berklee library director for 30-plus years.

So the self-described mystery "addict" made it a page-turner. . . with an answer at the end. "I enjoy reading mysteries because there's a trajectory," she said. "I realized that I could perhaps put this into a form that would make it more interesting for a person who is not a history buff, and would make it more personal."

Though she's trained as a musician, not a writer, the skills transferred to her book, she said. "I was a little insecure in my writing, so I found myself reading it out loud to see if it had a rhythm. I found that when I was really on my game or the writing was going well, it would naturally have a rhythm that was comfortable."

Asked how she actually managed to find the time to research and write the book, she again tied it to music. Wilkins started piano lessons at the age of 5, given by her musicologist mom.

"One of the great things about music study is that it teaches you discipline," she said. "Since the age of 5, no matter what else is going on in my life, I've found time to practice. There's this illusion that musicians are somehow wild and crazy. They may be in some things, but we tend to be very disciplined because that's the only way you can get it done. Another thing that music teaches you is that Rome was not built in a day. Neither is a Beethoven sonata or a Charlie Parker solo learned in a day. You take a little bit, then the next day a little bit more, but you keep your focus on the big picture over time."

Having now written one book about music and one about her family, Wilkins is gearing up to do one that will combine the two subjects, and might even fire up her composing skills.

"The next book I write will be about the musicians in my family, and that book has already kind of triggered me to write some music," she said. "It's a little closer to me. Instead of dealing with lawyers and judges, now we're talking about singers and piano players, and I feel like, 'Oh, I could write a song about this.' "