A "Marvelous" Salsero

Larry Harlow leads the show on November 18 at the Berklee Performance Center.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Student bassist Danny Torres grew up listening to Harlow's recordings on the Fania label.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

The high-energy performance had the BPC audience on its feet and dancing.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

In addition to performing in the BPC show, student Marcos Lopez accompanied Harlow at a November 16 clinic in the Berk Recital Hall.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Singer Emil Luciano

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Percussion and strings

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Faculty member Oscar Stagnaro (right) discusses the birth of salsa with Harlow in the Berk Recital Hall.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

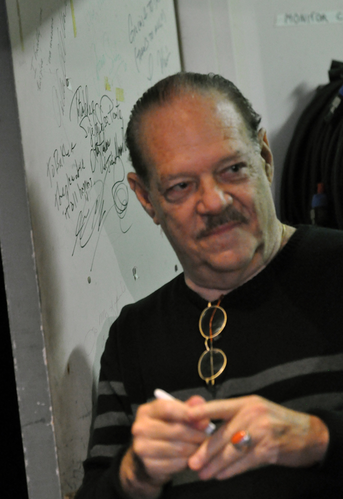

Harlow signs the Berk's backstage wall.

Photo by Phil Farnsworth

Larry Harlow, 71, is so old-school he practically founded the school—the school that salsa built.

Salsa is a hybrid of many styles of Cuban music that developed in New York and Puerto Rico in the 1960s. It matched existing rhythms with more sophisticated harmony and lyrics that were more political and conveyed what was going on in the street.

And Harlow was "a super-important person in the development of the Latin music best known as salsa. He was one of the pioneers," said faculty member Oscar Stagnaro at a November 16 clinic, part of Berklee's 12th annual Latin Music and Culture Celebration.

Harlow listened to Stagnaro's first question, then sat back. "They call me El Judio Maravilloso," he began. And he was off, launching into a sea of stories to explain "how I was transformed from this nice little Jewish kid from Brooklyn into this Afro-Cuban superstar." He paused. "Quote-unquote."

It started with a childhood "brought up in a trunk" with his vaudeville family, and listening to his dad perform on the radio under the blankets during the air raid blackouts. Then came classical piano lessons at the age of 5, watching shows in the Latin Quarter nightclub spotlight booth with a baby Barbara Walters, playing his first gig with his father at the age of 13, and falling in love with jazz.

The problem was, the jazz road closed to him. In 1952 "I went to see Art Tatum," he said. "I said to myself, If I practice every waking hour of my life, I could never play that good, ever, ever."

But he was being exposed to a path he would be able to take as his own. Not at the LaGuardia High School of Music and Art, which at the time was nearly entirely white, but the music and musicians in the five blocks between the subways and the school, then located in Harlem. "Coming out of all these mom and pop bodegas. . . they had little speakers outside and they would play—" he sang a cha-cha. The music offered the power/promise of improvisatory creativity within constraint—a simpler chord structure.

One day a fellow student asked him to join a mambo band that played stock arrangements from Cuba. He was terrible until they taught him the basics of clave rhythm. "Everything kind of started to make sense to me," he said. Every summer they'd play the hotels in the Catskills with rumba bands.

He didn't really get the picture, though, until he visited Cuba over Christmas vacation his senior year of high school. "Stepping off the plane was like stepping into paradise for me. There was a band on every corner," he said.

A few years and some failed stabs at college later, he returned, lugging a huge 70-pound 5-inch reel tape recorder, and "just went everywhere. Wherever the bands went, I went. . . and they kind of took a liking to me." He hung around the University of Havana and taped its coffee shop bands. Embarrassed by their expertise, he turned down all requests to sit in. On New Year's Eve 1958, he, like all Americans, left. "But spending that year in Havana changed my life," he said.

Back in the United States, he found his own way into the music. As with jazz, he didn't see himself in the set route. "I said, I want to do something that nobody does." Bands coming out of Cuba at the time used a variety of different orchestrations. Harlow put together a band with a unique lineup: three trumpets, two trombones, sometimes baritone and flute players, plus a rhythm section of full percussion (including timbales, congas, and bongos), keyboard, and bass.

"I kind of brought a new sound to Latin music," he said—aggressive and brassy, like Harlow himself. In 1964 he became the first artist to sign with Fania Records, and his fame began. He's since produced 300 to 400 albums, he estimated.

By the end, he wasn't Brooklynite or Jew but musician. "I got salsa-fied. I got hooked. To me it was my whole life. I made it my whole life."

He turned to Stagnaro. "Back to your question."

From there, the conversation split in countless directions, He talked about double entendres in lyrics, how he got his nickname—piggybacking on Arsenio Rodríguez, a blind Cuban composer called "El Ciego Maravilloso"—an unfortunate shortage of cowbell in one Berklee classroom, and becoming "the Rolling Stones of Latin music. We couldn't walk down the street in Caracas without getting our clothes ripped off."

He got serious. "It's a tough business to make a living at," he said—especially now that listeners are, as he put it, "bootlegging" albums left and right. "I got lucky. I was at the right place at the right time," he said. And it came after years of driving to Philadelphia with bands to make an extra few bucks at a gig, acoustic bass strapped to the roof of the car.

It took sacrifice. But 50-plus years and seven marriages later, "We're all here doing this because we love it," he said. "I say just make good music, follow your heart, practice, a lot of practice, and you'll have a great time."

Then he told a story about Tito Puente.

The clinic ended with a short piece of Latin jazz with Harlow backed by recent Berklee grad Marcos Lopez on drums, and students Danny and Marcos Torres on bass and congas, respectively. All would be in the big band that performed with Harlow at his big Berklee Performance Center show two nights later.

Harlow had, though he didn't know it, an experienced Fania backup band at the clinic. "Fania salsa—that's all my dad listened to," said Marcos Torres afterwards. "We listened to—"

"—his music all the time," his brother Danny finished.

As for Harlow's non-Latin roots, "it's not really in the blood," said Marcos. The brothers grew up in Connecticut but "you can't tell us we don't have swing."

In fact, the brothers proved they could swing along, even without a rehearsal. Harlow simply told the three students, "D minor, a change to G, and then back to D minor, 3-2 clave," Marcos said. "That's all it takes when you speak the same language."