James Taylor's Truth

James Taylor spends over two hours discussing his career and creativity in Cafe 939.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Just like family holidays? Brothers Livingston and James talk shop.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

To no one's surprise, the intimate clinic draws a full house.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Livingston Taylor is clearly thrilled to have his brother at Berklee.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

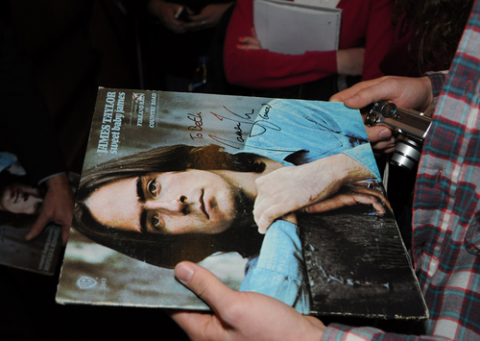

James Taylor signs a copy of his famous album <em>Sweet Baby James</em> "James Taylor (once)."

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Prospective Berklee students know the faculty is world class, boasting both Grammy winners and young guns. Still, many hope they'll meet stars so famous that even their grandparents will know who they are.

On December 3, 2008, students in Livingston Taylor's Stage Performance classes got that chance when he roped big brother James into giving a clinic at Cafe 939.

Truth be told, the singer/songwriter didn't seem to need persuading. He discussed not only his career's highlights (like recording for the Beatles' label) but also his dark times of addiction and psychiatric trouble.

And he sang—in that inimitable voice—the chorus of the first song he ever wrote:

Roll, river, roll

As long as you can be

Longest river I've ever seen

Rolling to the sea

Two hours on, he was still telling stories and hugging a guitar he bought in 1965. This is a small sampling, condensed and edited, from that conversation.

On audience interaction:

"Having prepared, you basically want to be in the moment. You want to be on the surface of yourself. . . . Yes, I do develop material to say on stage. I do repeat things: lines, one-liners, jokes, introductions. Occasionally I'll prepare something that talks about the actual town I'm playing in or the venue. What I am doing is trying to be present and share a musical experience."

Livingston Taylor, on career realities:

"James and I love to talk about show business being blue-collar work. A phrase I use is 'lots of travel, with heavy lifting at the end of the day.' This is not aristocracy. We're circus folk."

On enjoying himself:

"I never was much good at having fun. It's something that my wife regrets, that I don't have more fun. I just never was built for it, really. I don't trust it. I'd much rather be sort of working."

On coming of age during the "great folk scare" of the 1960s:

"There were a lot of coffeehouses, a lot of clubs to play. It was an easy time to get up in front of a mic and in a very modest way, in a very sustainable way, to work up your music and to get it in front of people. We benefited hugely from it being as accessible as it was. . . . I think it's a great thing that there is this community here at Berklee that basically is an open discussion and a workshop where [you] can work up your music and prepare yourself to take it out into the world. It's a great thing, Berklee is."

On leaving the South:

"Don't leave your axe in the trunk of your car in the wintertime. It will freeze."

On playing with his big band:

"It's a great community of friends, and music is spiritual food. I'm in a privileged position in my band, because we're playing my music. My approach to working with musicians is that if you want to play with these people, you should let them play. When we're all 20 we wanted to get our licks in. As time goes by you realize that you're a member of a team, and it's important to listen to the other people on stage."

On his songwriting process:

"I play guitar and musical things come out, and I trap them on a little device. Nowadays I just put 'em on a cell phone [using] voice memo."

On his repertoire:

"I've often said that I've written 18 songs a hundred times. I write a kind of traveling song—the tension between traveling for a living and trying to have roots. My father is a major character. . . . I write love songs, still, to people real and imagined. Songs are very seldom actually realistic or true or autobiographical. They are informed by my life, but they're not accurate."

On arranging:

"The fact that I started with a guitar and voice, playing my own songs, means that the guitar is the thing that informs the arrangement. My thumb basically becomes the bass part and the other things I'm playing become what you would call rhythm guitar and piano, and the vocal part expands."

On songwriting after success:

"It changes things hugely to be aware of what [fans] might expect. 99% of what we do with our conscious minds is ask, 'How'm I doing?' I try to transcend it, but I'm hopelessly committed. I want to do well. I'm not sure why. People have different definitions for success. It sounds kind of Pollyanna-ish, but the best judge of one's success is to what extent you can actually be of service. People occasionally come to me and say, 'You helped me.' That's very gratifying."